F. Lee Bailey, famed lawyer on O.J. Simpson ‘dream team,’ dies at 87

- Share via

F. Lee Bailey was at one time the most famous trial attorney in the country, known for his lightning-quick mind, relentless courtroom interrogations and insatiable self-promotion.

In trials that captivated the nation, he defended Dr. Sam Sheppard, whose story was reportedly the basis for “The Fugitive” TV series and film; Army Capt. Ernest Medina, accused of war crimes in Vietnam; confessed Boston Strangler Albert De Salvo; and newspaper heiress Patty Hearst.

“They say this is the trial of the century,” Bailey told the Los Angeles Times in 1976 during the Hearst bank robbery trial, “but it is the fourth such one for me.”

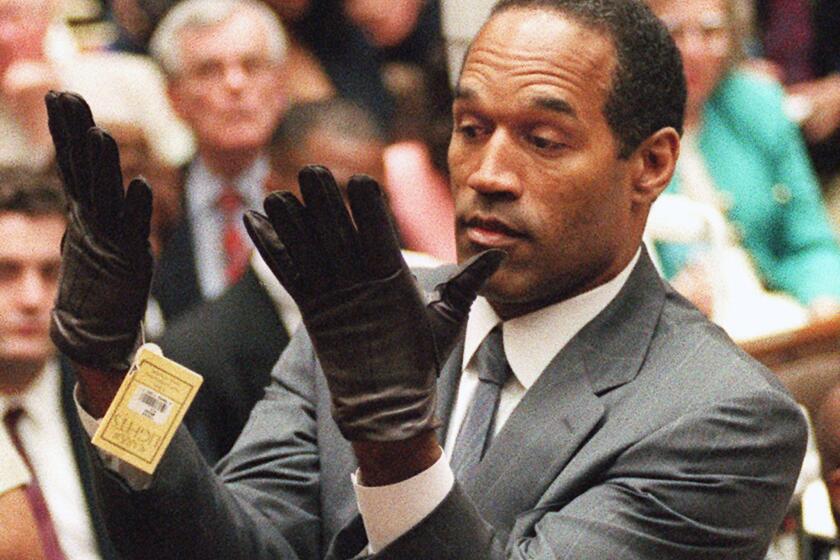

In fact, the biggest was still to come. In 1995, Bailey was part of the “dream team” of attorneys who successfully represented O.J. Simpson at his murder trial in Los Angeles, a television spectacle that was rabidly absorbed by viewers coast to coast.

The ex-football star expresses gratitude and returns to his Brentwood estate where friends and family celebrate. Relatives of the victims react with pain and grim silence to the jurors’ decision.

It was also Bailey’s last trial on a national stage. After that, when he was in a courtroom, it was most often as a defendant.

Bailey, whose fame carried on even as his career flickered out, died Thursday in Atlanta at age 87, according to the Associated Press. A cause of death was not immediately given.

The hard-charging attorney’s career was already faltering before the Simpson trial; afterward, it dropped off a cliff. He spent time in jail for defying a judge’s order, was hit with a multimillion-dollar tax judgment and filed for bankruptcy protection. The deepest blow came when he was forced to give up his license to practice law.

Broke, Bailey moved to a small town in Maine where his most prominent role was serving as a judge in a Miss Maine contest. High-profile former friends, some of whom felt injured by his past actions, disavowed him. He lived quietly in an apartment above his girlfriend’s hair salon.

But from early on Bailey made it clear that he expected to wage his battles in life as a solitary figure. He opened his 1971 bestselling book “The Defense Never Rests” with a story that took place in 1955 when he was a Marine pilot. He was flying solo in an F-86 Sabre jet off the coast of North Carolina when a red warning light flashed on in the cockpit, signaling an engine fire.

Bailey yelled “Mayday” into the radio, cut power to avoid an explosion and carefully glided the jet back to the airport for a powerless landing.

Later he learned that there was no engine fire — the warning light came on because of a short in the wiring. But no matter — it solidified his status as a lone warrior.

“If I ran a school for criminal lawyers, I would teach them all to fly,” Bailey wrote. “The ones who survived would understand the meaning of ‘alone.’”

Francis Lee Bailey Jr. was born June 10, 1933, in Waltham, Mass. His father had been in advertising but during the Depression found work with the government-sponsored WPA. His mother ran a nursery school.

Bailey’s early ambition was to be a writer. But after a couple of years at Harvard, he dropped out and joined the Navy to train as a pilot. He also read the book “The Art of Advocacy,” by prominent trial attorney Lloyd Paul Stryker. “It interested me as nothing had before,” Bailey wrote.

When he transferred to the Marines to get more jet pilot time, he requested secondary duty in the unit’s legal office, where he handled numerous military court cases. He was discharged in 1956, got his law degree from Boston University and then in 1961, only three months after being admitted to the bar, got his first major murder case.

George Edgerly had been charged with killing his wife, whose body was found headless, giving rise to Boston newspapers calling it “The Torso Murder.” Bailey had gained expertise in polygraph “lie detector” machines and was initially asked to join the defense team only to cross-examine the polygraph operator who had questioned Edgerly. But the young lawyer was so effective at undercutting the witness that he was asked to stay on and even gave the closing argument.

Edgerly was acquitted and Bailey got his first taste of fame. “The night had been a melange of television cameras and microphones,” he wrote in “The Defense Never Rests.”

Cases poured in, including that of Ohio physician Sam Sheppard, who had been in prison for 10 years after being convicted of murdering his wife.

