Editorial: L.A. is now paying the price for the tough-on-crime era

- Share via

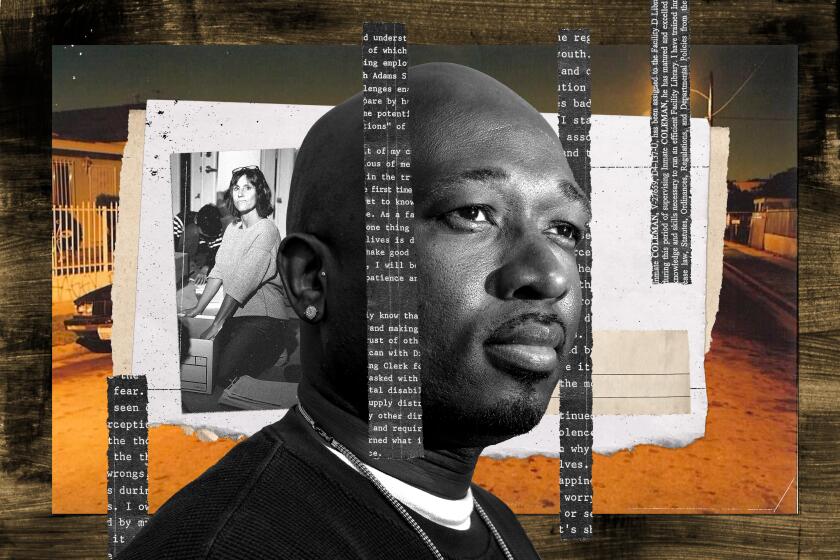

A day after being cleared of a crime for which he served 20 years in prison but did not commit, Jofama Coleman was asked Wednesday how he felt about the legal system that prosecuted, convicted, sentenced and imprisoned him.

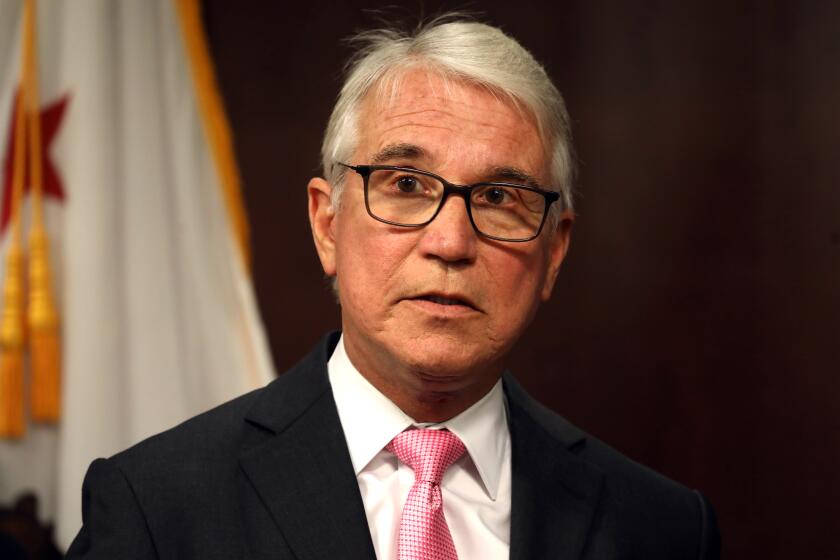

Coleman considered the question for a moment as he stood alongside co-defendant Abel Soto, who was exonerated in January after also losing two decades to prison. With them was their lawyer, Ellen Eggers, and Dist. Atty. George Gascón, whose office has now cleared 10 people who were wrongly convicted and imprisoned.

The wrongful conviction and imprisonment of Maurice Hastings for nearly four decades underscores the justice system’s responsibility to be careful when prosecuting defendants and the importance of reopening cases when exonerating evidence appears.

Coleman said he was at first resentful. But then a supposed eyewitness who testified against him acknowledged that he never actually saw Coleman at the wheel of a white van used in the deadly shooting of 16-year-old Jose “Chino” Robles on May 10, 2003. Testimony that Soto fired the fatal shots was similarly rejected.

“It wasn’t until one of these individuals grew up and developed a conscience, or whatever it may be, and actually told the truth,” Coleman said, that he could begin to make peace with what happened.

