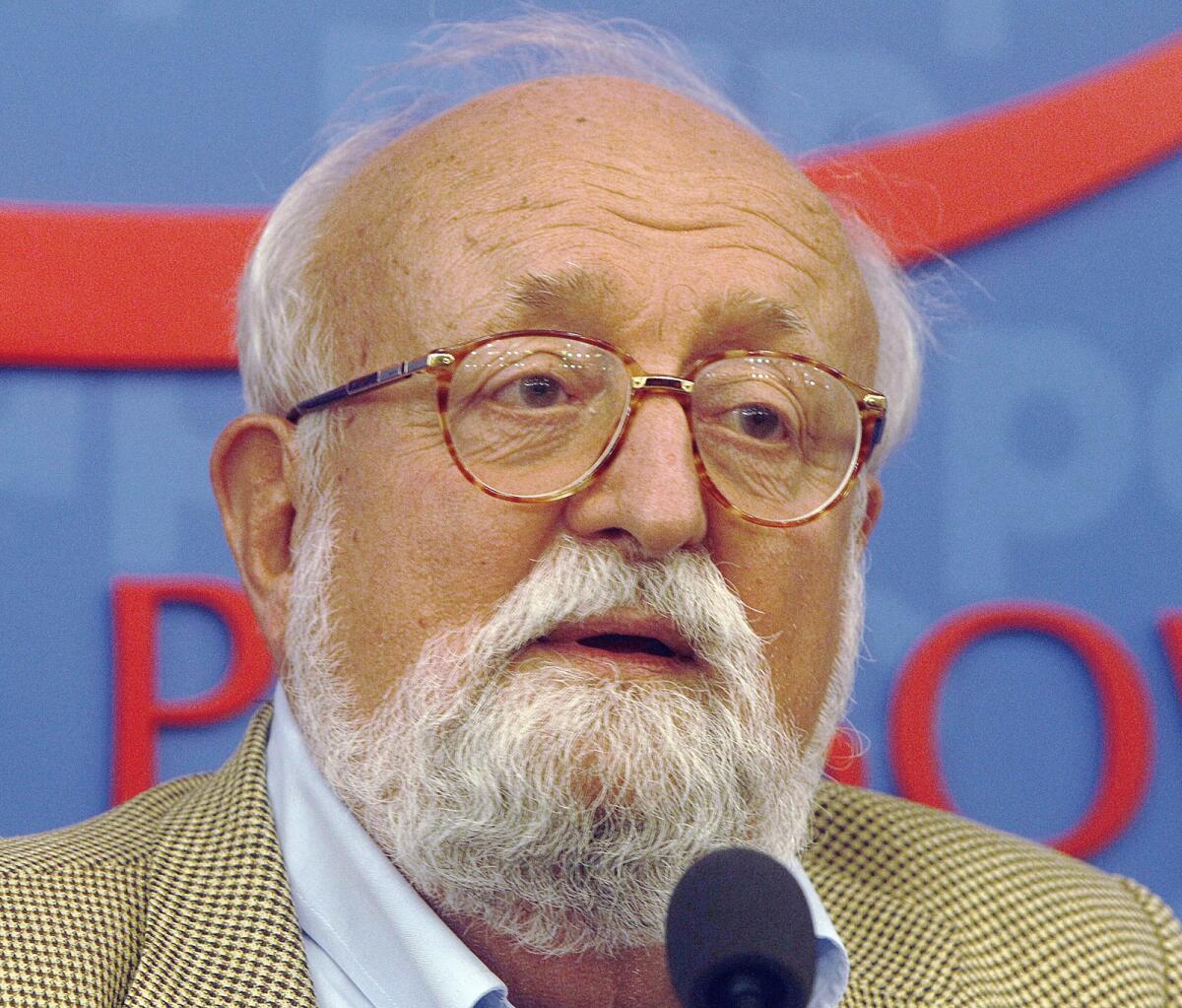

Polish composer, conductor Krzysztof Penderecki, known for monumental works, dies at 86

Krzysztof Penderecki, an award-winning conductor and one of the world’s most popular contemporary classical music composers whose works have been featured in Hollywood films like “The Shining” and “Shutter Island,” died Sunday. He was 86.

In a statement emailed to the Associated Press, the Ludwig van Beethoven Assn. said Penderecki had a “long and serious illness.” He died at his Krakow home, the Gazeta Krakowska daily said.

The statement called Penderecki a “Great Pole, an outstanding creator and a humanist” who was one of the world’s best appreciated Polish composers. The association was founded by Penderecki’s wife, Elzbieta Penderecka, and the communique was signed by its head, Andrzej Giza.

Penderecki was best known for his monumental compositions for orchestra and choir, like “St. Luke Passion” and “Seven Gates of Jerusalem,” though his range was much wider. Rock fans know him from his work with Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood.

A violinist and a committed educator, he built a music center across the road from his home in southern Poland, where young virtuosos have the chance to learn from and play with world-famous masters.

Culture Minister Piotr Glinski tweeted that “Poland’s culture has suffered a huge and irreparable loss,” and that Penderecki was the nation’s “most outstanding contemporary composer whose music could be heard around the globe, from Japan to the United States.”

“A warm and good person,” Glinski said in his tweet.

Penderecki’s international career began at age 25, when he won all three top prizes in a young composers’ competition in Warsaw in 1959 — writing one score with his right hand, one with his left and asking a friend to copy out the third score so that the handwriting wouldn’t reveal they were all by the same person.

