Editorial: Religious freedom under attack in Oklahoma schools

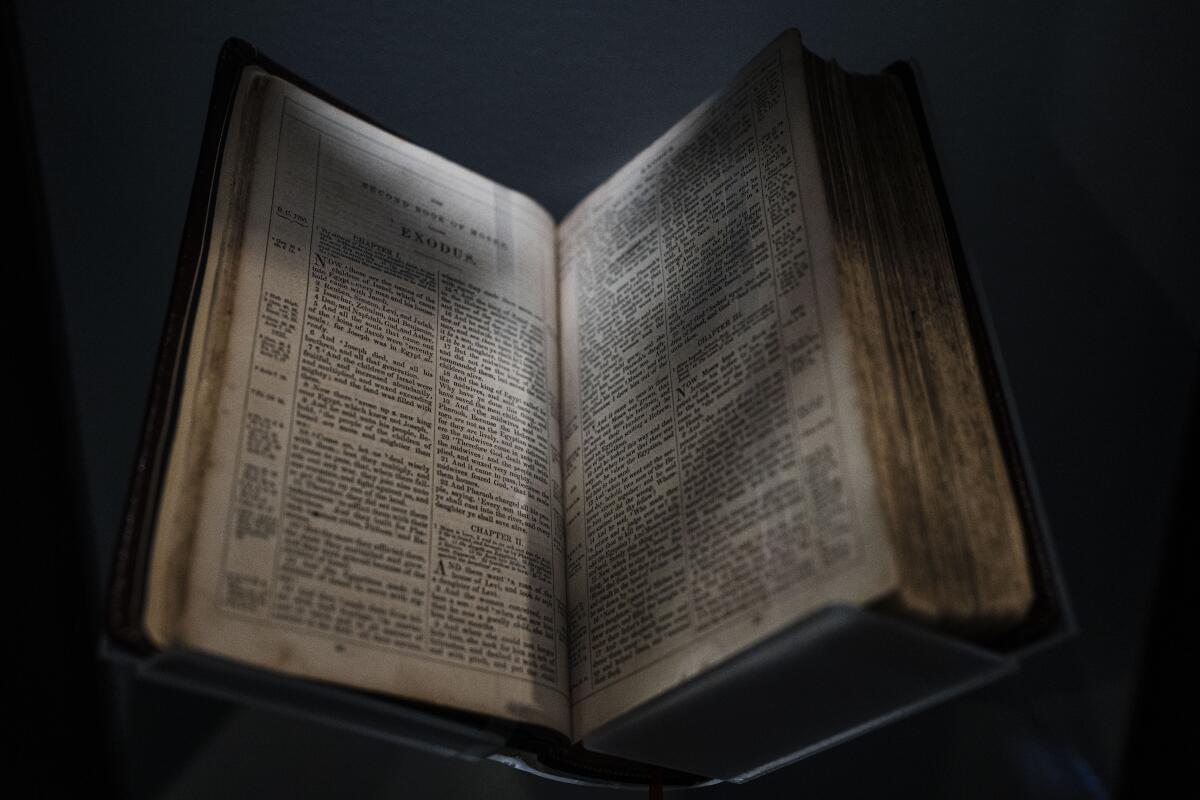

For people who supposedly revere the Founding Fathers, some Christian conservatives seem to have no problem ignoring one of their most abiding principles: the separation of church and state. Now the chief of schools in Oklahoma is demanding that all public schools teach the Bible from grades 5 through 12, saying it is necessary for an understanding of the country’s history. It is more of an attempt to ignore much of that history.

The Bible can have a valid place in public school classrooms. In a 1968 case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that although the daily Bible reading in Pennsylvania schools was an unconstitutional effort to inculcate religious teachings, the Bible can be a part of the lesson plan “when presented objectively as part of a secular program of education.”

Literature, for example, is full of biblical references. How could students understand John Steinbeck’s classic, “East of Eden,” if they aren’t familiar with Eden or the story of Abel and Cain? Shakespeare’s plays are filled with biblical references. Comparative religion classes are another appropriate place to visit the Bible in public school; the AP World History course includes a unit on world religions.

Louisiana’s law seeks to infuse a specific brand of Christianity into public institutions — and to uproot rulings against the propagation of religious teachings.

But that’s not what’s happening in Oklahoma — where, by the way, teachers already were free to use the Bible if it was relevant to an objective or secular lesson. In a memo, state Supt. of Public Instruction Ryan Walters said that the Bible and Ten Commandments must be taught in the classroom because of “their substantial influence on our nation’s founders and the foundational principles of our Constitution.”

While he didn’t say it explicitly, Walters’ language strongly implies the very thing that the 1st Amendment sought to prevent: that the United States be governed as a Christian nation. It is certainly the predominant faith in the country, but the Constitution prohibits religion from being imposed on others by popular vote or political mandate.

First they came for abortion rights. Then a judge in Texas said insurers didn’t need to cover HIV-prevention drugs.

In his new guidelines for teachers, Walters goes out of his way to repeat wording about using the Bible only in the context of literature, history, art and so forth. But his guidelines call for teachers to use it for close literary analysis of writing. It certainly makes for an unusual choice over the genius of Fyodor Dostoevsky, Ernest Hemingway, Maya Angelou and the like. Because teachers have limited teaching time, the mandate pushes out great works of literature and the consideration of great cultures that are not Western.

The careful wording can’t mask what is clearly an effort by Christian conservatives to blur the line between church and state in the classroom, especially in a country that is growing in religious diversity. It goes alongside the Louisiana governor’s recent order to place the Ten Commandments in public schools and a recent decision by Oklahoma’s state board to approve a Catholic charter school. Charter schools are privately operated but publicly funded, and the state Supreme Court rejected the use of taxpayer money for a religious school.

Expect more moves to bring Judeo-Christian religion into schools. It is unclear, given recent U.S. Supreme Court rulings, whether today’s court majority will honor the wise precedents that preserved Thomas Jefferson’s “wall of separation” between church and state intact. The current wave of Christian nationalism should, if anything, prod the justices to keep that wall as strong and clearly delineated as their predecessors did.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.