Opinion: Why are we denying people with opioid addiction the most effective treatment?

- Share via

When you receive a scary diagnosis — for cancer, heart disease or other serious illness — one of your first calls is probably to a doctor who can offer the full range of evidence-based care. But if your diagnosis were for opioid addiction and you came to see me, an addiction specialist, federal regulations written half a century ago would bar me from prescribing the most effective treatment: methadone.

The U.S. lost more than 100,000 people to overdoses in 2021 in a crisis now dominated by fentanyl and other synthetic drugs. That’s more than twice the number of deaths at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in 1995. When officially tallied, overdose deaths in 2022 will also exceed 2020 levels.

Last month, the FDA made naloxone — the safe and effective drug that can reverse an overdose as it’s happening, of which Narcan is the best-known brand — available over the counter. If manufacturers set an affordable price, expanded access to naloxone could save countless lives. Expanded access to methadone would do the same.

The town of Española, N.M., has struggled with drug addiction for generations. But fentanyl has contributed to rising homelessness and overdose rates.

In contrast to the fatalism with which opioid addiction is usually portrayed, it is treatable. People recover. Long term, the best treatment involves the opioid medications methadone or buprenorphine in addition to offering counseling or therapy, all part of a harm reduction approach that meets patients where they are in their relationship to drugs. Decades of research have shown methadone to be the most effective medication for addiction ever developed. Buprenorphine, a different long-acting opioid, is similarly effective. Both reduce overdoses and can reduce drug use, crime and HIV transmission. They save lives at a comparable rate as giving aspirin for a heart attack. I’d go as far as calling them miracle drugs.

