Op-Ed: So you want to write a COVID novel? Here’s an idea — don’t

On the morning of Sept. 12, 2001, I woke up and turned on the news. After a quick nervous breakdown, I opened my laptop to put the finishing touches on my appraisal of a quietly powerful literary novel I’d been asked to review around the time Mohammed Atta was traveling to Las Vegas on one of his many “surveillance” flights. How strange it felt to look again into a work of fiction that had no idea the world just changed — and how oddly difficult it was not to hold that against it. When I turned in my review later that day, instead of responding, “ARE YOU INSANE?” my editor, who lived within sight of the twin towers, said something about being glad to remember that life, somehow, had to go on.

If you’re a writer, disaster can feel perversely energizing. Early in this COVID-19 pandemic, a few optimists wondered how many wonderful novels, poems, plays and screenplays would result from national lockdown. I certainly hoped to crank out a few pages while pretending to spend time with my family. Turns out it’s pretty hard to write when a quick run to the grocery store feels like a John Carpenter movie and every time your kid coughs you lunge for a thermometer. I predict that a great outpouring of distinctive fiction, poetry or drama about this pandemic is unlikely.

To paraphrase Tolstoy, all global crises suck; but each sucks in its own distinct way. A lot of fiction writers, including myself, responded to 9/11 in their work, but much of that work was only glancingly about the day itself. What largely shaped storytellers’ reactions to 9/11 was our national mood, which ponged between feral sentimentality (angry, weeping talk show hosts) and dystopian absurdity (soldiers standing pointless sentry at deserted regional airports). We were in new and distressing territory as Americans, and the literature and film that grew out of the disaster reflected that.

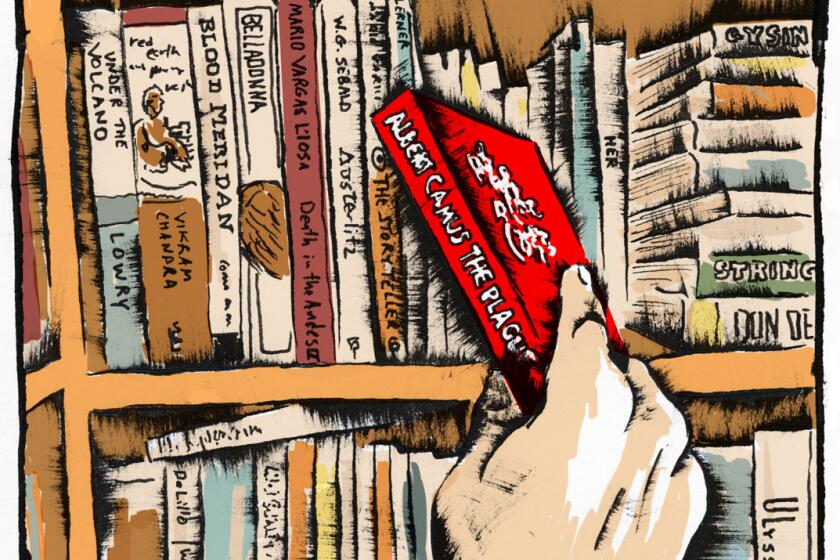

Albert Camus’ novel has an uncanny resonance with America’s health and political crises in 2020.

COVID-19, too, is very much a mood, but comparatively it’s an impoverishing and isolating mood. After 9/11, we left our homes and, however briefly, went into one another’s arms. On the evening of Sept. 11, 2001, roughly 150 Republican and Democratic lawmakers gathered on the East Front steps of the Capitol Building to belt out “God Bless America.” COVID weaponized gestures of human connection like these, while also making some of us wonder just what about America is worthy of blessing anyway.

One reason I’m confident there won’t be a lot of COVID literature is we’ve been here before, during the pandemic of 1918-19. When half a billion people got sick — and at least 50 million of them died — most writers shut their mouths. There’s Katherine Anne Porter’s novella “Pale Horse, Pale Rider,” and Yeats’ poem “The Second Coming,” written as his wife recovered from influenza. But as Virginia Woolf wrote in her pandemic-spawned essay “On Being Ill”: “Let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry.”

In many of the great plague stories, from “The Decameron” to Camus, illness is often a metaphor. COVID has been a straightforward reminder that illness is illness. I have a strong feeling that, when this pandemic is finally over, almost no one’s going to want to look back at what’s become, effectively, the dumbest morality play in human history. Gather round, children, and listen to the affecting tale of a well-meaning but ineffective majority wasting years begging a venal, oafish minority not to be sociopathic idiots.

Bissell, whose new collection “Creative Types” pokes fun at his own past, on the career turns that led, among other things, to “The Disaster Artist.”

A more formidable obstacle to a torrent of COVID fiction and drama has to do with their literary gatekeepers. As one editor put it to me, “Publishing a novel about COVID would, at this point, emotionally feel like giving yourself COVID. Which is callous to say, except that I’ve had COVID.”

But this sensation of wanting to escape the pandemic’s awfulness goes beyond gatekeepers. A great many of the creative types I know feel trapped and hopeless because of this disease. The general vibe from them all is: “Enough. Give me something, anything, that isn’t this.”

Does this mean we’re doomed to months or even years of positive stories, to a million Ted Lassos loosed upon this Earth? If so, by God, let them gambol across the fields of culture. It may be that remembering what’s actually good about human beings will be central to getting through this dismal epoch.

I can hear writers deep into their pandemic novels and screenplays suddenly exclaim, How, as writers, are we to maintain our relevance, if not by reckoning with an ordeal of this significance? And didn’t Gary Shteyngart just publish his COVID novel?

Second question first. Yes, he sure did. And people will buy and read it because it’s by a bestselling author, not because it’s about COVID.

Over lunch and cocktails, the satirical and melancholy novelist unpacks his raucous new Hudson Valley pandemic-era novel, “Our Country Friends.”

As for the first question: Chasing relevance by reckoning with reality has always had a dubious relationship to artistic achievement. One of America’s greatest writers, Herman Melville, once sat down to reckon with reality, hoping to write a novel so of the moment that he’d put himself back in the game, commercially speaking. The result was “White Jacket.” On naval flogging. You haven’t read it for a very good reason.

Creatively speaking, COVID’s spread and reach is a big part of the problem. The greatest fictions about human disaster are able to put you where you haven’t been: on the battlefield, in the concentration camp, among the refugees. But COVID is a battle we’ve all fought, in one way or another, and its camps look startlingly similar to our living rooms.

Exploring shared trauma through the matrix of storytelling ranks among the noblest imperatives of narrative art. So perhaps the novelist or filmmaker will eventually emerge that’s capable of convincing me that the story of our shared misery could be something other than miserable.

However, I suspect that the artist in question will need considerable distance from these early, ugly days. In other words, by the time this person comes along, I’ll be long dead, and so will you, and Upsilon variant 7.31 will be tearing through the Arctic fishing village of New Detroit.

Tom Bissell is an author and screenwriter. His new book, “Creative Types and Other Stories,” was published this month.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.