Editorial: City attorneys are responsible for protecting consumers. Give them the tools to do it

- Share via

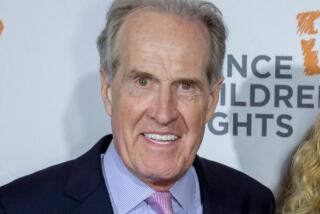

After The Times reported in 2013 that Wells Fargo stuck customers with hefty fees for accounts they never authorized, Los Angeles City Attorney Mike Feuer sued the bank.

At first, San Francisco-based Wells scoffed, claiming that L.A.’s city attorney had no jurisdiction. The bank soon learned that it was mistaken, and it settled with Feuer and two federal agencies for $185 million.

In the past, virtually any Californian would have been able to sue Wells Fargo for unlawful or fraudulent practices under state unfair competition laws. Voters sharply restricted that authority in 2004 by approving business-backed Proposition 64, but the state attorney general retained the power to sue, as did district attorneys — along with the city attorneys of Los Angeles and three other California cities with populations of more than 750,000.

But state law gave only the attorney general and district attorneys — not those four city attorneys — the ability to gather records from suspected violators before filing suit for unfair competition. That power to subpoena documents, which can be invoked only if there’s a reasonable belief that a violation has occurred, helps investigators determine whether a lawsuit is warranted. A company or other suspected violator that doesn’t want to turn over the documents can challenge the subpoena in court.

Feuer was hampered in his Wells Fargo investigation because he lacked the power to issue subpoenas.

It makes sense for the state attorney general to have pre-litigation subpoena power to enforce unfair competition laws, given that the attorney general is the state’s top law enforcement official. But the A.G. has limited resources and must leave many legitimate claims untouched. California’s 58 county district attorneys, meanwhile, seldom take on these cases. As criminal prosecutors, they are generally focused on violent crime. Unfair competition, while unlawful, is a civil matter with civil remedies and is outside the comfort zone or bandwidth of many district attorneys.

But the city attorneys in Los Angeles, San Diego, San Jose and San Francisco are exactly the right people to bring these cases. They represent hundreds of thousands of people (in L.A.’s case, millions) and are tasked with protecting consumers and enforcing civil as well as criminal laws. The Los Angeles city attorney has, for all practical purposes, the job description and duties of a state attorney general.

But not the tools. Feuer was hampered in his Wells Fargo investigation because he lacked the power to issue subpoenas. The bank continued its practices, ripping off many more customers, for three years as Feuer used more cumbersome methods to assemble his case. Fortunately, two federal agencies — the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Comptroller of the Currency — also were interested in Wells Fargo’s actions and helped the city attorney get what he needed. Had that not been the case, the bank might never have been forced to atone for, or even acknowledge, its wrongdoing.

Lawmakers have taken up a bill to correct the gap in California law that authorizes city attorneys to act while limiting their ability to do so. It ought to be an easy call. AB 814 already has passed the Assembly, and Californians would be well served if it now moves through the Senate and to the governor’s desk.

The bill is getting resistance from business groups, which claim to be comfortable with the attorney general and district attorney having pre-litigation subpoena powers but not those four city attorneys. Why not? They might not be ethical, the assertion goes, and might unnecessarily hound businesses just to make political points.

The argument is specious. The city attorneys of L.A., San Diego, San Jose and San Francisco are not small-town lawyers looking to make a buck. They are elected officials with hundreds of thousands of constituents, including the businesses within their borders, and each of them represents more people than about two-thirds of the district attorneys. Three of them have criminal as well as civil enforcement responsibilities (San Francisco’s city attorney does not).

The real objection of opponents is clear. Thirteen years ago, they rolled back California’s unfair competition laws at the ballot box by confining enforcement power to a handful of people while keeping investigatory powers from precisely those few — the city attorneys — who would be most likely to use them. They are on their guard against the kind of scrutiny and enforcement that Wells Fargo got from Feuer even without subpoenas, and worry that they might be more frequently held to account for violating the law.

But they should be held to account. City attorneys have the statutory power to do it, but they also need the tools that the attorney general and the district attorneys have. The bill would finally provide it.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.