A queen of horror delivers more delightfully twisted stories

Book Review

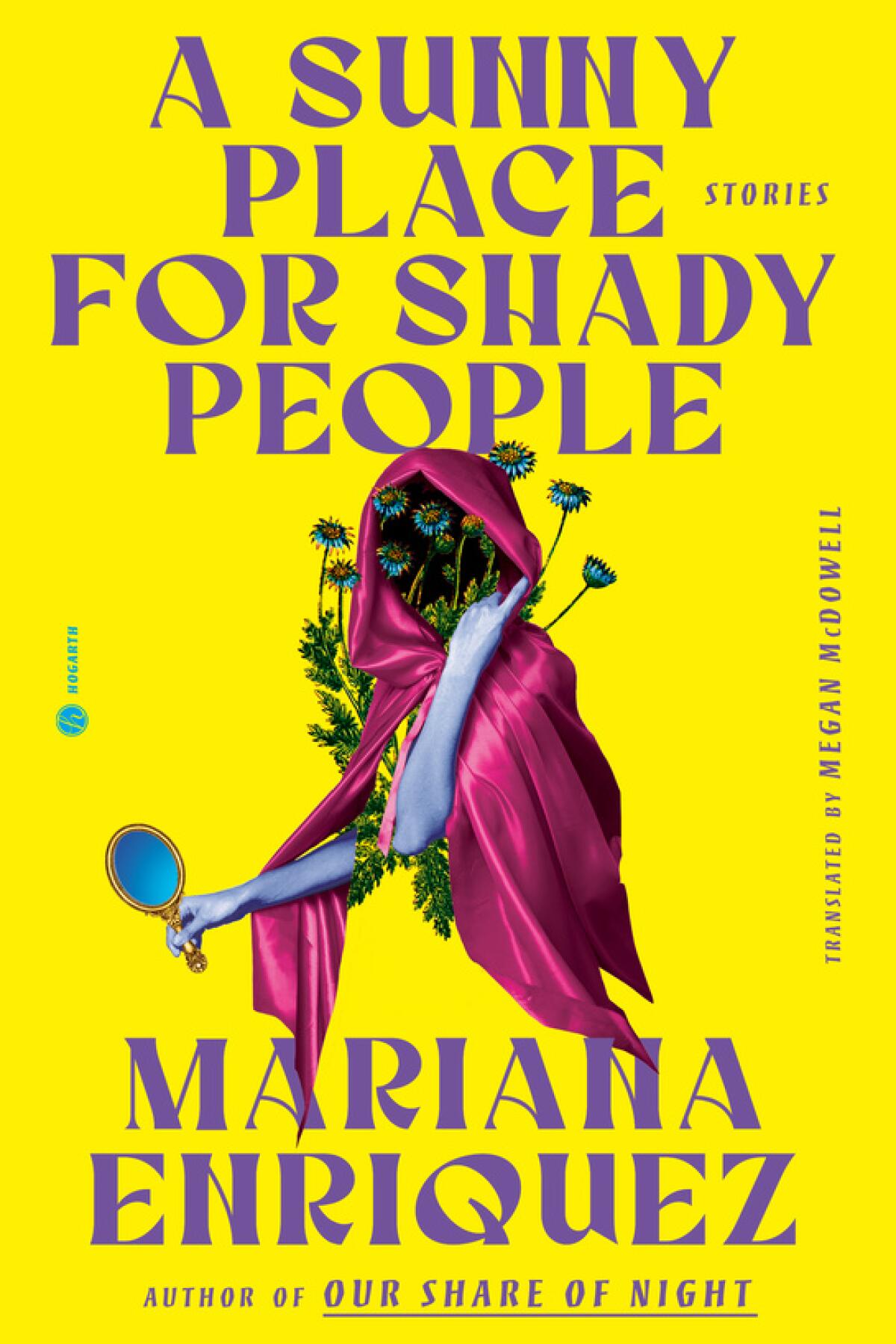

A Sunny Place for Shady People

By Mariana Enríquez. Translated by Megan McDowell

Hogarth: 272 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Critics have called Argentine writer Mariana Enríquez a queen of horror, and since the publication of her gorgeous, monstrous novel “Our Share of Night,” fans have turned her into a literary rock star. Her new short story collection, “A Sunny Place for Shady People,” delivers another striking performance.

Told mostly in first-person by female narrators, these 12 stories take place in Argentina, with a foray abroad to Los Angeles. While Enríquez revisits themes from her previous work — sexism, illness and the cruelties of class inequality — the sharp focus on mental, physical and economic ruination in this collection, which was originally published in Spanish in March, feels distinctly post-pandemic. Perhaps the last few years have brought reality more in line with the horror genre. Entertaining, political and exquisitely gruesome, these stories summon terror against the backdrop of everyday horrors.

