Trump’s defense of a neo-Nazi rally crossed a line for many Republicans. What will they do about it?

Reporting from Washington — It took President Trump’s defense of a neo-Nazi rally for many Republicans in Congress to publicly distance themselves from the White House, after months of brushing off his impolitic behavior and tweets.

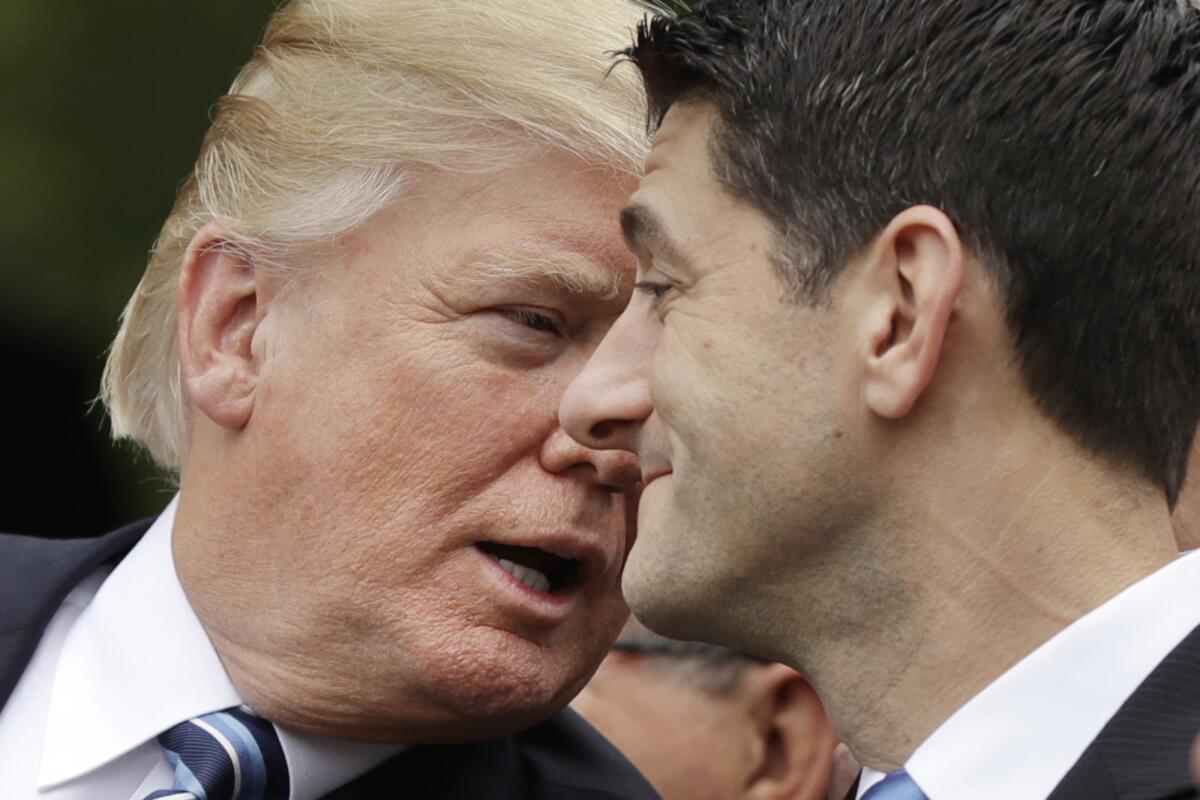

House Speaker Paul D. Ryan said white supremacist bigotry is “counter to all this country stands for.” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said, “There are no good neo-Nazis,” an apparent reference to Trump’s claim that there were some “very fine people” among the torch-carrying white supremacists in Charlottesville, Va., last week.

Rank-and-file Republicans churned out statements backing away from Trump, and outspoken voices in the party began wondering aloud Wednesday whether Republicans still carry the mantle of the party of Abraham Lincoln.

