Opinion: How Susan Love changed medical care for breast cancer patients

- Share via

In the end, a lowly tape recorder helped to change the face of breast cancer treatment.

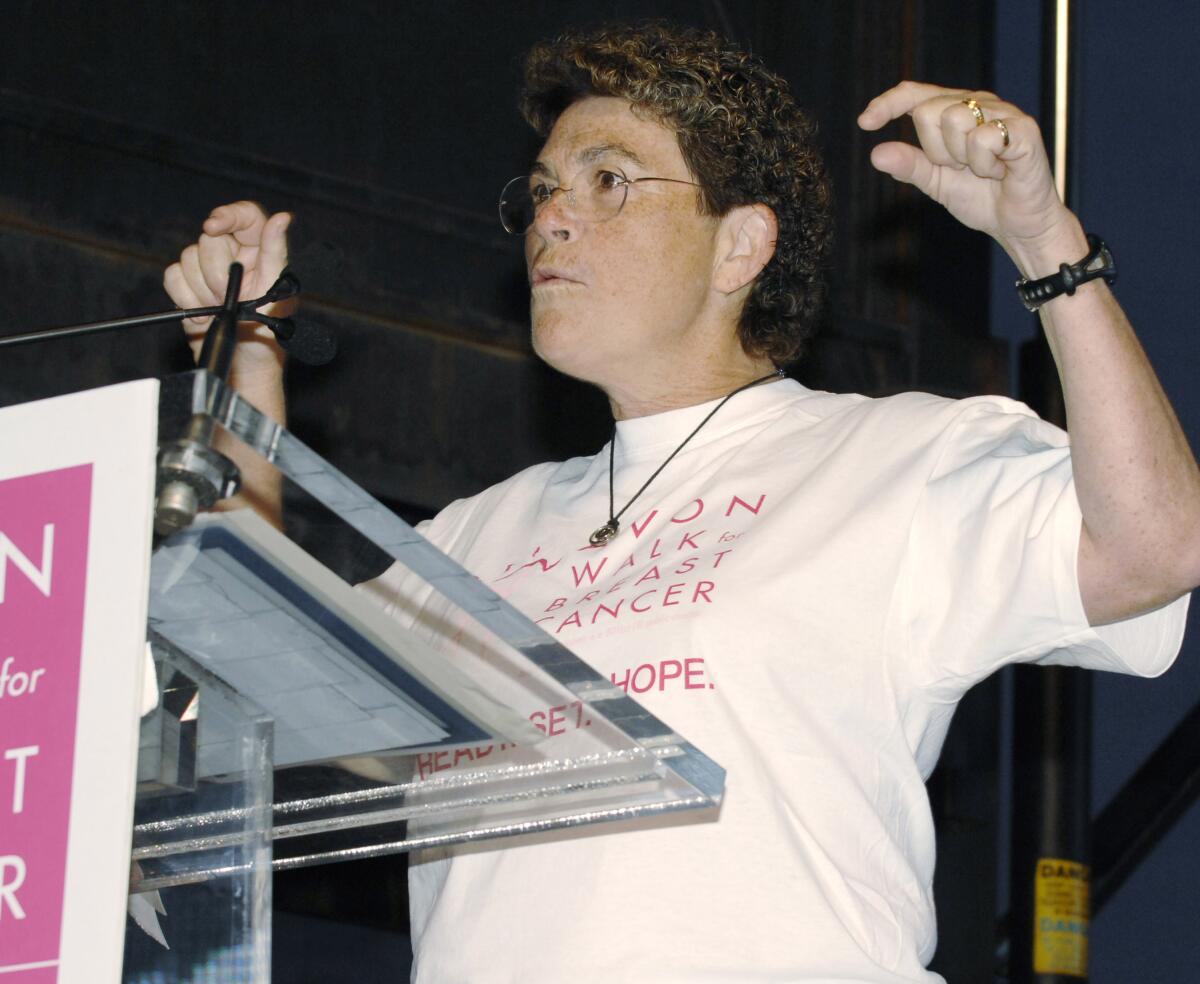

Susan Love, who died Sunday at age 75, was in the early 1990s the director of the UCLA Breast Center, which was designed to turn the world of breast cancer treatment on its head.

The one advantage to not being part of the old boys’ medical network, Love liked to say, was that she didn’t have to play by its rules. So she created a program that had as much to do with patient care, with what went on inside the exam room, as it did with larger policy issues.

She offered a tape recorder and tape to every new patient — because in her experience, she joked, a woman’s ears stopped working as soon as she got a diagnosis of breast cancer. She could listen to the tape at home, if she forgot details that had been hard to process. And when well-intentioned family members and friends asked too many questions, Love advised patients to hand them the tape and go to the movies.

Dr. Susan Love encouraged patients to take an active role in their care and created a comprehensive guide to breast cancer long before the internet.

That was her considered professional advice: Go to the movies. She didn’t want a patient to think of herself as an uppercase “Patient,” but as the same person she’d been before her appointment, except that now she had a medical challenge to meet.

Love rejected the standard protocol that had a patient running all over town, her X-rays in her bag, seeing one specialist after another and waiting for them to talk and get back to her. At the UCLA center, a patient spent the afternoon in an exam room, as one specialist after another came to see her. After that, the doctors sat together to generate a treatment plan, which made little sense in terms of the economics of medical practices, but all the sense in the world for the care of patients.

Experts in the field extol her contributions to research and treatment. Activists, like her colleague and friend, National Breast Cancer co-founder Fran Visco, can speak to her indomitable spirit. But the little stuff — the tape recorders, the jokes, the affection she had for her patients — that I saw in the 15 months I followed her for my book on breast cancer had an impact on clinical practice that resonates today.

Love’s insight, according to Visco, was this: “She knew that women could understand the complexity of breast cancer and use that knowledge to make their own, informed decisions about their health.”

It’s hard to overstate what a radical perspective that was, only 30 years ago. But in fact too many active, capable women showed up for their medical appointments feeling suddenly lost, subsumed by their diagnoses.

Love set out to change all that, and the tape recorders were just the first step. She urged patients to appoint an advocate, one of those attentive family members or friends, to attend appointments, be around if surgery was required, be the chauffeur for radiation sessions. A patient needed a designated companion to tackle logistics — and if she didn’t have one, Love’s staff included people who could step in to help.

She tried, whenever possible, to be at a patient’s side as anesthesia was administered, at a time when many surgeons waited to enter the operating room until a patient was unconscious.

She tried as well to be the first voice a woman heard when waking up in recovery. But there was more, as I learned when I observed her in surgery: Once the operating room staff was assembled, but before she began a procedure, she had everyone take a silent moment together, out of respect for the woman on the operating table, and for the magnitude of what was about to happen.

Love was too outspoken for some, with her talk of “slash, burn and poison” to describe traditional treatments, and her reference to extensive surgeries as “amputations,” but she never backed down. And as evidence mounted supporting her position, she was able to guide patients toward less drastic options.

She mixed a profound empathy with a steely, activist will, and in doing so tipped the power balance in favor of women. Any woman who walks into a doctor’s office today with pen and paper in hand, or her phone’s voice memo app turned on, is a beneficiary of Love’s pioneering efforts.

Karen Stabiner is the author of several books, including “To Dance With the Devil: The New War on Breast Cancer.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.