Enríquez has described her sensibility as retorcida — twisted. She draws inspiration from a wide spectrum of influences, including viral videos, Tupí-Guaraní myths, popular roadside saints, urban legends and the Argentine dictatorship of the 1970s and ’80s.

The eponymous story is set in post-pandemic Los Angeles. An Argentine journalist travels to the infamous Cecil Hotel to observe a ritual. The participants believe they can summon the spirit of Elisa Lam, who in real life disappeared in early 2013; her body was found in a hotel water tank a few weeks later. During the investigation, the police released security footage that showed Lam behaving unusually in the hotel elevator. The video went viral.

“It’s legendary, an internet classic,” the story’s narrator says. She’s crude, as unredeemable as any of us millions who watched the video out of morbid curiosity. Enríquez, a culture journalist, has much to say about the nature of fandom; in a recent nonfiction work she relates her obsession with the British band Suede. Here, she illustrates the macabre fandom that arises around a shocking, unexplained tragedy. The ritual manages to summon something into the water tank. An “answer” comes from beyond the veil — but is it what we wanted?

Readers can’t go to Enríquez looking for closure. The retired doctor in “My Sad Dead” helps soothe and banish her neighborhood ghosts, but they always come back: “It’s as if they forget, and we have to start all over again.”

In Kailee Pedersen’s debut, generational pain and malice rule the narrative, with elements of the supernatural woven in.

This is Enríquez’s labyrinth. There are no exits. In “Face of Disgrace,” a woman tries to break a multigenerational family curse that began with a rape. She believes that telling her daughter about the curse — dragging the truth into the light — will dispel it. As the curse erases her facial features, she runs blindly toward her daughter, and a tremendous fear strikes her, as she “didn’t know whether telling her daughter everything was going to be the end or just another mocking laugh…just another trick like the feet whose footprints always led somewhere else, far away from their owner.”

“A Sunny Place for Shady People” lacks the thoroughly imagined lore of Enríquez’s 600-page novel “Our Share of Night,” which centers on a power-hungry cult and its worship of an all-devouring darkness. But Enríquez still manages to suffuse these stories with a sense of place, politics and history. “Hyena Hymns” takes us to a haunted mansion once used as a torture center by the Argentine dictatorship. In “A Local Artist,” tourists visit a ghost town whose abandoned women have been saved by a bizarre “baby.” “The Refrigerator Cemetery” is set in a deserted factory that the army used for weapons storage and became the site of a woman’s unspeakable crime.

Feminism and queerness are foundational aspects of Enríquez’s work. In “Metamorphosis,” a woman has a hysterectomy and several fibroids removed. She decides to keep one — described as “a pale pink egg of flesh, irrigated with veins,” “a hormonal ginger root” and “a fat mandrake.” It’s not a baby, she insists, but still she created it. Why let the hospital throw it away? She decides to have it reinserted through a unique body modification. The reunion with her fibroid — an experience that she describes as “very gentle and very clean” — is more healing than her traumatic hysterectomy was. In the world of this collection, it’s a happy ending.

Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s ‘Silver Nitrate’ continues her tradition of overturning genres — this time in the chilling story of film horror fanatics in Mexico City.

Enríquez’s writing, translated by Megan McDowell, is engrossing. I couldn’t turn away from some of the tactile descriptions, including “nails were eaten away as if he had termites under his cuticles.” The humor is dark: “the tantrum of a woman who just had a hysterectomy” (a pun on “hysteria”). Her imagery is often sickening, perfect. In one story, a container of milk rolls down the front steps of a house and explodes pink — a symbol for the gruesome double homicide that has happened inside.

Across their morbid tapestry, these stories also invoke other writers, music, fashion and the arts. The collection includes epigraphs from Thomas Ligotti and Cormac McCarthy; characters refer to “Game of Thrones,” a Michael Myers mask from the “Halloween” movies, and Taylor Swift. “Night Birds,” which echoes Shirley Jackson, was written for a 2020 exhibition of Argentine artist Mildred Burton’s work. “Julie,” about a young woman who claims to have sex with ghosts, ought to be paired with Marjorie Cameron’s 1955 drawing “Peyote Vision” of a woman having sex with a demon. And “A Local Artist” includes descriptions of paintings so unsettling that I longed to see them.

Enríquez has numerous works that remain untranslated from the Spanish, including novels, novellas and a nonfiction exploration of cemeteries. “A Sunny Place for Shady People” makes yet another argument to bring more of that work to a wider audience. If we seek justice, redemption, freedom in Enriquez’s stories, we’ll be gutted; her characters are lucky if they survive. But we are lucky to be privy to their strange and mesmerizing journeys.

Gina Isabel Rodriguez is a fiction writer and essayist. The daughter of Chilean immigrants, she is revising a novel set during the Pinochet dictatorship.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.