Editorial: The jury is out for Chauvin, but we all should be ready to rule on American policing

- Share via

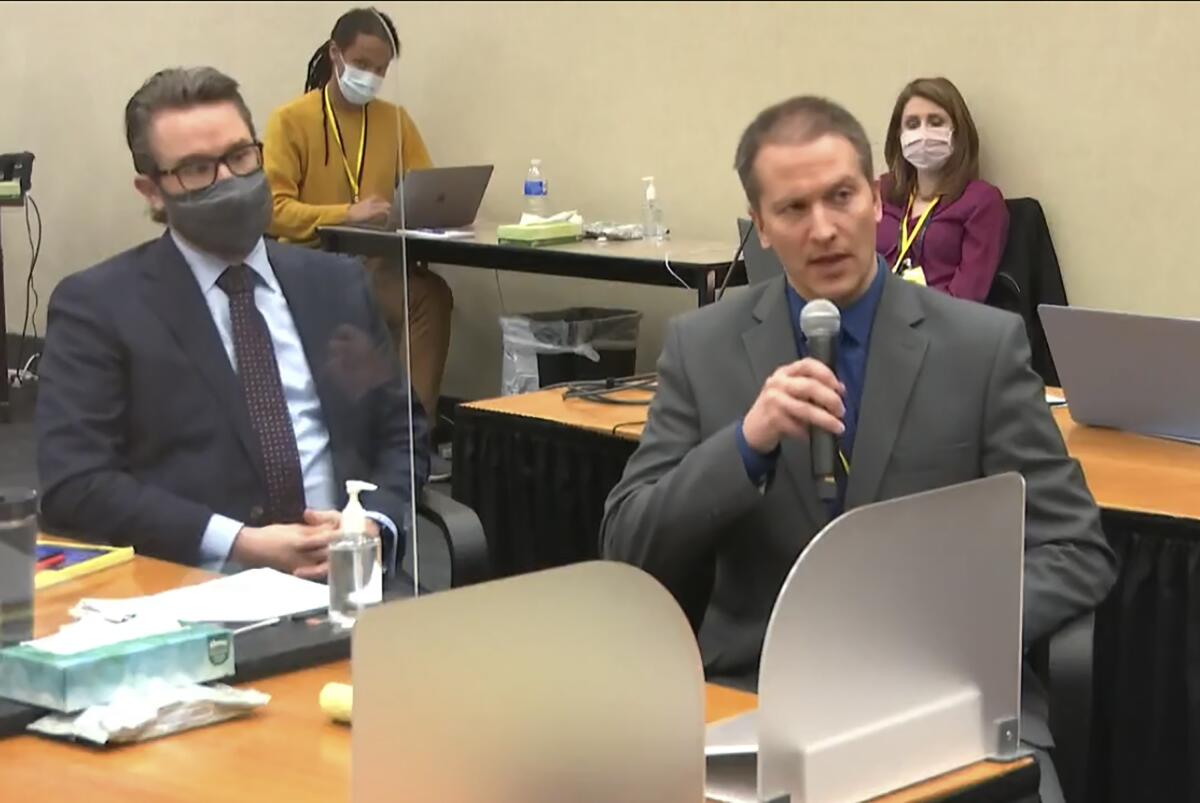

As the murder trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin in the death of George Floyd went to the jury Monday, a parallel case of sorts was resubmitted to an American public that already has been in contentious deliberations over the 30 years since Los Angeles police officers brutally beat Rodney King.

The question in Chauvin’s case is whether the officer’s actions on May 25, 2020, including his kneeling on Floyd’s neck for nine minutes and 29 seconds, were within the scope of what a “reasonable” police officer would do in the same situation, given what was learned at the time he was dispatched to the scene, what he found when he got there, what his training taught him and how his department’s policy guided him.

As excessive-force prosecutions of police officers go, this one was unusually strong, in part because of the testimony of Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo that Chauvin violated department policy in his use of force against Floyd — and in part because of the ready availability of damning video evidence. Even the defense’s repeated replaying of body-camera video as part of its closing argument served to underscore the brutality of Floyd’s arrest after he allegedly passed a counterfeit $20 bill.

Among the arguments offered by Chauvin’s team is that Floyd’s statement while under restraint — “I can’t breathe,” which chillingly replicated the final words of Eric Garner during his fatal 2014 arrest in Staten Island — is itself proof that Floyd could indeed breathe.

In the other case — the one being tried in the court of public opinion against American policing and its toll of (on average) 1,000 civilian deaths a year, with an astonishingly disproportionate number of Black deaths — two key bits of evidence were submitted while Chauvin was on trial in Minneapolis.

One was the apparently mistaken fatal shooting, a few miles away, of Daunte Wright during a traffic stop by a police officer who reportedly thought she was firing a Taser instead of a gun. Why do we want armed officers pulling people over for infractions like having expired tags or air fresheners hanging from their rearview mirrors?

The other exhibit was video released in the police killing of 13-year-old Adam Toledo in Chicago last month. Toledo may have tossed a gun behind a fence, but images show that his hands were empty when police shot him.

Conviction of Chauvin would suggest that he was atypical of police, acting outside the bounds of reasonable officer conduct — a rogue policeman, or a “bad apple,” to use the words often applied in the rare cases in which officers are actually found guilty of misconduct. Acquittal, conversely and perhaps ironically, would be another bit of evidence in the broader case against American policing. Policing as it is currently practiced in the United States is inherently unreasonable if it means a “reasonable” officer can cut off the oxygen to an unarmed person’s brain and keep doing so after that person stops moving — and stops breathing.

All Americans are the jury in the case against policing, and we have been debating a verdict for decades, asking to review material and reconsider arguments from each side. Video evidence has been mounting since a bystander tested his new camcorder at the scene of King’s arrest in 1991. Much of the weary American jury took a recess the following year after the acquittal of four LAPD officers triggered an outpouring of violence, but the jury reconvened in 2014 after the deaths of Garner and Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. We ramped up deliberations last year after Floyd’s death.

It’s time to render a verdict. Whether or not Chauvin is found guilty of murder, we are guilty of allowing American policing to go far too long without imposing significant changes on what kind of service to expect and how it is to be delivered.

In Chauvin’s case, after the jury retired, the defense raised the irresponsible statement by Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles) calling on protesters to get “more confrontational.” The judge denied mistrial but had appropriate words for Waters, calling failure to respect the role of a co-equal branch of government “abhorrent.”

But Waters is hardly alone. At least one group of organizers has called for a rally, after the Chauvin verdict is delivered, at Florence and Normandie, the place where the 1992 protests after the Rodney King officers’ verdict turned into a vicious attack on a truck driver and, from there, a deadly weeklong riot.

Americans will be holding their collective breath until the Chauvin jury returns a verdict. But even if the response on the street is calm — and we are all overdue for some calm — our daunting task remains in front of us, and we can hardly afford to wait another 30 years to complete it.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.