Op-Ed: Lessons from the civil rights struggle that began before the Civil War

- Share via

As Americans continue to grapple with racial violence and the legacies of slavery, it is worth remembering the roots of the movement that created the nation’s first federal civil rights law, passed by Congress 155 years ago this week.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 affirmed for the first time that people of African descent who were born in the United States were American citizens, and that citizens “of every race or color” were entitled to the same basic rights as white citizens.

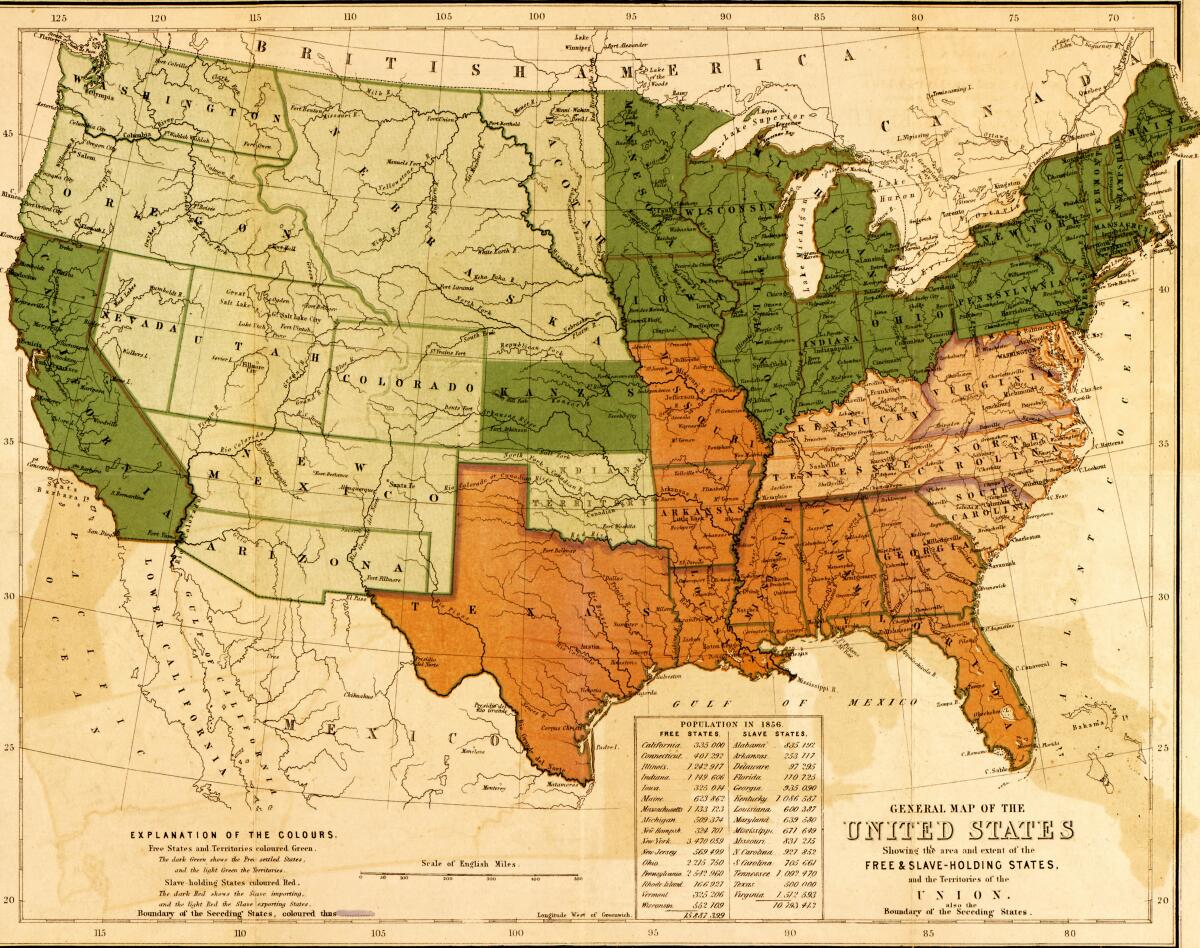

The Civil War was over and slavery had been abolished, but lawmakers who enacted the statute knew that additional measures were needed to secure true freedom. In fact, many had spent years in the movement to end racial discrimination in the free states of the North.