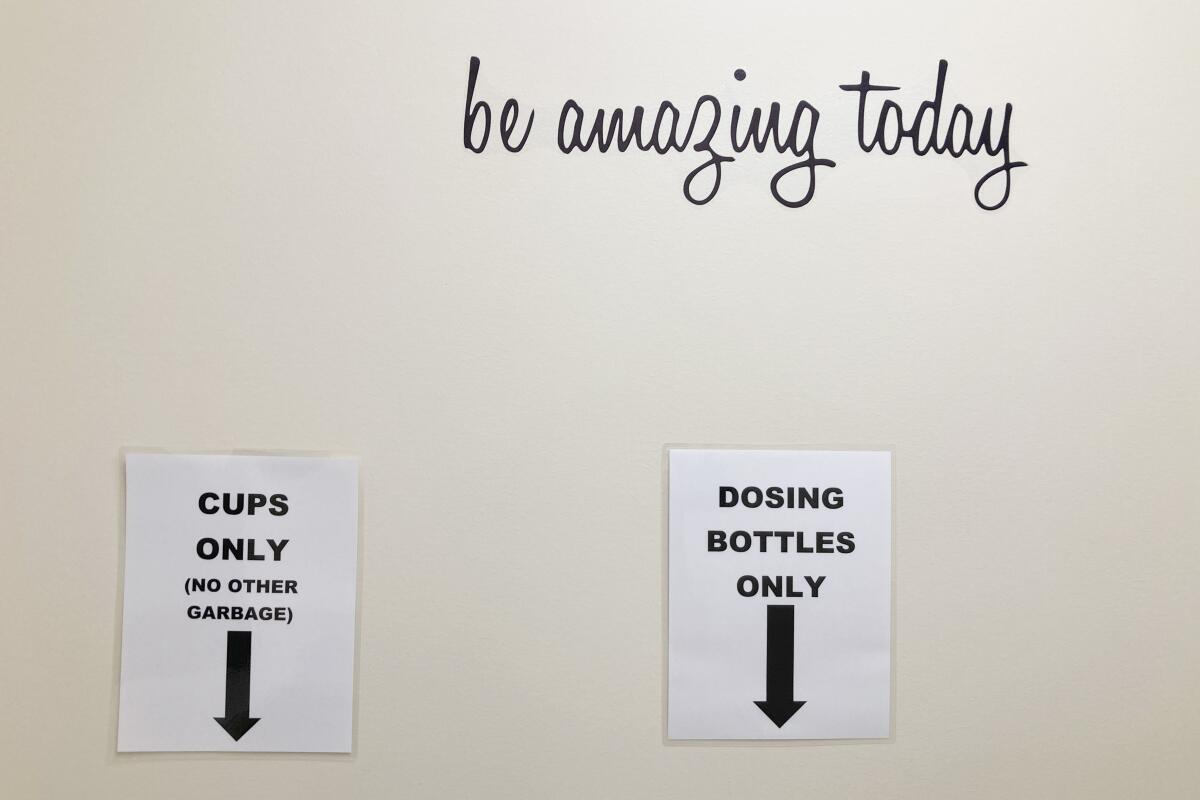

So why are doctors like me still barred from prescribing methadone? If I want my patients to access this medication, I can only refer them to “opioid treatment programs” that offer methadone in highly structured environments. These clinics can be deeply therapeutic for some patients — but they are shockingly hard to find. There are fewer than 2,000 opioid treatment programs across the entire country, and as of 2018, 80% of U.S. counties lacked a single clinic. Patients lucky enough to live near one are required, also by federal regulation, to show up typically six days a week to have staff hand them their daily methadone and watch them drink it. Patients who miss a dose because of a snowstorm, last-minute job interview or family emergency have no other way to access methadone and are forced to struggle through painful withdrawal symptoms.

If this whole system sounds onerous, it’s because it was designed to be. It was developed in the early 1970s by what is now the Drug Enforcement Administration, in the shadow of President Nixon’s war on drugs. Methadone can be dangerous if misused, and at the time it was novel to treat opioid addiction with an opioid medication. Thus the system’s architects focused on preventing patients — whom they stereotyped and assumed to be Black and Latino — from selling or giving away their methadone. Fifty years on, despite decades of evidence and experience, controlled programs remain the only way for people with opioid addiction to receive methadone.

This year brought progress for safely getting opioids to people with debilitating pain.

Fewer than 10% of people with opioid addiction are receiving treatment with medications in the midst of the worst overdose crisis in U.S. history. In December, Congress removed one barrier to treatment: Any clinician with a DEA license can now prescribe buprenorphine for opioid addiction. As powerful as this medication is, though, some patients do not respond to buprenorphine, or they prefer methadone. We urgently need to listen to the patients, clinicians and public health experts calling to make methadone more available.

The first and most essential change would be to allow board-certified addiction specialists to prescribe methadone for patients to pick up at a pharmacy. The bipartisan Modernizing Opioid Treatment Access bill, introduced in the Senate and the House last month, would do just that, dramatically expanding access.

Second, the federal agency that regulates opioid treatment programs (the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) should adopt its recently proposed rule changes without delay. These changes would give patients more flexibility to take home methadone in the course of treatment.

For those concerned about misuse in this context, we can look at evidence from the past two years. To reduce COVID-19 transmission, patients in opioid treatment programs were temporarily allowed to take home more doses. We did not see a subsequent rise in methadone overdoses, in large part because addiction experts at these programs exercised discretion in deciding which patients would benefit from flexible treatment.

Unsurprisingly, clinicians were better at delivering personalized, patient-centered care than one-size-fits-all federal regulations. Like insulin and many other medications, methadone requires close monitoring and dosing changes when patients start using it. Some patients also benefit from additional oversight, such as urine drug testing, to ensure methadone is not misused. Board-certified addiction specialists have completed additional training and are well-equipped to address these challenges.

More than $54 billion of national opioid settlement funds will soon be funneled to states, counties, municipalities and tribal nations across the country. One of the core strategies for distributing these funds is to increase access to addiction medication. Under the current methadone rules, this money can only go so far.

None of us would accept a status quo for cancer or heart disease in which arcane regulations bar patients from the most effective treatment. The 6 million Americans living with opioid addiction deserve no less.

Ashish Thakrar is an internal medicine and addiction medicine physician in the National Clinician Scholars Program and associate fellow of the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania. His research and patient care focus on treatment for opioid use disorder.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.