Op-Ed: How superhero comics became my springboard to questioning the way things are

- Share via

As a young Black boy in the 1970s, one who was queer but didn’t exactly know it, I was taught next to nothing in school about slavery (other than Lincoln’s heroics in ending it) and absolutely nothing about the cornucopia of possibilities for one’s gender or sexuality. Yet even in my elementary school years I knew that anti-Black racism was powerful. I resisted and challenged white supremacist ideas when I could identify them, and I had a strong aversion to injustice.

Reading superhero comics was a powerful and unexpected source for my willingness to question the status quo. Those frequently dismissed, unrealistic, action-adventure stories about mostly white male heroes that were written and drawn almost entirely by white male creators fostered and honed my powers of imagination.

My experience suggests that even if some of the recent harmful curricula and book bans succeed in restricting kids’ education, there’s hope that they will fail in their ultimate aim. At least some of today’s youth will find what they need to learn and thrive elsewhere, despite the unnecessary damage these attacks on academic freedom inflict on them.

The complicated connections and lore found in my comics collection was just the kind of system that helped me bond with my science-loving son.

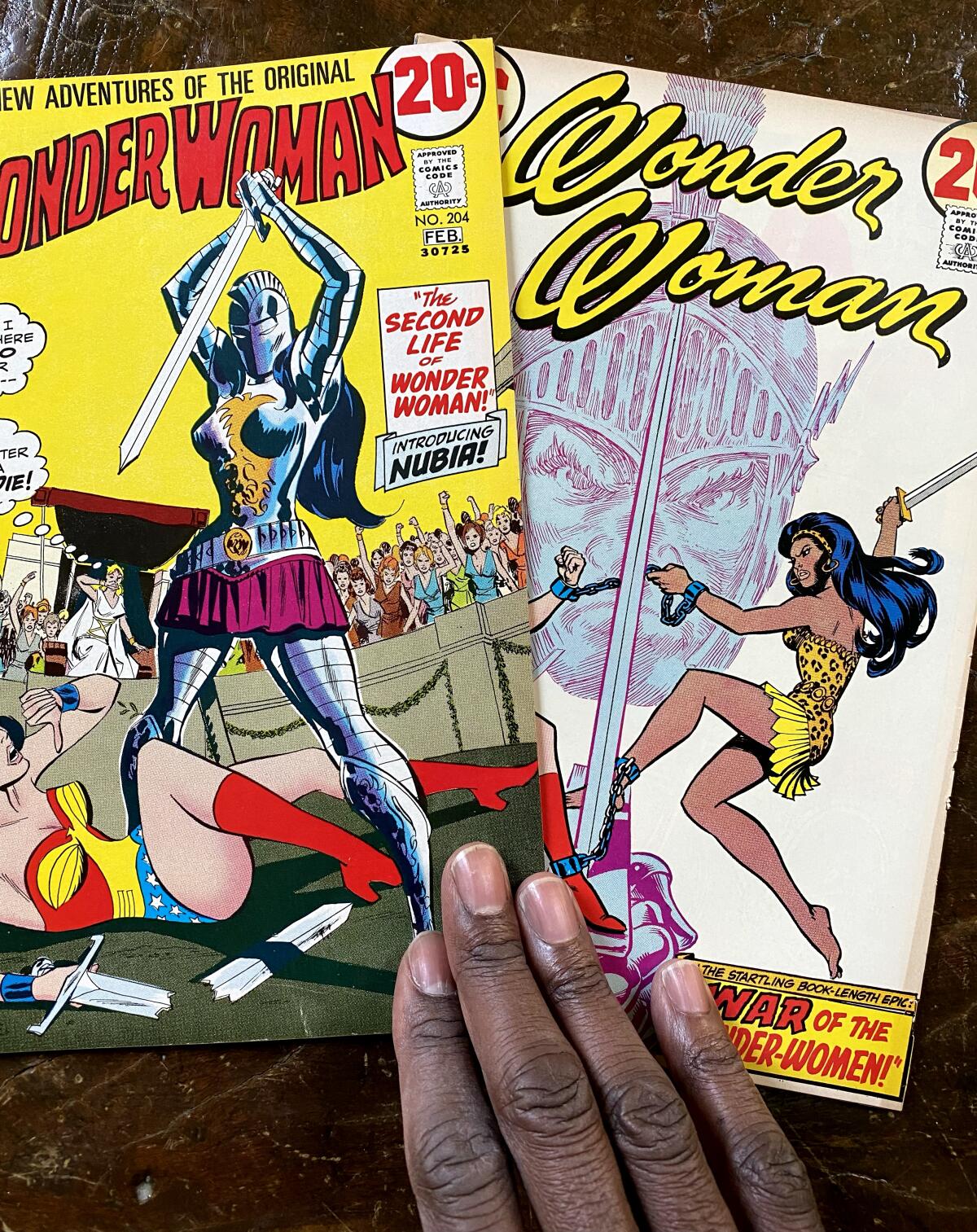

None of my favorite superheroes, such as Thor and Dr. Strange, had as powerful an impact on my childhood imagination as the little-known Nubia, Wonder Woman’s Black twin sister. Endowed with all the gods-given superhuman gifts and martial prowess of her iconic sister, Diana, Nubia’s story was revealed over the course of three issues of Wonder Woman comics in 1973. She became a footnote known mostly to superhero comics cognoscenti, however. Nubia and her shared parentage with Wonder Woman were blotted from two-dimensional existence by DC Comics’ successive rounds of reboots starting in the 1980s.

But I happened to see one of those first issues when I was in third grade in 1973, living on an Army base in West Germany where my father was stationed. And because I saw it, I started reading superhero comics.

Nubia was created as part of DC Comics’ attempt during the 1970s to integrate its all-white roster of superheroes and broaden its consumer audience, following the splash made by rival Marvel Comics, which had introduced the Black Panther in 1966. But unlike other contemporaneous DC Comics assays in racial diversity, such as now-mainstay character John Stewart (the Black Green Lantern), Nubia didn’t become a consistently recurring character in DC’s fantasy world.

Her commercial failure didn’t stop me from taking Nubia to heart and making her a star in my own imagination. Nor did it, evidently, for many others. After nearly 50 years of rare appearances in comics, Nubia — or new versions of the original (she’s no longer Wonder Woman’s twin) — has been revived. 2021 brought us the miniseries “Nubia and the Amazons,” as well as a young adult graphic novel, “Nubia: Real One,” starring a teenage Nubia.

