Opinion: New Alzheimer’s drugs are costly and controversial. Are we going about this all wrong?

The Food and Drug Administration’s recent approval of new Alzheimer’s drugs sparked a flicker of hope for the millions affected by this devastating disease. But this progress casts a puzzling shadow.

The drugs come at a high cost for relatively limited benefits, offering only a brief respite in the pace of cognitive decline. This reality raises a question: Are we fixated on such marginally effective treatments at the expense of more promising preventive measures?

The pharmaceutical industry stands to profit substantially from these drugs, which promise to bring in billions. Eli Lilly’s stock price jumped 6.7% after it announced positive results from a trial of one new Alzheimer’s drug, increasing the company’s value by more than $25 billion that day. This isn’t surprising given that Alzheimer’s disease is estimated to be a $500-billion problem today and, due to our aging population, projected to double in cost by 2050.

Despite the market and media frenzy around the new drugs, their efficacy is contested. When another Alzheimer’s drug, aducanumab, was approved in 2021, three scientists resigned from an FDA advisory committee over the lack of evidence of its efficacy. The role of the drugs’ main target, the amyloid plaques associated with the disease, continues to be disputed.

Beneath the facade of these pharmaceutical victories, however, the potential of prevention remains vastly untapped and underreported.

FDA controversy over a fast-tracked drug carries a lesson.

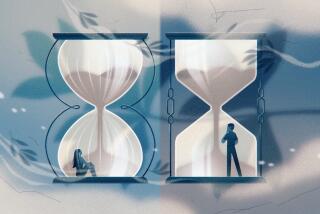

The prevailing Alzheimer’s narrative, perpetuated by the dearth of effective treatments, is of inevitability: The disease is seen as an unstoppable force. This perception overshadows preventive strategies that are not only affordable but effective. Prevention can offer years of cognitive health, not just fleeting months of slowed decline.

Humpty Dumpty is an apt analogy here: It’s easier to prevent his great fall than to put him together again after he’s broken. Similarly, preserving brain cells while they are healthy is far more feasible than attempting to regenerate them after they and their myriad interconnections have been lost. Indeed, these two approaches — prevention versus late-stage reversal — don’t even fall within the same realm of difficulty.

The bias against prevention reflects a larger problem within our biomedical-industrial complex, which predominantly manages disease instead of promoting health. The American healthcare system, which consumes nearly a fifth of all expenditures, is reactive and lucrative, rushing to patch up problems after they arise rather than actively addressing risks. It’s designed to highly compensate years of sick life but not healthy life.

We champion a healthcare system focused on extending health over responding to disease. In addressing Alzheimer’s, this translates into prioritizing prevention strategies that can preserve cognitive health at a fraction of the cost of late-stage drug interventions.

The Food and Drug Administration’s contentious approval of a questionable Alzheimer’s drug is taking another hit.

But what does prevention entail? There are several often-overlooked precautions that can play a crucial role in preventing dementias such as Alzheimer’s.

These include maintaining brain oxygenation, ensuring sufficient intake of certain nutrients, managing stress, limiting inflammation, minimizing diabetes, avoiding head injuries, reducing air pollution exposure, treating hearing impairments, maintaining a healthy weight, keeping our minds active and fostering robust social connections.

This is often a matter of straightforward and cost-effective or even free interventions. Regular aerobic exercise enhances cardiovascular health, promoting efficient brain oxygenation. One study found that people who ate diets rich in phosphatidylcholine, a component of biological membranes that is abundant in eggs and other foods, were 28% less likely to develop dementia. Ensuring adequate levels of vitamin D, a deficiency of which has been associated with dementia, can be as simple as spending time outdoors absorbing sunlight.

Lifestyle modifications like quitting smoking and moderating alcohol consumption can also help significantly. So can reducing hypertension through medication or lifestyle changes. Eating a balanced diet, getting enough sleep and avoiding chronic infections can keep inflammation under control.

Though the impact of each of these practical, affordable measures might be modest on its own, they can work together to delay cognitive decline for years.

U.S. health officials have approved a new Alzheimer’s drug that modestly slows the brain-robbing disease

The effectiveness of prevention-based strategies has been shown in studies such as the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability, commonly known as FINGER. The landmark trial involving more than 1,200 people has significantly outperformed any drug trial to date by tackling dementia prevention from multiple angles, ranging from nutrition and physical activity to mental and social stimulation.

After two years, the group assigned to the prevention strategies did 25% better than the control group on an assessment of overall cognitive performance. Specifically, participants showed improvements in executive functioning and processing speed, key cognitive functions often affected early in Alzheimer’s disease. They also experienced broader health benefits; the side effects of prevention are often positive rather than negative.

The success of the FINGER trial has inspired a new wave of research, with several countries now conducting their own versions, including the U.S. Study to Protect Brain Health Through Lifestyle Intervention to Reduce Risk, or POINTER. The global scientific community is recognizing the value of prevention.

The fight against Alzheimer’s is at a critical juncture. Prevention and treatment should be seen not as mutually exclusive but rather as facets of a comprehensive approach to this formidable disease. But the emphasis we place on each path has far-reaching implications not only for the millions directly affected but also for the trajectory of our healthcare system.

While it remains crucial to continue developing innovative treatments, we have at our disposal a range of accessible and cost-effective preventive measures bolstered by scientific research. These measures will not drain our pockets but will require us to recalibrate our lifestyles and priorities.

Individuals as well as healthcare providers, policymakers and society need to redirect more of our focus and resources to Alzheimer’s prevention. This could save billions in healthcare costs and, more important, preserve the memories and identities of countless individuals for longer.

In a world where Alzheimer’s is a growing threat, we can write a different narrative in which the disease is less of an inevitability and more of a challenge, one we have the tools to combat. Let’s ensure that we have as few afflicted loved ones as possible.

Nathan Price is the chief scientific officer of Thorne HealthTech and a professor on leave from the Institute for Systems Biology. Leroy Hood is the chief executive of Phenome Health and a co-founder and professor at the Institute for Systems Biology. They are the authors of “The Age of Scientific Wellness.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.