Castellanos Elementary sits just two blocks from the vehicle-clogged 10 Freeway in a part of the Pico-Union neighborhood with few parks and a lot of auto repair shops.

It’s one of L.A. Unified School District’s newer campuses, built 12 years ago. But the dual-language charter school’s more than 450 students, almost all Latino, have hardly any green space — just a 100-foot-wide play area of scraggly grass and dirt without a working sprinkler system. The gated, fenced and walled-off campus is mostly paved over with asphalt that absorbs the sun’s rays and radiates heat throughout the day.

There are few trees to shade the blacktop, so students often gather in the shadows of the school’s two-story buildings to stay cool. Children are constantly getting scrapes from the asphalt, said school operations manager Carla Rivera, and on hotter days they sometimes have to be kept inside.

The experience is sadly typical of schools across Los Angeles, where too many children are forced to learn and play in paved-over, fenced-in and often treeless campuses that draw apt comparisons to prison yards or parking lots. These conditions are detrimental to learning, health and well-being, and especially harmful because they are so common in the same low-income communities of color that already suffer from a lack of tree canopy, park space and higher exposure to heat and pollution.

Lawmakers should get behind legislation to make California the first state in the nation to rank heat waves, a step that could save countless lives.

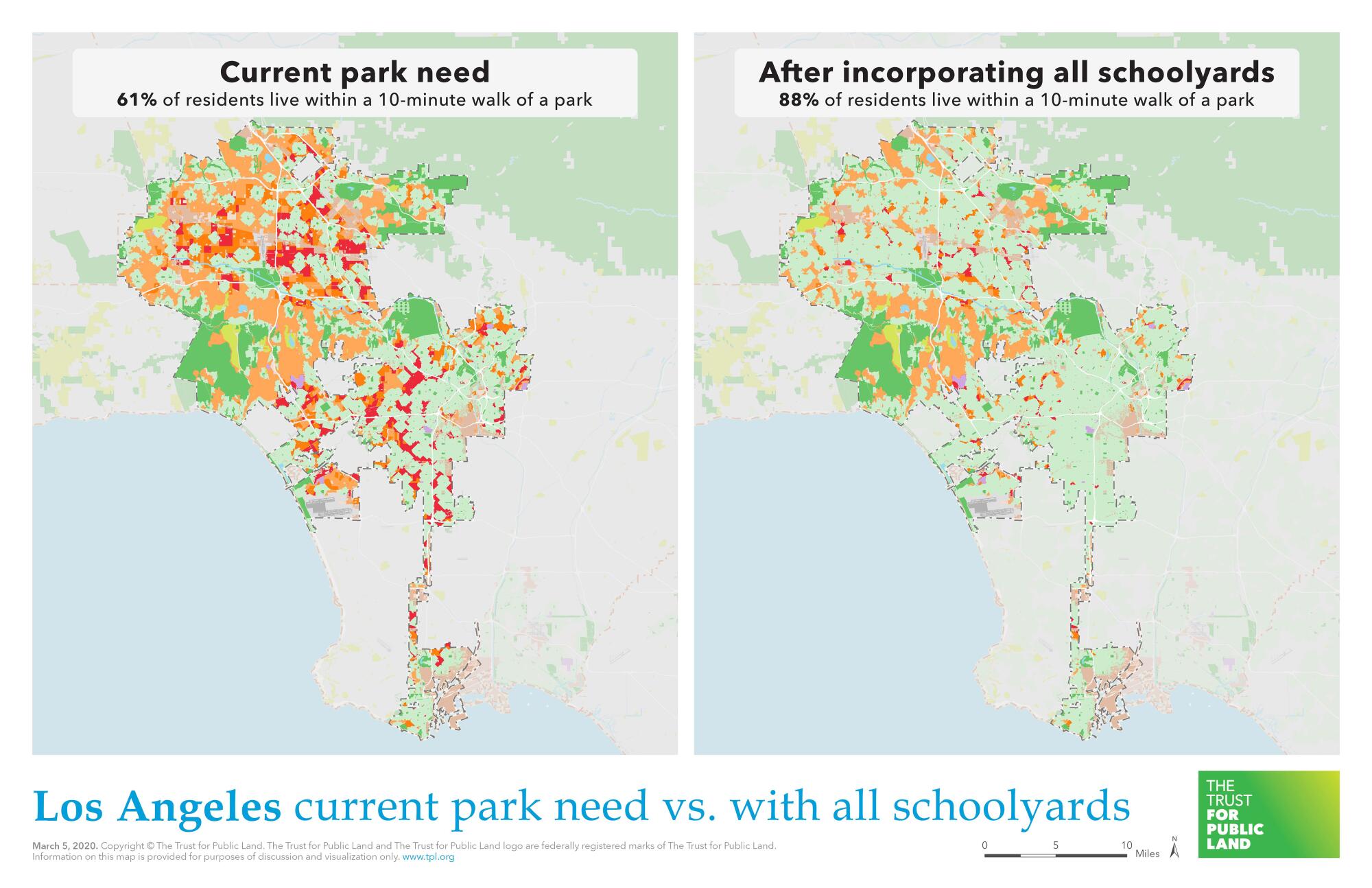

L.A. Unified’s new superintendent, Alberto Carvalho, quickly identified the lack of green space on district campuses as a problem, pointing it out repeatedly during school visits in his first few weeks on the job. He told The Times editorial board last month that “where we put kids to play ball, to exercise, to do jumping jacks, to play hopscotch, it does not make sense.” He also noted that many of the schools that lack green space are in the same neighborhoods that suffer from park scarcity.

