Opinion: During Democratic debate, Warren sides with the cynics, Buttigieg is with the optimists

- Share via

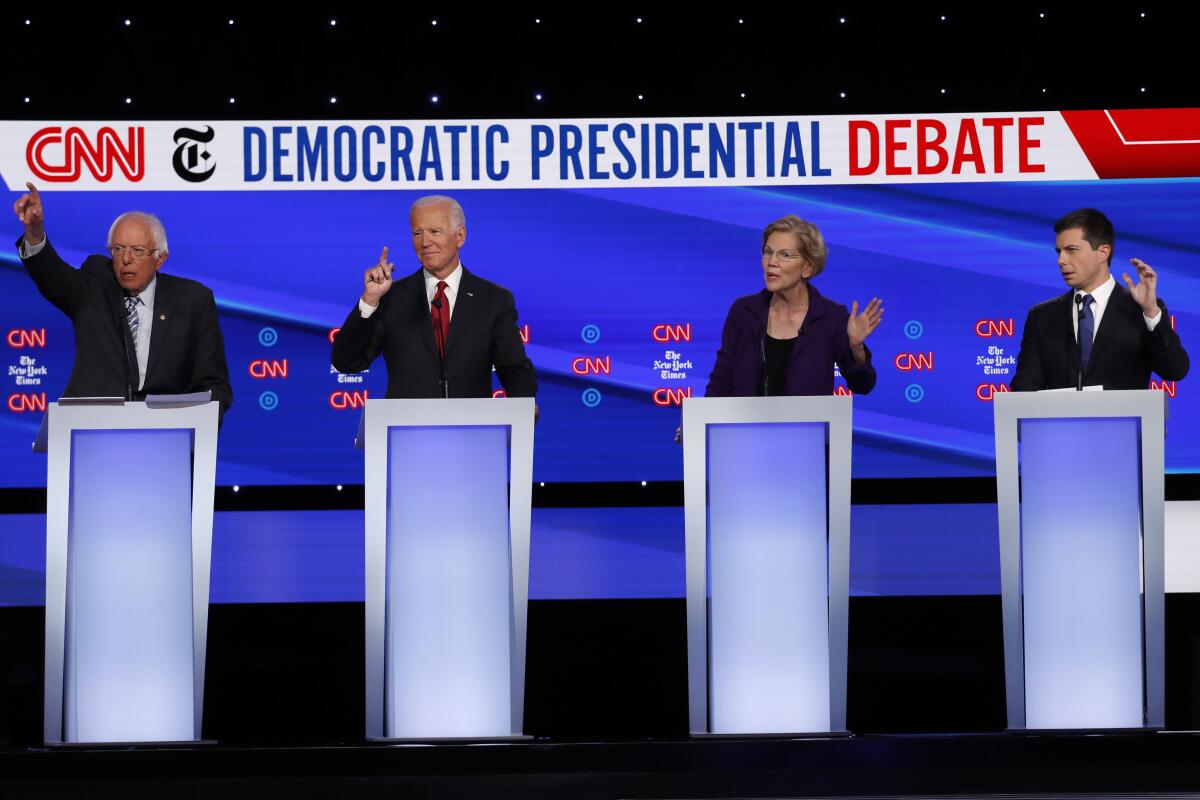

As if the differences among the top Democratic presidential contenders and President Trump weren’t stark enough, Tuesday’s debate opened with the 12 candidates on stage all holding forth on why they support the House impeachment inquiry and, in many cases, Trump’s removal from office.

Yet the Democrats know that if they win the nomination, they’ll face the same set of voters that Trump will in November 2020, assuming he’s not actually forced from office and abandoned by the Republican Party — an extremely safe assumption at this point. And some of those candidates are pushing the same emotional buttons Trump pushed in 2016 and continues to push today.

No, I’m not suggesting that any of the Democrats are making overt or even subtle appeals to xenophobes and nationalists. They’re not being that ugly. But just as Trump argued that voters were being ignored or even abused by a powerful, shadowy force that controlled the government — variously referred to as “the Washington elites,” “the swamp” and, more recently, “the Deep State” — a number of Democrats are trotting out their own version of a powerful, shadowy force that’s harming ordinary Americans: corporations and wealthy individuals whose lobbyists and campaign donations have put the federal government on a leash.

Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) are the foremost exponents of this point of view, along with billionaire Tom Steyer, who put it succinctly when talking about income inequality. Pointing to the decline of organized labor and how companies’ earnings aren’t being fairly shared with their employees, Steyer said, “There’s something wrong here, and that is that the corporations have bought our government.”

There were plenty of references to corporate greed and a lack of accountability from moderates as well as liberals on stage. But Sanders, Warren and Steyer went furthest by portraying corporations and wealthy individuals as actually controlling the levers of government, corrupting it and running roughshod over the population. This echoes Trump’s contention in the 2016 campaign that key segments of the population, such as coal miners and auto workers, had been sold out or forgotten by Washington.

For example, Warren said the real blame for manufacturing job losses wasn’t automation, as entrepreneur-turned-candidate Andrew Yang argues. Instead, she said, it was bad trade policies dictated by “giant multinational corporations who’ve been calling the shots on trade, giant multinational corporations that have no loyalty to America.”

Similarly, on the income gap in America, Warren said: “[T]he truth is, we cannot afford to continue this level of income and wealth inequality. And we cannot afford a billionaire class, whose greed and corruption has been at war with the working families of this country for 45 years.”

Sanders neatly summarized the us-versus-corporate-them mentality in his final comment of the evening. “There is no job that I would undertake with more passion,” he said in his characteristically impassioned way, “than bringing our people together around an agenda that works for every man, woman, and child in this country rather than the corporate elite and the one percent.”

It’s par for the course that, when facing an incumbent in the White House, challengers accentuate the negative. Otherwise, they’re not giving the public much reason to vote for change. Still, several of the more moderate Democrats are painting a decidedly less cynical and more hopeful picture for voters. Their argument, in essence, is that the system isn’t bad — its leader is.

Sens. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) and Cory Booker (D-N.J.), South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg and former Vice President Joe Biden were the most forceful exponents of this point of view Tuesday. They contended that the country is poised to make progress on numerous fronts, including healthcare and gun violence, because most Americans agree on the path forward. Rather than holding out for more dramatic and disruptive solutions, they argued, Democrats should seize the opportunity that’s in front of them.

For example, when asked about having the government buy back the millions of assault weapons now owned by Americans (an idea championed by former Rep. Beto O’Rourke), Buttigieg said, “On guns, we are this close to an assault weapons ban. That would be huge. And we’re going to get wrapped around the axle in a debate over whether it’s ‘hell, yes, we’re going to take your guns’?”

Klobuchar sounded a similar note. “The public is with us on this in a big way,” she said when asked about mandatory gun buybacks. “The majority of Trump voters want to see universal background checks right now. The majority of hunters want to see us move forward with gun safety legislation. There are three bills right now on Mitch McConnell’s desk, the background check bill, my bill to close the boyfriend loophole so domestic abusers don’t get guns, the bill to make it easier for police to vet people before they get a gun. That’s what we should be focusing on.”

Warren responded by saying that the system is too rigged to allow progress, so it must be smashed: “You say we’re so close. We have been so close. I stood in the United States Senate in 2013, when 54 senators voted in favor of gun legislation and it didn’t pass because of the filibuster. We have got to attack the corruption and repeal the filibuster or the gun industry will always have a veto over what happens.”

Some people would argue — OK, I would argue — that the filibuster isn’t an enabler of corrupt forces, it’s a blunt instrument wielded by minority parties to block changes that are unilateral and lack broad support. It’s been wielded far too often in the last decade, that’s for certain. But it’s been a shield against bad policies as much as an obstacle to good ones.

But I digress. It’s conventional wisdom in politics that people don’t want to vote for a buzzkill candidate, they want to vote for one with a hopeful message. Even Trump, with all his appeals to fear and distrust, still emphasized a hopeful vision of boom times to come. The issue for Democrats is whether their potential nominees are peddling a vision that’s so cynical about the present that it leaves no room for optimism about the future.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.