While fantasy is often thought of as an escape from reality, primarily of value if it offers a blueprint for some utopian future, Nubia taught me that fantasy can be an active engagement with reality and a basis for questioning the present. A significant part of her appeal is, of course, her depiction as a super-powered Black woman, very few of whom are a part of the superhero comics mythos. But for me, the greater part of Nubia’s intrigue was the way she lent herself to my imagination, how she was a springboard into my fantasies of beautiful Black powerfulness — despite, or perhaps even because, she was so underutilized in the comics.

Black superheroes are popular onscreen thanks to the work of Black creators of comic book characters and stories that anticipated this racial reckoning moment.

Nubia’s anomalous but sporadic presence as a Black woman super-warrior made her an especially fruitful catalyst for fantasy. This is because comics require imagination to engage with them; they require imagination just to animate and connect the static pictures of each panel on a page. Learning this fundamental requirement for reading comics — active imagination — allowed me to envision connections between the panels that showcased Nubia that fit my own fantasies, where I created adventures for her that never saw the page. This practice was key to the development of the imagination I needed to navigate a world that constantly reminded me of my differences as Black, and as gay.

My ability to envision fairness that doesn’t exist was honed by reading superhero comics because every superhero is engaged in a battle for justice. Watching Wonder Woman identify the wrong in sexist men’s perception that she wasn’t strong helped me to identify the wrong in the racism of the world I lived in.

Reading superhero comics can satisfy the common desire to be a different person than you think you are — more athletic, prettier, smarter, funnier, more popular. It can also provide a vector for wishing that the world you live in was different.

Right now, many people are trying to prevent kids from reading books that talk about “otherness” — especially as it relates to race, queerness and gender identity — by banning titles from school curricula and libraries in record numbers. With her recent revival, some of the kids who are being “protected” through book bans will find Nubia, or they’ll find their own version of her. Being actively and imaginatively in superhero comics can allow you to see yourself, and the world, differently. Reading those comics will help prepare kids to resist the real-world afflictions they are already encountering, just as Nubia did for me.

Darieck Scott is an author and a professor of African American Studies at UC Berkeley. His most recent book is “Keeping it Unreal: Black Queer Fantasy and Superhero Comics.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.