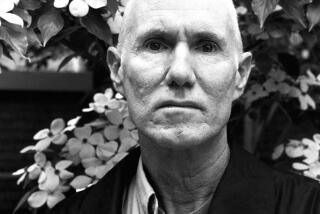

Writer A.E. Hotchner, friend to Ernest Hemingway and Paul Newman, dies at 102

A.E. Hotchner, a well-traveled author, playwright and gadabout whose street smarts and famous pals led to a loving, but litigated, memoir of Ernest Hemingway, business adventures with Paul Newman and a book about his Depression-era childhood that became a Steven Soderbergh film, died Saturday at age 102.

He died at his home in Westport, Conn., according to his son, Timothy Hotchner, who did not immediately know the cause of death.

A. E. Hotchner, known to friends as “Ed” or “Hotch,” was an impish St. Louis native and ex-marbles champ who read, wrote and hustled himself out of poverty and went on to publish more than a dozen books, befriend countless celebrities and see his play, “The White House,“ performed at the real White House for President Clinton.

He was a natural fit for Elaine’s, the former Manhattan nightspot for the famous and the near-famous, and contributed the text for “Everyone Comes to Elaine’s,” an illustrated history. Hotchner’s other works included the novel “The Man Who Lived at the Ritz,” bestselling biographies of Doris Day and Sophia Loren, and a musical, “Let ‘Em Rot!” co-written with Cy Coleman.

In his 90s, he completed an upbeat book of essays on aging, “O.J. in the Morning, G&T at Night.” When he was 100, he wrote the detective novel “The Amazing Adventures of Aaron Broom.” At 101, he adapted Hemingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea” for the stage.

He was a memorable storyteller — sometimes too memorable. Hotchner wrote an article about Elaine’s for Vanity Fair that included an anecdote about director Roman Polanski making advances on a woman on the way to the funeral of his wife, Sharon Tate, who was murdered in 1969 by Charles Manson’s followers. Polanski sued the magazine’s publisher, Conde Nast, for libel and in 2005 was awarded some $87,000, plus court costs, by a jury in London.

The son of a furrier who went broke during the Depression, Aaron Edward Hotchner was born in 1917 in St. Louis, a city he would recall with deep affection despite times so dire he claimed to have eaten paper to fight hunger. Hotchner wrote about his youth in “King of the Hill,” published in 1972 and adapted 20 years later into a Soderbergh film of the same name.

Clever and determined, Hotchner managed to land a scholarship to Washington University, where he and Tennessee Williams both worked on the school’s student magazine. Hotchner then joined the Air Force, a time he recalled good-naturedly in the memoir “The Day I Fired Alan Ladd, and Other World War II Adventures.” After the war, Hotchner settled in New York and became an editor at Cosmopolitan and worked on literary fiction.

One submission was J.D. Salinger’s “Needle on a Scratchy Phonograph Record,” a World War II story the author gave to Hotchner under the condition that nothing — not a comma — be altered. Hotchner, who had been friendly with Salinger, came through — almost. The actual story was printed intact in September 1948, but Cosmopolitan changed the title to “Blue Melody.”

Salinger never spoke to Hotchner again.

Around the same time, however, Hotchner lucked his way into literary history. Cosmopolitan wanted Hemingway to write an article about “The Future of Literature” and sent Hotchner to Cuba to track him down. So began a friendship that lasted until Hemingway’s suicide in 1961. From Spain to Idaho, they hunted, drank and attended bullfights. They lived through Hemingway’s inspiring highs and fatal lows, chronicled by Hotchner in “Papa Hemingway,” which came out in 1966 and has been translated into more than 25 languages.

But the book has a troubled history. Hemingway’s widow, Mary Hemingway, sued unsuccessfully to stop publication, alleging that Hotchner had violated the privacy of her husband and herself. She was reportedly upset that he contradicted her contention that her husband had accidentally shot himself. Critics, meanwhile, doubted the accuracy of the many long dialogues between Hotchner and Hemingway.

“Once you learn the rhythms of speech of a person, the actual words resonate with you,” Hotchner explained during a 2005 interview with the Associated Press. “I can hear him right now: ‘How do you like it now, gentlemen?’ Things he said. You’re sort of born with that, I guess, a kind of tape that runs through your head.”

Their relationship was also professional. Hotchner often served as his agent, helped edit his bullfighting book “The Dangerous Summer” and helped come up with the title for the posthumous release of Hemingway’s memoir about Paris, “A Moveable Feast.” In the 1950s and early 1960s, he adapted several Hemingway stories for television, including “The Battler,” which led to his first meeting with Paul Newman.

James Dean had agreed to star as the titular faded ex-boxer, but Newman took the role after Dean died in a car crash. Newman and Hotchner became friends, pranksters, fishing buddies, neighbors and business partners. When the actor wanted to sell his homemade salad dressing at some local shops, he called on “Hotch” to help out.

“That was just a joke,” Hotchner told the Associated Press in 2005. “It was something on the fly. ‘Let’s put up $40,000 and we’ll be businessmen.’”

Their caper turned into the multimillion-dollar Newman’s Own nonprofit empire of salad dressing, popcorn, lemonade and assorted recipes; all proceeds went to charity, notably the Hole in the Wall Gang Camp for kids with life-threatening illnesses.

After Newman’s death in 2008, Hotchner wrote about his friend in “Paul and Me.” Other projects in recent years included a collection of letters between himself and Hemingway and a reissue of his Hemingway memoir. In 2013, he was among the commentators seen in Shane Salerno’s documentary about Salinger.

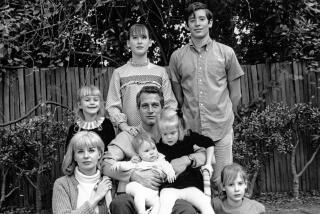

Hotchner was married three times, most recently to actress Virginia Kiser, and was the father of three children. He had numerous animals over the years, including peacocks, pedigreed chickens, and an African parrot named Ernie.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.