Editorial: At 70, communist China is a rising but irresponsible global superpower

Seventy years after Mao Tse-tung proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the country once regarded as a sleeping dragon remains a conundrum. Rising rapidly among nations, it is today a strange mix of forward-looking entrepreneurialism and brutal backward repression, of private enterprise and communism, of wealth and poverty. To many Americans, the country’s aspirations remain a mystery even as it flexes its newfound muscles.

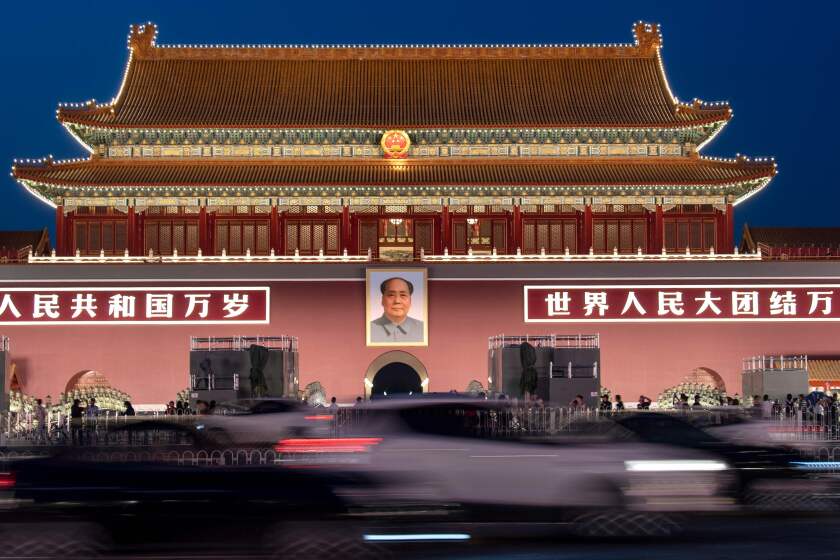

China will be spangled in red flags for its anniversary Tuesday, as it has been for several weeks, and a giant military parade will march and roll through Tiananmen Square in Beijing to showcase the country’s power and wealth. As the decades have passed, the wide-scale suffering from the early years of Mao’s leadership are beginning to fade from memory: not just the horrific man-made famines of the late 1950s that resulted in tens of millions of deaths, but also the Orwellian Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s in which as many as 2 million professors, elites, capitalists and other members of the bourgeoisie were killed. Even the one-child policy, which led to forced abortions and sterilizations, and which was replaced with a two-child policy only a few years ago, is vanishing in the rear-view mirror.

In 70 years, China’s communist state has seen a stunning economic and technological rise. It has also seen famine, massacres and harsh repression.

In the four decades since Deng Xiaoping “opened up” the country, added elements of free-market economics and created the idea of “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” China has grown wildly. Though its growth is finally cooling (while still coming in at about 6% annually), China today boasts the world’s second largest economy, with, among other things, the second-highest number of billionaires of any country. Its cities now hold tens of millions of people, its skylines include many of the tallest buildings in the world and it hosts many of the world’s largest companies. It is the world’s largest exporter of goods.

Unsurprisingly, this rising superpower expects reasonable treatment and respect from the rest of the world after years of what it perceives as foreign domination and, too often, humiliation. Among other things, China wants to hold its own with United States politically, economically, diplomatically and militarily.

But the new China also has responsibilities to meet as it rises. In part, this means addressing its share of the crisis of climate change by weaning itself faster from fossil fuels and ceasing its destructive practice of building coal-fired plants in other countries. It also means stopping its parasitic trade practices and curbing its aggressiveness in territorial disputes with its smaller neighbors.

At home, its policies have only grown more repressive in recent years. For instance, China has detained and, in some cases, tortured hundreds of thousands of Uighurs, a Muslim minority group, in reeducation camps in Xinjiang since 2016.

Current leader Xi Jinping has cracked down on dissidents, arresting many and “disappearing” others. He has purged rivals, consolidating his power in the Communist Party, and persuaded Chinese lawmakers to let him serve as president for as long as he wishes. He has moved away from reform, pushing to isolate the Chinese people from the West and the internet even as he touts the benefits of economic globalism.

The most immediate crisis is in Hong Kong, where demonstrators have been clashing with police for 17 weeks. The protests began as a challenge to an extradition law backed by Beijing, but the protesters’ demands have grown as time has passed and violence has intensified. Now, as police armed with tear gas and rubber bullets continue to face off every weekend with black-clad demonstrators in gas masks, the protesters are seeking “universal suffrage” in local elections, an inquiry into police brutality and amnesty for jailed demonstrators, among other things. Beneath those more immediate demands lies the longer term question of what is to happen to the relatively free and open territory of Hong Kong when it is fully subsumed into a repressive China in 2047.

The demonstrations are expected to heat up on Oct. 1 as the People’s Republic celebrates its birthday, and they’re not expected to die down in the coming weeks. How the central government in Beijing responds — with concessions, with force or otherwise — will give us a sense of what to expect from China in the years ahead.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.