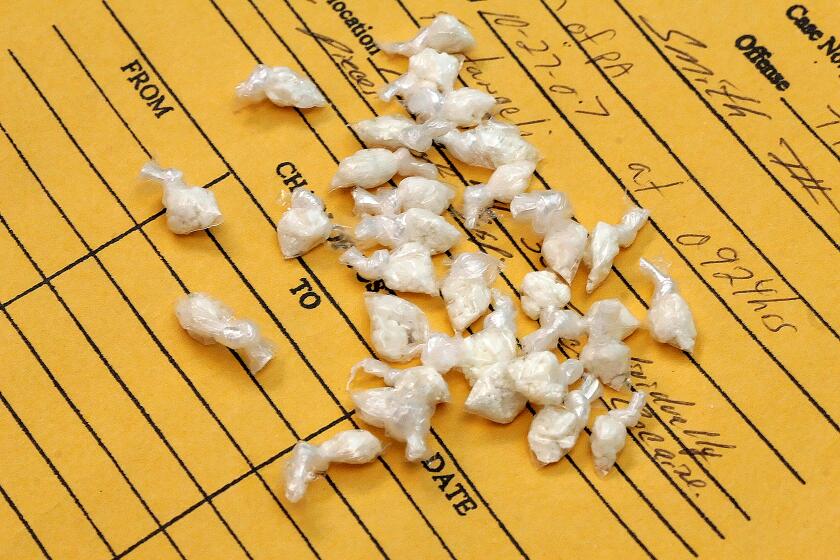

America responded to the 1980s crack epidemic with police and prisons instead of public health. Now look where we are.

Robles was one of thousands of victims of Los Angeles’ cruel street gang warfare in the 1990s and early 2000s. Coleman and Soto were likewise victims, not of killers but of sloppy if earnest police work and prosecution, and the tunnel vision of L.A. officials who were so adamant about cracking down on crime that they punished the wrong people. Very few, like Coleman and Soto, have won their release. Many likely remain unjustly imprisoned.

How did it happen? A few cops may have been corrupt. Los Angeles Police Department Officer Rafael Perez comes to mind, along with others who planted evidence and framed suspects in what became known as the Rampart scandal. Some prosecutors may have known they were trying innocent people. But the vast majority undoubtedly believed they were working hard to bring killers to justice and peace to the victims’ loved ones. They felt enormous pressure from elected officials, who felt enormous pressure from voters and constituents to stop the killing. In their zeal, they may have cut corners, or succumbed to prejudices about people they were convinced — incorrectly — were guilty.

The two men were convicted of a murder they did not commit. But how could they prove their innocence from behind bars? How could they be exonerated without help?

Franky Carrillo Jr. was tried, convicted and imprisoned under circumstances remarkably similar to Coleman’s and Soto’s. Witnesses testified that they saw Carrillo fire the murder weapon in a fatal 1991 drive-by. They were encouraged to do so, despite their misgivings, by investigators misusing ID photos in books and so-called six-packs. Nearly two decades later, they recanted.

Eggers, the same defense lawyer who helped to get Coleman and Soto cleared, worked with the Northern California Innocence Project to win Carrillo’s 2011 release and exoneration. Carrillo is now a county probation commissioner and an Assembly candidate in Tuesday’s election.

Giovanni Hernandez and Miguel Solorio were both convicted of murders they said they had nothing to do with as teenagers. Their efforts to be exonerated finally came to fruition on Wednesday.

“The Innocence Files,” a 2020 Netflix documentary series, examined Carrillo’s harrowing journey. Sheriff’s deputies, prosecutors and purported witnesses who at first were depicted as heroes later look like villains. Of those, a few — the ones who recognized their mistakes and the harm they caused, and who worked to repair it — became heroes again.

Our society is somewhere on that same path. We overbuilt our prison system and then overfilled it, too often carelessly. We failed to meet the scourge of violence with more constructive investments to deter crime. We continue to permit law enforcement to use unreliable techniques and technologies to solve crimes. We too often respond to crime spikes (mere blips compared with the violence of three and four decades ago) by rolling back hard-won criminal justice reforms.

If you thought there were a lot of news stories last year about wrongfully convicted people finally getting justice, well, you were right.

It’s time for our society to do what Coleman said the false witness against him eventually did — grow up and develop a conscience. That means supporting communities battered by crime with better education, employment opportunities, healthcare, even street lighting, and not just police and prison. It means atoning for past mistakes by insisting that every county, every state, the federal government, build up their conviction integrity and habeas corpus operations, as Gascón has done, to bring innocent victims of overzealous prosecutions home.

“There is significant danger that comes with convicting the wrong person,” Gascón noted Wednesday. There is the unimaginable loss suffered by people wrongly locked away, and the families that had to live without them, the stain on a justice system we tout as the world’s best, and the false justice given to crime victims.

Gascón’s final point should catch the attention of every tough-on-crime adherent:

“It also leaves the true perpetrators free to inflict further harm upon the community.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.