Opinion: We need King’s message as much today as in 1965: ‘How long? Not long’

President Kennedy once posed the question: What is it to be an American today when our people are divided as never before? Now as then, too many of us have lost our way, our will and our sense of historic purpose. The good and righteous in us knows what’s necessary for a renewal. For a healing. For a reclamation of the most important values that have eluded us, but still define our journey as human beings: freedom, democracy and equality of opportunity. The problem is we don’t know where to go, or we’re too afraid of how we get there.

So many Americans struggle to get beyond MLK 101: the non-threatening King of August 1963 on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. His challenge to America goes much deeper.

Nov. 7, 1978. I was 10 years old when my father, the headmaster of my Brooklyn independent school, woke me up one morning and told me that school was canceled. Instead, we would be marching over the Brooklyn Bridge in the name of Black solidarity. This would be my first protest, and while I found the cause important — a Crown Heights civic leader, a Black man named Arthur Miller, had been killed by police, and the officers were cleared of all blame — I was scared.

In school, my classmates and I read with horror about the marchers, led by the Rev. Martin Luther King, who’d walked for five days and 54 miles only to be beaten and bloodied by police as they crossed the Selma bridge. I was terrified, and, in my juvenile mind, Mayor Ed Koch’s racist policies that I’d heard about at the dinner table and read about in Black News magazine almost ensured that the bridge would be opened up while we were on it and we would fall into the East River. So, I refused to march. Damn freedom and democracy. What good would they be if I were dead? Surely, there had to be a better way to protest.

When states ban antiracism history from schools, they’re disavowing what King stood for

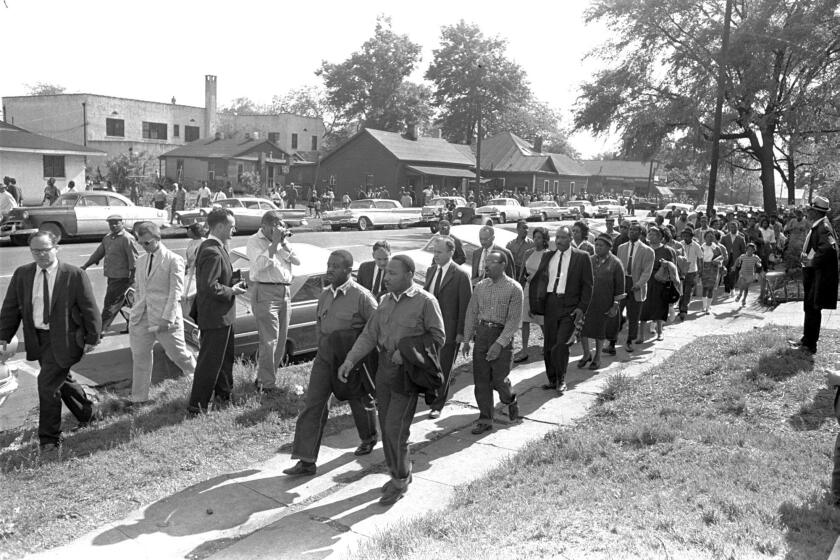

Most people know the speech that King delivered at the end of the Selma-to-Montgomery march, on a flatbed truck, as the “How long? Not long” speech because that’s the memorable refrain he chanted five times to quell the frustration of our being sick and tired of being sick and tired of waiting for justice. This was King as blues musician, preaching a naïve, if not hopeful, optimism.

The actual title, at least according to some scholars, is “Our God Is Marching On.” Regardless of what we call it, its purpose is clear and indefatigable. King’s words are meant to encourage us, to comfort us, to restore our confidence that victory is inevitable. King amplifies Maya Angelou’s words, “We may encounter many defeats, but we must not be defeated,” and elevates its message with a divine calling for the civil rights movement, that in the difficult and challenging moments of protest, in the frustrating hour, let us remain committed to struggle. That we are on the move and no wave of racism can stop us. That the road ahead is not altogether a smooth one, but we must keep going.

Easier said than done.

Martin Luther King Jr. understood that the official power of the state to punish and murder Black people was fatal for a democracy.

My mother pulled me from under the kitchen table, or dragged me from the closet, I don’t remember, but my parents had determined that I was going to the march. That I would make the trek with my classmates and community over the Brooklyn Bridge — which by the way, does not open, Kwame, my mother had said, laughing, while I cried a river.

Our demonstration started at the House of the Lord Pentecostal Church on Atlantic Avenue, about a thousand of us, led by its pastor, the Rev. Herbert Daughtry. As we neared the Brooklyn side of the bridge, my heart sped, my feet tired, and my soul bled. I was frozen in fear. But being near the front of the line, I was forced to keep moving. I could see my end, a horror I’d never faced. And, then as we crossed over, eye-to-eye with policemen in riot gear on horses, with barking dogs, with impending doom, the pastor began to melodically and emphatically sing these words: We’re fired up, we can’t take no more. We’re fired up, we can’t take no more. And something happened in me. Something that propelled me forward.

I stood on that bridge, and before I even knew what I was doing, I sang along. And, I stopped crying. The sight of police batons didn’t faze me anymore. The scowling dogs no longer alarmed me. A set of simple words had done that. I couldn’t articulate it then, but I did not feel alone anymore.

In the ’90s, as a student at Virginia Tech, I would use my words to speak the truth about the vestiges of racism on our campus — fraternities Halloweening in blackface — and around the world — apartheid, the institutionalized system of white supremacy in South Africa. I was on the move to the land of freedom, and as King had challenged, I would not get weary. Decades later, when police brutality would kidnap the American dream, turn it into a recurring nightmare for brown and Black boys being blown away like sand in a windstorm, human beings across the globe would heed King’s directive to walk together, children, because we could not allow these travesties to become “normal.”

Between the covers of the Rev. Martin Luther King’s bold speech, there flows a big sea of possibility and promise. In this soft symphony of hope, each line echoes a booming bass of vision. In the war room of our red, white and weary blues, we become pioneers in this renewal by awakening our conscience, summoning our courage, then treading the stony road through a tunnel of hope. Or, as Dr. King put it: Our God is marching on. And so must we.

Kwame Alexander is the producer of “The Crossover” and the editor of “This Is the Honey: An Anthology of Contemporary Black Poets.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.