“So when do the kids ever get to see something other than the concrete jungle that surrounds them?” Carvalho said. “I think it is our moral responsibility to provide that.”

He has promised to release a plan within his first 100 days to green schoolyards, starting with asphalt-dominated campuses in neighborhoods with the greatest need for open space. He said it would be “systemic district-wide plan” rather than “a symbolic, one-off approach.”

‘So when do the kids ever get to see something other than the concrete jungle that surrounds them? I think it is our moral responsibility to provide that.’

— Alberto Carvalho, L.A. Unified’s new superintendent

That commitment is welcome, but it shouldn’t have taken new leadership to pay attention to this obvious problem. Community groups and advocates last year launched a campaign urging the district to remove asphalt from its most paved-over schoolyards, replace it with park-like amenities such as trees, soil, mulch and plants, and provide public access to their outdoor spaces after school and on weekends. The Los Angeles Living Schoolyards Coalition, made up of community groups, nonprofits and researchers, wants LAUSD to green up 28 school sites in time for the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics.

It’s not just a matter of aesthetics, but educational opportunity and environmental justice. Research shows exposure to the outdoors and access to park space are good for children’s mental and physical health and development: They reduce stress, increase the ability to concentrate and boost academic achievement. Replacing asphalt is also necessary to protect communities from extreme heat that is getting worse with climate change.

Paved surfaces, tree cover, and home construction quality can make the difference between heat waves being an inconvenience or a threat to your life.

L.A.’s schoolyards are contributing to the heat island effect, in which neighborhoods with few trees and a lot of paved, heat-absorbing surfaces — where Asian, Black and Latino residents are more likely to live — can be 10 degrees higher than surrounding areas. Though global warming is amplifying those disparities, they are the product of decades of discriminatory policies, including environmental racism and historical redlining, that excluded communities of color from real estate investment, parks and open space while saddling them with polluting industries.

Fortunately, Castellanos Elementary will soon transform a portion of its hot hardscape into a living schoolyard in a project expected to break ground this year. When it’s completed, there will be a multi-use turf field, more than two dozen new trees, play structures, shaded outdoor classroom areas with log and boulder benches, a stormwater-capturing arroyo and sunlight-reflecting paint to cool the asphalt that remains, among other improvements. The $1.5-million urban greening project by the Trust for Public Land, modeled on similar projects in Oakland, New York City and other communities, is being paid for with state climate funds from California’s cap-and-trade program and contributions from philanthropic groups.

As part of the years-long process to plan the school’s greening, Castellanos students were asked what they wanted, and many of their requests have been incorporated into the design. Their wish list is heart-wrenching because it shows kids’ intuitive understanding of what they deserve, and what they have been denied: a rainbow-colored running track, a shade gazebo, a garden, a nature play area, a new irrigation system and a “playground for big kids.”

It’s crazy that Angelenos would have to go to the ballot to force the city to implement its own plan to build bike and bus lanes and safer streets.

But the removal of more than 1,500 square feet of asphalt at Castellanos Elementary is ultimately just one project in a district with more than 1,000 schools. Advocacy groups say that despite some success at individual school sites, district and state bureaucracy is a barrier to removing asphalt from school campuses across the city, sometimes because of concerns about increased maintenance costs or due to space requirements for activities like basketball, tetherball and four square that restrict the number of trees and amount landscaping that can be planted.

“Greening school campuses is more than adding a vegetable garden or a few shade trees on a campus; it is about addressing systemic injustices that riddle the public education system and must be tackled in a comprehensive and coordinated manner,” said Robin Mark, Los Angeles program director for the Trust for Public Land, a nonprofit that works to close the equity gap in access to parks and the outdoors.

Converting schoolyards will cost money, though less than $2 million per school, which is far less than it would cost to build a park or expand an existing one. Leaders should make these projects a top priority to secure both public and private funding. Advocacy groups say there’s potential funding available from a parcel tax L.A. County voters approved to pay for parks and open space, as well as money set aside to treat and capture stormwater and urban greening funds in Gov. Gavin Newsom’s $37-billion proposal to fight climate change.

Let this be the year we harness our collective anger and demand politicians finally do what is necessary to prevent catastrophic climate change.

L.A. Unified officials should also work closely with the Newsom administration, which in an extreme heat plan earlier this year recommended partnering with school districts and community groups to accelerate school greening projects in climate-vulnerable communities. Joint-use agreements should also be pursued to provide reasonable public access to the green schoolyards wherever possible.

The problem is not a lack of space — LAUSD is the L.A. area’s largest landowner — but how it is used. Covering so much land with pavement has been a district strategy to save money on maintenance (asphalt is easier to take care of, day to day, than grass, trees and plants) and to provide flexibility for other uses like portable classrooms. But the benefits of a healthy outdoor environment for children to play and learn are more valuable than that. School district leaders should know better, and need to work with urgency to start greening schoolyards now.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.