Editorial: Ban developer contributions to City Hall

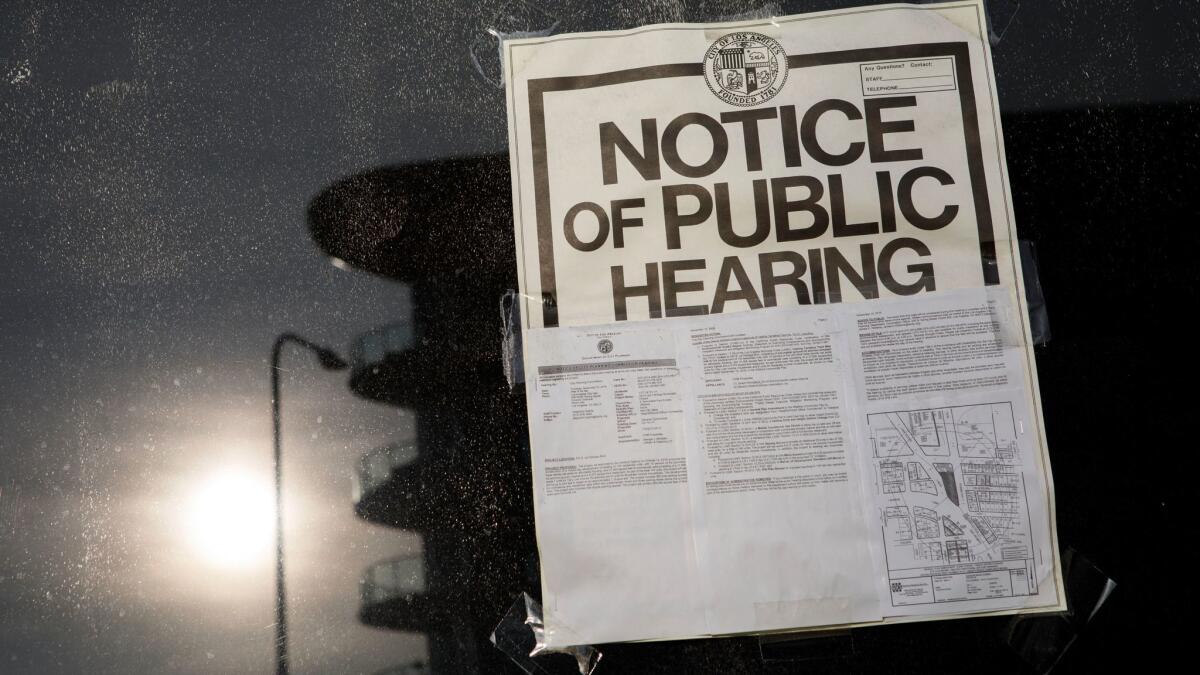

Faced with a growing distrust of the process by which the city approves new development — including widespread concern that political contributions drive land-use decisions — several Los Angeles City Council members have proposed what once seemed unthinkable: They want to ban campaign contributions from developers.

The proposal was introduced last week by Council members Paul Krekorian, Joe Buscaino, Paul Koretz, Mike Bonin and by David Ryu, who already rejects developer contributions voluntarily. It calls for the city Ethics Commission to devise an ordinance that would prohibit contributions from developers with projects currently or recently before city decision makers. The ban would apply to elected officials and candidates for city office. Or if it is determined to be illegal to ban contributions from developers (courts have equated money with speech, and have struck down broad efforts to limit contributions), the motion asks the Ethics Commission to look at other ways to limit the possibility of a quid pro quo, such as requiring elected officials to recuse themselves from a land-use decision if they have accepted donations from the developer.

Why was this once unthinkable? After all, individuals bidding on city contracts are already barred from making political contributions. But developers are different. There is a deeply embedded culture in Los Angeles City Hall in which real estate interests give heavily to local officials, presumably because they believe political contributions will buy them the zoning exemptions and other land-use decisions they want, or at least provide them with the access they need to make their best cases. Elected officials, in turn, rely on developer money for their reelection campaigns and to pay for office expenses and trips. So there’s never been the political will to turn off the contribution spigot even though it creates the appearance of pay-to-play and undermines public trust in the City Hall.

There is a deeply embedded culture in Los Angeles City Hall in which real estate interests give heavily to local officials.

Now, however, that distrust has helped propel the slow-growth Neighborhood Integrity Initiative — Measure S — onto the March ballot. The initiative would establish a two-year moratorium on developments that require exemptions from existing, though outdated, land-use rules. That would slow housing construction during a housing crisis.

The council members’ proposal is an attempt to defuse Measure S and counter the perception that city elected officials approve bad development projects because they have received campaign contributions from the developers. That perception is wrong, the council members insist, but it is persistent. Then why do bad development projects get approved?

Of course, it’s extraordinarily difficult (especially given court rulings like Citizens United and Buckley vs. Valeo) to remove money and the perception of influence from politics. Even if this law were passed, a developer who really wanted to give money to an elected official could make his contributions before filing his application with the city, or he could encourage his family and associates to contribute. Or he could spend an unlimited amount of money on his own, independent effort to get the official re-elected.

But just because it’s hard to bar developer money completely from city politics doesn’t mean city elected officials shouldn’t try. Mayor Eric Garcetti and the council have already started to modernize the outdated General Plan, which is the city’s vision for growth, and the city’s 35 community plans. With updated plans, there should be less reason to grant case-by-case exceptions to land-use rules. And by banning direct developer contributions, officials can begin, slowly, to remove the pay-to-play perception that has tainted City Hall for so many years.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.