Bailey got the decision overturned on retrial in 1966 on the grounds that the jury was exposed to highly prejudicial press reports during the initial, sensational trial that spotlighted a steamy affair the doctor was having.

It made Sheppard a free man and Bailey a national celebrity. He appeared several times on “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson” in addition to “The Dick Cavett Show,” “The David Frost Show” and “What’s My Line” as the celebrity guest. He flew private jets to Hollywood parties, hosted his own television show and landed on the covers of Time and Newsweek

In 1967 he was part of another sensational trial — of Albert DeSalvo, who had confessed to the Boston Strangler serial murders. Bailey tried a strategy aimed at getting his client committed to a mental health facility but lost that one. DeSalvo was sent to prison, where he himself was murdered in 1973.

Bailey did succeed in winning an acquittal in the 1971 court-martial marshal of Army Capt. Ernest Medina, commanding officer of the unit that committed the My Lai massacre in Vietnam, then considered the worst atrocity in U.S. military history.

Medina later went on to work for a helicopter manufacturing company controlled by Bailey. The lawyer, indulging his love of aviation, flew around the country in his own jets to handle cases or make personal appearances. He was a partner in multiple law firms and wrote more than 15 books.

“I squeeze more out of life than most people,” he said.

But there were rumblings in the legal community that Bailey was taking liberties in his quest to boost himself. In 1970, a Massachusetts judge censured him for remarks he made on “The Tonight Show,” saying the lawyer “believes that he alone should decide if special circumstances exist to justify a departure from the established norms of conduct.” In 1971, Bailey was suspended from arguing cases in New Jersey for a year.

His major troubles began in 1973, when he was indicted as an executive of a company headed by Glenn Turner, a motivational speaker who ran “Dare to Be Great” seminars and sold cosmetics in an operation prosecutors alleged was a Ponzi scheme. After a trial that ended with a hung jury in 1975, fraud charges against Bailey were dropped, but the matter reportedly put a severe crimp in his finances.

The following year came the trial of Patty Hearst, granddaughter of newspaper czar William Randolph Hearst. Hearst had been kidnapped by the radical Symbionese Liberation Army in 1974 and, after months of being held captive, seemed to join the SLA cause, even arming herself and participating in a takeover-style armed bank robbery in San Francisco.

“I had always assumed that the ’60s were the time that the country was really in crisis.

Her eventual trial was the kind of national news event that Bailey loved, but this time he lost again, and Hearst was sentenced to prison (her sentence was commuted in 1979 by Jimmy Carter and she was eventually pardoned by Bill Clinton). In her autobiography, Hearst placed much of the blame for her conviction on Bailey, saying he was incompetent.

Bailey further damaged his reputation by hosting the 1983 syndicated TV show, “Lie Detector,” in which celebrities underwent polygraph tests. In one episode, he determined that Zsa Zsa Gabor was telling the truth when she said she didn’t marry for money.

The 1995 Simpson trial was his shot at redemption. He was given the key task of cross-examining LAPD Det. Mark Fuhrman. Bailey tried to expose Fuhrman as a racist, but the witness remained stoic, insisting he had not used racial slurs, as accused.

Bailey was roundly criticized for his courtroom tactics and blustering demeanor. After Bailey failed in his attempt to expose the detective, a documentary filmmaker produced tapes of Fuhrman using racial slurs again and again. It was a key point in the long trial, but most of the credit for the Simpson acquittal went to the lead attorney, the late Johnnie L. Cochran Jr..

Bailey’s ultimate fall from grace stemmed from his defense of drug trafficker Claude Duboc, who pleaded guilty in hopes of getting a light sentence. The lawyer had been given a share of Duboc’s stock holdings worth millions. But when a Florida judge ordered the shares be turned over to the government as part of Duboc’s punishment, Bailey refused, eventually admitting he had sold some of the stock and pocketed the proceeds.

The judge sent him to prison in 1996 for six weeks for civil contempt of court.

In 2001, Bailey was disbarred in Florida over the Duboc affair and other matters, with the state’s Supreme Court citing “multiple counts of egregious misconduct, including offering false testimony.” Massachusetts followed suit, effectively ending his ability to practice law.

In 2009, he moved to Yarmouth, Maine, a small seaside village north of Portland , not far from where his family spent summers when he was a child. He lived there with his cosmetologist girlfriend in an apartment and opened a consulting business to advise clients planning to buy planes or yachts and co-authored a textbook on cross-examinations.

Bailey said he had no interest in being a lawyer again. “Been there, done that,” he told the Portland Press Herald in 2010. “I much more enjoy what I am doing now.”

But given the intoxicating heights he had reached as an attorney, it was little surprise that he wanted back into the profession.

In 2012, at 78, he passed the Maine bar exam. The state’s board of examiners, however, denied him a license, and in April 2014 the Maine Supreme Judicial Court agreed, citing the “seriousness of the misconduct that resulted in his disbarment.”

Defense attorney Alan Dershowitz said he firmly believed that his old friend was being made to suffer because of the Simpson acquittal.

“Without a doubt,” he told Town and Country magazine in 2017. “I think it was a major factor in the vindictive way in which he’s been treated.”

Bailey, though, remained pragmatic.

“I don’t see any further remedies,” he told the Bangor Daily News. “This is the end of the road.”

Bailey was married four times and divorced three. His fourth wife, Patricia, died in 1999. He had three children.

Colker is a former Times staff writer

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.