Op-Ed: Fentanyl pill producers used to mimic other pharmaceuticals, now they don’t have to

In late August, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration warned that candy-colored pills containing fentanyl were showing up in seized drug loads coming out of Mexico. No longer were the fentanyl pills strictly blue, as had been the case.

The brightly colored pills, in shapes resembling legitimate pharmaceuticals, the agency reported, seemed an attempt to attract young people and children.

Activists scoffed, claiming the DEA was alarming the country with a narcotic scare tactic.

Indeed, I suspect it’s unlikely that Mexican drug traffickers intend their wares to target elementary school kids, though counterfeit pills containing fentanyl have found a market among naïve high school students, as the accidental overdose death of 15-year-old Melanie Ramos in Hollywood last month made clear.

Children are being poisoned by fentanyl, a deadly opioid. Here’s how a family therapist suggests telling kids about it.

But the cheery-colored pills are nevertheless ominous for what they indicate about the underground pill producers in Mexico, as well as the spread of fentanyl addiction across the U.S.

As this pill boom emerged back in 2017, Mexican traffickers, like counterfeiters everywhere, aimed to imitate the real thing: They made lookalike pills for blue 30-milligram oxycodone pills, the most popular, but also Percocet, Xanax and others. Those pills “were popular with the white-collar crowd who would typically shun ‘junkies,’ [and] would have been surprised to know that those pills were coming from [Mexico] just like all the cocaine and heroin,” one of the first couriers to transport pills into San Diego told me in an email.

A woman in recovery from fentanyl pill addiction told me that in 2018 she lived in Nogales, Mexico, taking the pills into southern Arizona. At first, she said, “we thought they were real.” They went for $20 apiece in Tucson then.

That easy money attracted a flood of new pill makers. The street retail price has dropped to between $2 and $5 per pill today in southern Arizona. The first large pill seizure out of Mexico is believed to have been in 2017: 12,000 pills in San Diego. Federal authorities seized almost 10 million pills in Arizona alone last year.

Amid this pill rush, she told me, producers “stopped caring how good [the pills] looked.”

This made business sense, since on the U.S. side addiction to fentanyl soared with these vast supplies. Pill pressers’ first target market was people addicted to expensive, now-scarcer legitimate prescription pain pills. Before long, though, the huge supply of fentanyl pills made access and addiction easy for people with little opioid experience. For these users, what the pills looked like didn’t matter, provided they contained fentanyl. Nothing else would put off fentanyl’s ferocious dope sickness.

“Now they’re in different colors — they’re clearly counterfeit,” a recovering fentanyl pill addict in southern Arizona told me recently. But “as long as it gets them high, nobody cares.”

Since its appearance on American streets, fentanyl’s spread has been due to its mighty addictiveness, and also to a sleight of hand. It was first mixed, often poorly, by street dealers into heroin, cocaine, meth and now occasionally marijuana — to boost both the drug and addict, but often also kill the consumer.

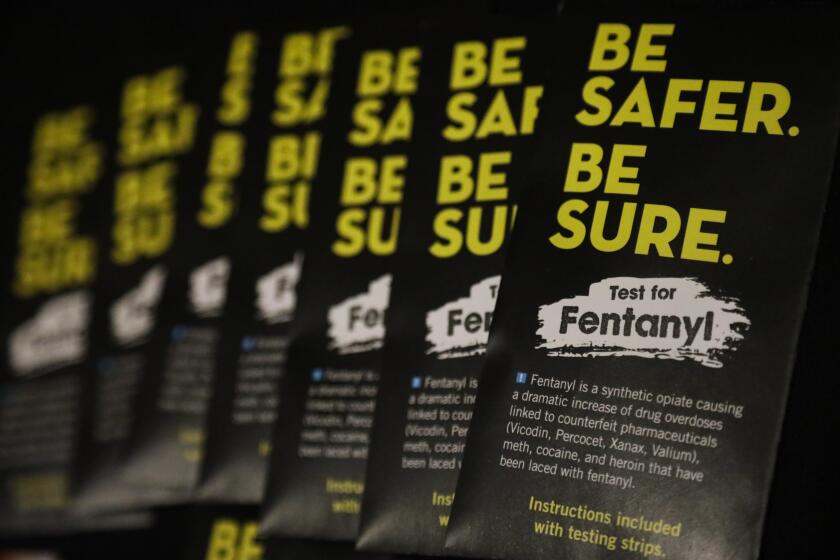

Fentanyl is often accidentally ingested, killing thousands of Americans a year. Home test kits and a readily available nasal spray could help save lives.

Fentanyl pills are just Mexican traffickers’ more sophisticated version of that ruse.

Mass supplies of these pills emerged not because there is some directive, some iron control from the top, but because there is not. It’s a broad free market of dozens, perhaps hundreds, of pill pressers in Mexico, imitating one another, fueled by largely unconstrained access to world chemical markets and little law enforcement scrutiny.

A drug-trafficking source from the Mexican state of Sinaloa told me some of the producers stopped trying to copy pharmaceutical pills last year when they began making pink pills. Those sold well, he said. Recently, packs of pills colored yellow, orange, red and purple also appeared, earning the name “skittles” on the street.

Drug counselors and addicts in southern Arizona reported that some users could smoke 50 to 100 pills a day, relentlessly using to keep withdrawal symptoms at bay. It’s unlikely that such a large group of people has ever achieved such mighty opioid tolerances. But even those who appear to have powerful tolerances eventually succumb. As one drug counselor in Arizona told me, “There are no long-term [illicit] fentanyl users.” They all die.

This is the result of the staggering numbers of these pills cascading into the U.S. The candy-colored pills are just the final sign that, unlike counterfeiters everywhere, Mexican pill makers have given up any pretense of imitating the real thing — because they can.

Sam Quinones, a journalist, is the author, most recently, of “The Least of Us: True Tales of America and Hope in the Time of Fentanyl and Meth,” which will be released in paperback in November.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.