Op-Ed: By backing Putin’s long reign, ordinary Russians share responsibility for the war

Is it appropriate for the United States and other countries to impose hardships on Russian citizens because of war crimes committed by their country’s forces in Ukraine?

Most Russians do not bear criminal guilt for what has occurred in Ukraine since Feb. 24. Only those who command or directly participate in attacks on Ukrainian civilians and civilian property and infrastructure deserve to face criminal punishment. But the great majority of Russians have made this war possible by allowing President Vladimir Putin to consolidate absolute power over the last 22 years. For that reason, they share political responsibility for the horrors now taking place in Ukraine.

To the extent that Russians know what is happening in Ukraine, many may deplore their country’s actions in Ukraine. They may not wish to force millions of Ukrainians to flee their homes, communities and country. They may not wish to contribute to the maiming and killing of those who have remained behind. They may regret the destruction of Ukrainian villages, towns and cities. Yet they made these crimes possible.

Biden’s ad-lib in Warsaw about Putin was just his latest in a string of gaffes. But it’s worrisome if those gaffes are informing American policy.

Of course, Putin is doing everything he can to prevent Russians from knowing what is being done in their name, even barring the media from calling the war a war. Those who call it a war, rather than “a special military operation,” may be prosecuted under a new law that punishes dissemination of information the government deems false with up to 15 years in prison. Russians cannot turn on their television sets and see ruined homes and apartment buildings in Ukraine, the dead bodies of Ukrainian families lying in the streets or the trains packed with Ukrainian mothers and children fleeing for their lives. Even so, most Russians know that the war is taking place, if only because international sanctions are causing them to suffer the economic consequences.

Ordinary Russians may feel helpless now to do anything about the crimes in Ukraine. But they had their chance during the two decades that Putin has consolidated absolute power. Some who tried to prevent Putin from doing so — such as human-rights researcher Natalia Estemirova, journalist Anna Politkovskaya and opposition leader Boris Nemtsov — were murdered. Putin’s main political opponent now, Alexei Navalny, barely survived an assassination attempt, only to be sentenced to nearly 12 years in prison.

But they are the exceptions that prove the rule. Putin has launched other military conflicts in his effort to extend Russian control over former Soviet territories, including the 2008 war in Georgia and the annexation of Crimea in 2014. An overwhelming majority of Russians cheered him on then, and his popularity soared once again in the runup to the invasion of Ukraine.

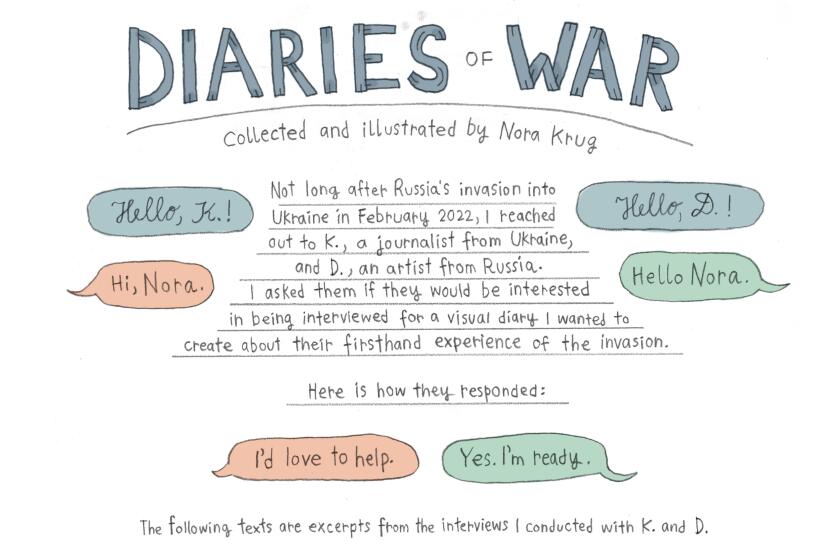

Follow K. and D. as they and their families confront the consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

So Russians knew what they were doing when they enabled Putin to remain in power for such a long time, and most demonstrated strong support for his rule. Russians collectively made it possible for Putin to carry out his political agenda by criminal means. Accordingly, Russians collectively share political responsibility for these crimes.

Thousands of Russian antiwar protesters have been arrested. They knew they risked being detained and losing their jobs, so their participation in demonstrations took courage. If there had been many more like them, the sanctions-induced hardships ordinary Russians now face would not be justifiable. But there were not many more of them. A larger outpouring of dissent might have shortened Putin’s reign or at least prevented him from becoming an absolute ruler, making it harder for him to launch a war unilaterally.

The West’s measures against Russia are unprecedented in size and scope, and it will be hard for Putin to discount them as he considers his options. But Putin and his inner circle are unlikely to suffer from any losses to their material well-being. The ordinary Russians who are suffering from the sanctions have only themselves to blame.

Aryeh Neier is president emeritus of the Open Society Foundations and a founder of Human Rights Watch.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.