As today, politics varied from state to state. In the early decades of the 19th century, legislatures in Ohio, Indiana and Illinois adopted “black laws” designed to discourage African American migration. Those laws required free Black residents to register with county officials, forbade them from testifying in court cases involving whites, barred Black children from public schools, and reserved the vote for white men only.

Most Americans in that era believed the states were fully entitled to regulate and restrict the rights of their residents in almost any way they chose. Like those who advocate draconian restrictions on immigration today, legislators in the early 19th century insisted that free Black migrants were likely to become dependent on public alms, take jobs from white residents and commit crimes, so they pressed for laws designed to discourage migration.

Early civil rights activists deplored these ideas and demanded the repeal of state laws that explicitly discriminated based on race. The path they faced was almost inconceivably steep. African Americans, the people most hurt by such laws and most motivated to end them, were a tiny proportion of the population in the free states, and Black men and women were not allowed to vote.

African American writers, speakers and organizers spoke out against the black laws when they could. Despite the potential for violent backlash, in early 1837, a small group of Black men met in Cleveland and planned a campaign for repeal of the Ohio black laws and funding for Black schools. They chose Molliston Madison Clark, a teacher and theology student, to tour Ohio and galvanize people to action.

That summer, Black Ohioans launched a petition campaign from a statewide convention in Columbus. Their petitions insisted that racial distinctions in law were “not found in justice and equality,” and they pledged to keep fighting “till justice be done.”

White anti-slavery activists worked with Black activists against these state laws. Responding to petitions from these activists, Ohio state Sen. Leicester King delivered a report in spring 1838 that demanded that “in the administration of justice ... the same rules and principles of law should be extended to all persons, irrespective of color, rank or condition.”

Like so many other times in the centuries-long American struggle against racial oppression, King’s allies in the Ohio Legislature did not have the votes to get his proposals passed. But the report was widely reprinted, providing encouragement and hope for broader support.

The Ohio civil rights movement would see many more ups and downs in the next decade, as activists tried to persuade members of both major parties, the Whigs and the Democrats, to join them. They finally achieved significant success in 1849, when, by a hair’s breadth, the Ohio Legislature repealed most of the noxious laws that denied African Americans their basic civil rights.

Massachusetts and New York had no discriminatory residency laws, but in those states, Black sailors faced incarceration and sometimes sale into slavery when docked in Southern ports. Pressed by the anti-slavery movement, those two states in 1839 and 1840 empowered their governors to spend public funds to rescue Black residents who were trapped in Southern jails.

The cause was not without tensions and divergences. Most African American activists demanded full racial equality in political rights: the rights to vote, hold office and serve on juries. To their frustration, many white allies met them only halfway, fighting for civil rights — the rights to travel, to testify in court, and to sue and be sued — but hesitant to advocate for Black men’s right to vote.

Yet the movement gradually maneuvered from the margins of mainstream politics into the center — to the Republican Party, which ran its first candidate for president in 1856. The rights of free African Americans at first took a back seat to questions of slavery’s extension. Still, when Republicans swept into Congress and the presidency in 1860, their power enhanced by the secession of 11 Southern states, they pursued the civil rights agenda forged during earlier decades of struggle.

Those principles of racial equality were embodied in both the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the 14th Amendment, adopted in 1868, which declares unequivocally that all persons born or naturalized in the United States are U.S. citizens and forbids states from denying to any person, citizen or not, due process and equal protection of the law.

The history of the first civil rights movement offers several lessons for the present. Among them: Significant progressive change takes time. It is important to make strategic alliances with people you don’t completely agree with. A narrow win is still a win. Doors may open for reasons beyond your control. Use power when you have it, because moments of real opportunity are hard to come by.

Kate Masur teaches history at Northwestern University and is the author of “Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, from the Revolution to Reconstruction.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.