He would go on to win many awards, including multiple Grammys, but the first prize he won was especially precious: It took him to a music course in Germany, at a time when Poland was behind the Iron Curtain and Poles couldn’t freely travel abroad.

In the late 1950s and the 1960s, Penderecki experimented with avant-garde forms and sound, technique and unconventional instruments, using magnetic tape and even typewriters. He was largely inspired by electronic instruments at the Polish Radio Experimental Studio, which opened in Warsaw in 1957 and was where he composed.

“In my works the most important is the form and it must serve the purpose,” Penderecki said in a 2015 interview for Polish state news agency PAP.

He said he begins composing with a “graphic sketch of the entire work and then I fill in the white spaces,” he said.

His 1960 “Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima” won him a UNESCO prize. Written for 52 string instruments, it can be described as a massive plaintive scream.

In the 1970s, believing that avant-garde had been explored to the full, Penderecki embarked on a new path, writing music that, to many, sounds romantic and has the traditional forms of symphonies, concertos, choral works and operas. A Catholic altar boy who grew up in a predominantly Jewish environment, he was largely inspired by religious texts: Catholic, Christian Orthodox and Jewish.

But his first opera, the 1969 “Devils of Loudun,” based on a novel by Aldous Huxley about the Inquisition, put him at odds with the Vatican, which called on him to stop the performances. He refused.

Penderecki wrote music for various historical celebrations, and conducted around the world. Among the works are the 1966 “St. Luke Passion,” commissioned by West German Radio to celebrate the 700th anniversary of the Muenster Cathedral, and the 1996 “Seven Gates of Jerusalem” to mark 3,000 years of the titular city.

In 1967 he composed a major choral work, “Dies Irae,” known also as the “Auschwitz Oratorio,” in homage to the Holocaust victims.

His second opera, “Paradise Lost,” based on the John Milton poem, seemed to reconcile him with the Catholic Church, and in 1979, he conducted a concert at the Vatican for Polish-born Pope John Paul II.

Penderecki believed that an artist is a witness of his times who reacts to it with his work and that he must also exceed boundaries and conventions to create new things. This approach often cost him, landing critical reviews.

In 1980, the leader of Poland’s Solidarity freedom movement, Lech Walesa, called him and commissioned a short piece that would honor Poles who lost their lives fighting the communist regime. Penderecki composed “Lacrimosa,” which led to the larger “Polish Requiem” that premiered in 1984 in Stuttgart, Germany.

Penderecki wrote for virtuosos and friends like violinists Isaak Stern and Anne-Sophie Mutter and cellist Mstislav Rostropovich. In 2012 he recorded an album with Greenwood, Radiohead’s guitarist.

“Because of the complexity of what’s happening — particularly in pieces such as ‘Threnody’ and ‘Polymorphia,’ and how the sounds are bouncing around the concert hall, it becomes a very beautiful experience when you’re there,” Greenwood said in a 2012 interview with the Guardian.

Penderecki said at the time that Greenwood is a “very interesting composer” and that working with the guitarist made him see his own music from a new perspective.

Greenwood tweeted Sunday to say, “What sad news to wake to. Penderecki was the greatest — a fiercely creative composer, and a gentle, warm-hearted man. My condolences to his family, and to Poland on this huge loss to the musical world.”

Penderecki’s rich, powerful, sometimes menacing music, especially in his early works, was used in Hollywood movies including Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining,” Martin Scorsese’s “Shutter Island,” David Lynch’s “Inland Empire” and William Friedkin’s “The Exorcist.”

It was also a personal matter for Penderecki to have parts of the “Polish Requiem” used in the Polish World War II movie “Katyn” by Oscar-awarded director Andrzej Wajda, about the 1940 massacre of Polish officers by the Soviets. Penderecki’s much-loved uncle was killed in that massacre.

But Penderecki said his “greatest fascination in life” was not music — it was trees. Around his manor house, he arranged a scenic arboretum featuring the various kinds of trees and plants that he brought from the most distant corners of the world where his music was played.

“It takes generations to plant a garden,” he once said. “I will do it over some 40 years, but this garden is like an unfinished symphony. Something can always be changed, you can always add new trees, find new species.”

He believed that artists are loners, and was himself a taciturn recluse. But he liked to write music on a Baltic Sea beach in Jastrzebia Gora with his close family near him.

Penderecki was born Nov. 23, 1933, in the southern Polish town of Debica. His maternal grandfather was German and his grandmother was Armenian. His father, a lawyer, loved to play the violin and instilled in his son a love of music.

Penderecki studied violin and composition at the Krakow Conservatory, where on graduation in 1958 he was appointed a professor, and next a rector. From 1972-78 he also taught at the Yale University School of Music.

Penderecki won a number of Grammy Awards during the course of his career. The Recording Academy awarded him the special merit National Trustees Award in 1968. In 1988, he won a Grammy for the recording of his 2nd Concerto for Cello, with Rostropovich. Two more came 11 years later, for his 2nd Violin Concerto, “Metamorphosen,” written for and performed by Mutter, with Penderecki conducting. Most recently, a Grammy for best choral performance came in 2017 in recognition of the “Penderecki Conducts Penderecki” album.

His other distinctions include the Best Living Composer award at the Cannes Midem Classic music event in 2000, and Poland’s highest distinction, the Order of the White Eagle, bestowed in 2005.

He is survived by his second wife, Elzbieta, who as a girl was a piano student of his first wife, Barbara, and by daughters Beata and Dominika and son Lukasz.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.