Op-Ed: Why is California’s age-based COVID-19 vaccine policy overlooking disabled people like me?

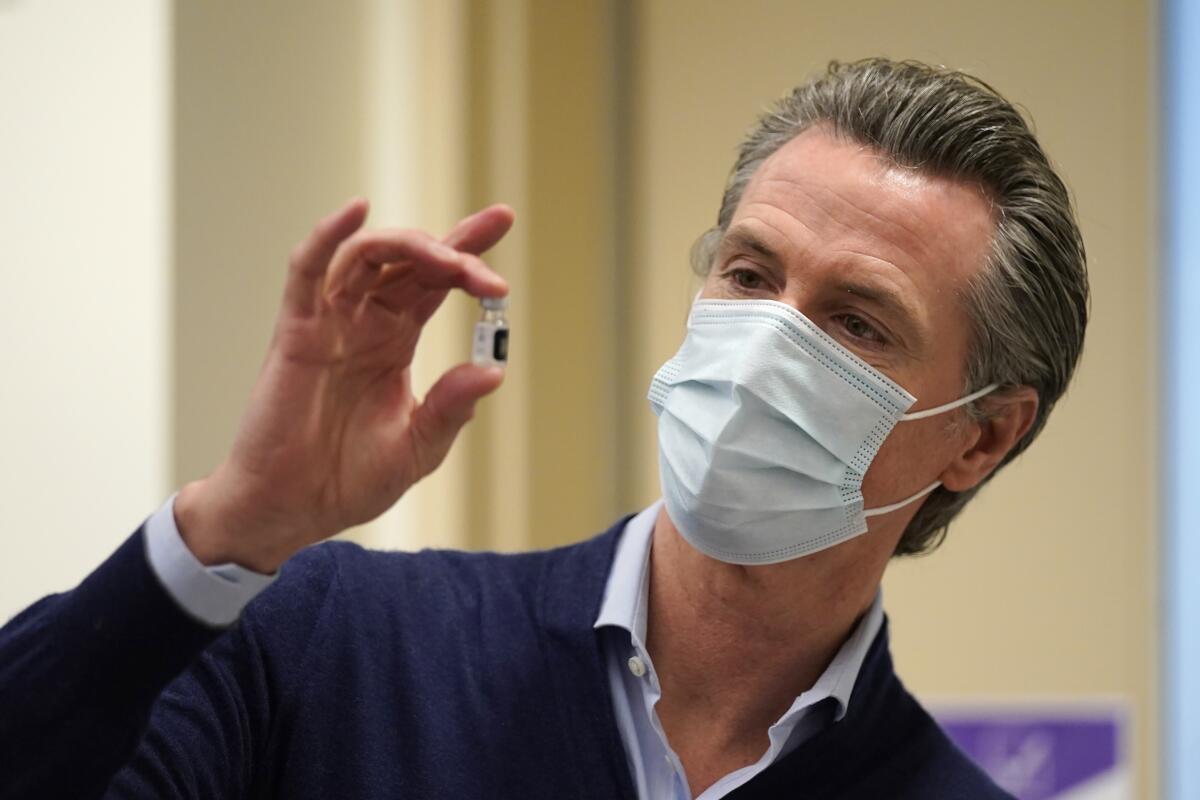

When Gov. Gavin Newsom announced the latest changes in the way California determines eligibility for COVID-19 vaccines, he chose an analogy that unintentionally revealed just how misguided the revised guidelines are.

It’s like boarding an airplane, Newsom said. The gate agents don’t wait for every first-class passenger to enter the plane before they let the business-class passengers on. And the customers traveling in economy don’t wait until every last business-class passenger boards before they head down the jetway.

The problem? The governor failed to include those who usually get to board the plane first: people with disabilities. Like me.

Unfortunately, that oversight is hardly surprising. Since the pandemic started, we have been largely confined to our homes without the support we are used to. Quarantine means many of our caregivers stayed away, causing our family members to quit their jobs so they could fill in. Many students with disabilities aren’t receiving the support they need to properly attend, and benefit from, virtual school. We feel so alone.

But now Newsom appears to have downgraded us — or overlooked us — in his vaccine distribution plan, which first gave priority to people by occupation and then by age. Neither approach accounts for the needs of the millions of Californians with disabilities.

I have cerebral palsy, use a wheelchair and communicate by typing on my iPad with my toes. Why would a healthy 50-something (albeit a healthcare worker) get the vaccine before me — a 45-year-old man with significant disabilities?

That’s not only a heartless decision, it’s bad policy. In dealing with the pandemic, Newsom often says he’s just “following the science.” He’s not doing that here. Studies show that people with disabilities who contract the virus are far more likely to die from it than the general population. In one study, researchers found that people with Down syndrome are nearly five times more likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19 than the general population and face 10 times the risk of death linked to the virus.

As Andrew Imparato of Disability Rights California told the state’s vaccine advisory committee last week, “From our perspective, if we wait until May to get [vaccines] to other populations, a lot of people under 65 are going to die unnecessarily.”

It’s not that states are powerless to help. A fair number of other states, perhaps recognizing the grim stakes, have stepped up to make people with disabilities a priority in their vaccine distribution plans.

Ohio is already vaccinating people with developmental or intellectual disabilities and certain medical conditions. Vermont plans to give priority to those with Down syndrome. Tennessee and Indiana put people with developmental and intellectual disabilities high on their lists. And Oregon even designated a drive-through vaccination center at Portland International Airport specifically for people with disabilities and their caregivers.

Where’s California’s plan? It’s desperately needed. Many people with disabilities are dealing with comorbidities of health that make us more vulnerable if we get the virus, while routine contact with multiple caregivers and other people who support us increases our risk of being exposed to COVID-19.

In addition, many people with disabilities are nonspeaking and may not be able to communicate that they don’t feel well. Others have sensory challenges that make it difficult or impossible for them to wear protective face masks.

Yet California has offered vaccines for the caregivers who support people like me — but has not accounted for the disabled people they care for who need it more. The state may view this as a way to “protect the vulnerable,” but you know what would help more? Administering the vaccine to us.

Out of the gate, California offered the COVID vaccine for staff and residents of long-term care facilities. Many people with disabilities are surrounded by such staff, but we’ve been left out.

As a person with cerebral palsy who lives on my own with support, I am more at risk because I rely on my staff to help me. I am exposed to multiple support people who come and go each day. Several of them have been exposed to COVID and had to isolate, although none of them have come down with it so far.

Still, I’m so afraid of getting COVID that many days I don’t even go out my front door to get some fresh air. My family raised me to be as independent as possible. Since March, I’ve felt like I am living in an institution. I’m so isolated.

California’s vaccine policy must be altered to make us a priority. The science says people with disabilities are disproportionately dying of COVID. Why isn’t Gov. Newsom listening?

Tim Jin, of Fountain Valley, serves on the board of Disability Voices United.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.