Op-Ed: California’s blocked vaccine mandate for prison guards is public health idiocy

- Share via

California’s correctional facilities in January saw an alarming third wave of infection that brings an urgent threat.

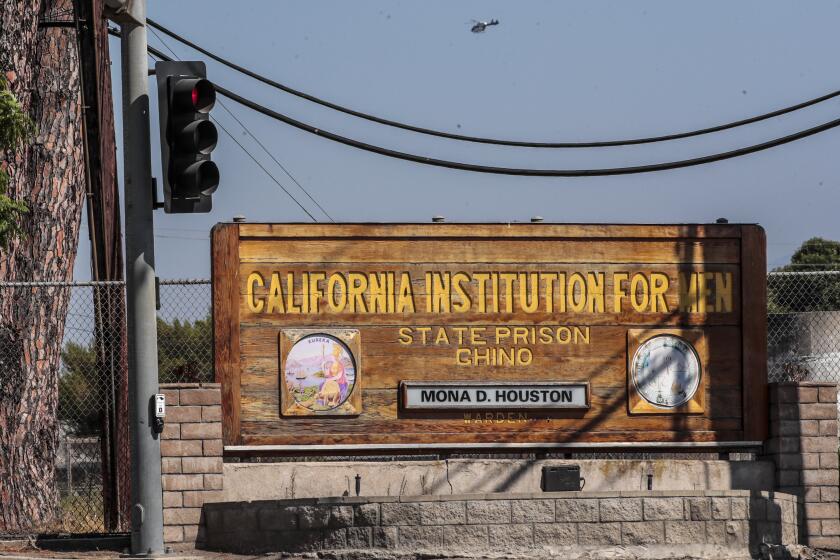

The first wave, during the spring and summer of 2020, saw disastrous infections starting at the California Institution for Men and leading to cases in most residents at Avenal and San Quentin. The second wave, during the winter of 2020, saw outbreaks across all prisons with thousands of active cases. More than 66,000 infections have occurred to date, and at least 246 incarcerated people have died of the virus.

Squeezing two people into each cell has had a predictable outcome, with 335 new infections in a two-week period.

But this third wave features another cause for alarm: As of Jan. 28 there were 4,337 active cases among prison staff, with this surge seeing faster spread for that group than at any other point in the pandemic.

With staff moving freely in and out of these facilities, they have been agents of contagion in prisons and their surrounding communities. Data that I collected with independent researcher Chad Goerzen, as well as a report published by the Prison Policy Initiative in December 2020, show considerable correlations between prison COVID spikes and outbreaks in nearby counties and indicate that staff are primary drivers of this trend. And despite all these risks, they still are not required to get vaccinated.

After the federal receiver in charge of California’s correctional healthcare system pleaded for a vaccine requirement, U.S. District Judge John Tigar finally ordered one in September — only for Gov. Gavin Newsom, otherwise a staunch vaccine supporter, to side with the corrections department and the guards’ union in opposing the mandate. Their appeal is still pending with the 9th Circuit, and at this point there is no general requirement that prison staff become vaccinated.

The main concern of opponents of the mandate is that it might lead to mass resignations of guards, which in turn would result in understaffed, unsafe prisons. Yet in other sectors with mandates, such as schools and government offices, vocal protestations and resignation threats gave way to vaccination compliance. Indeed, the opponents’ rejection of a vaccine mandate is creating the reality they warned of: As of last week, 21 prisons each had more than 100 infected staff members, who then could not safely show up for work.

California’s prisons reported 3,845 active coronavirus infections among state employees Monday, a 212% increase so far this month.

The irony of the situation might be lost on prison authorities, but it has an even darker side. Even if the threat of correctional officers’ resignations over a mandate were real, and graver than the very real staffing problems generated by the spike in staff cases, why do government officials so stubbornly support overcrowded prisons? Exposing incarcerated people to a serious virus with no means to protect themselves from unvaccinated staff members — amid other health order violations in prisons, per multiple reports — violates their 8th Amendment rights.

For the sake of public health, the state should withdraw its appeal of the court ruling on the mandate for prison guards, and Newsom should stop supporting the guards’ resistance, in accordance with his position on vaccination at other congregate spaces.

Ultimately, to protect California’s prison populations and everyone in surrounding counties, not only from this pandemic but from others in the future, we need to confront the larger truth: If it is impossible to retain enough correctional staff to provide proper care for our incarcerated population, then we cannot incarcerate as many people as we do.

We cannot, lawfully and constitutionally, house, clothe and feed more than 100,000 people, many of them aging and sick, if the staff cannot be bothered to take minimal precautions to protect those people from disease.

California needs a lasting policy of releasing inmates — shown to be an effective intervention to reduce COVID cases — taking into account criminologically and medically relevant factors such as their age and health conditions. (When only 7,600 people were released from California’s prisons in summer 2020 as a COVID mitigation measure, fewer than 1% were in a medically high-risk category; most were younger people about to be released anyway.)

One cliché of the pandemic has been that “we are all in the same storm, but not in the same boat.” This is true both behind bars and on the outside. Requiring prison staff to be vaccinated, while reducing prison populations through targeted release, protects everyone’s interests in the years to come.

Hadar Aviram is a professor at UC Hastings College of the Law and participated in the San Quentin COVID-19 litigation as counsel on behalf of ACLU of Northern California and criminal justice scholars. She is the co-author of the forthcoming book “Fester: Carceral Permeability and the California COVID-19 Correctional Disaster.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.