“We can’t claim to be the party of Lincoln if we equivocate in condemning white supremacy,” tweeted Sen. Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.).

After Trump’s remarks drew a thank-you tweet from former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) sounded off.

“Many Republicans do not agree with and will fight back against the idea that the party of Lincoln has a welcome mat out for the David Dukes of the world,” Graham said.

But the GOP-led Congress isn’t expected to respond with much more than impassioned statements and social media posts.

Though Democrats and others quickly urged Republicans to follow up their words with actions — ranging from a resolution stating that Congress does not embrace white nationalism to a more wholehearted censure of the president — such moves seem unlikely.

Few Republican lawmakers stand willing to criticize Trump by name for his insistence that the white nationalists rallying in Charlottesville and the counter-protesters opposed to racism were equally to blame for the violence that erupted.

Most tried to stick to their schedules during the August break, visiting constituents and job centers back home.

But after struggling for months to figure out how best to handle Trump, many are finding it harder to just ignore him.

“A line’s been crossed, and no one wants to be seen as supporting white nationalists’ vision of America,” said Pearson Cross, an associate political science professor at University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

“On the other hand, they’re caught in a bit of a bind because it’s their president that’s putting them in this position,” Cross added.

A line’s been crossed, and no one wants to be seen as supporting white nationalists’ vision of America.

— Pearson Cross

Trump remains popular in many states and congressional districts that elected Republicans to the majority in Congress, despite his sagging approval rating nationwide. Lawmakers remain reluctant to put themselves crosswise with the voters many will need in next year’s midterm election.

Moreover, Republicans in Congress have hitched Trump’s popularity — which stems in part from his disruptive and racially tinged tone — to their legislative agenda. It was a decision cast last year when GOP lawmakers rallied around Trump as their nominee for president.

“As long as Trump remains popular with their primary voters, I don’t see things changing,” said Doug Heye, a former spokesman for the Republican National Committee and GOP leadership in Congress. He did not support Trump’s presidential bid.

For a party that has labored to expand its base of white voters into the growing electorate of Latino and other minority groups, many saw an irreparable turning point.

Here’s who quit two of Trump’s business advisory councils and when »

“After that Trump press conference, I don’t know how I can tell any minority why they should vote Republican,” Heye wrote on Twitter.

Former House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, the highest-ranking Jewish Republican before he was kicked out of office by a tea party challenger, acknowledged an irreconcilable split.

“I think that the party is President Trump’s party now,” Cantor told the Washington Examiner.

Republicans have stood by Trump before — when he said some Mexican immigrants were rapists, bragged about grabbing women’s body parts and strove to end the FBI probe into Russian interference into last year’s presidential election.

Even McConnell, who has recently been the target of Trump’s Twitter scorn over the collapse of the GOP healthcare bill, failed to call out the president by name Wednesday. And he issued a statement only after a Trump-backed candidate won a runoff spot in Alabama’s primary election for senator Tuesday.

But the public backlash to Trump — from the former Bush presidents, celebrities, sports stars and everyday Americans — may eventually force Congress to do more.

Lawmakers could be confronted by protesters at town hall meetings urging Congress to reassert itself as a check on the executive branch.

As the majority in Congress, Republicans could be pressured to hold public hearings on the far-right groups, renounce their personal support for Trump or even call on the president to resign, activists said.

“There’s an imperative right now in the country to make clear Trump is not speaking for the country when he defended Nazis and supremacists,” said Jesse Ferguson, a former top aide to Democrat Hillary Clinton. “The only way to do that is to have the co-equal branch of government say it.”

Others, though, see Trump’s brush with supremacists as the not wholly unexpected coda to the Republican Party’s long courtship of white voters.

As Democrats during the civil rights era started becoming a party increasingly made up of minorities, Republicans courted white voters, often through messages with racist leanings.

Former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort used a Nixonian-like Southern strategy to appeal to white voters when he worked on Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign. Many of the same voters were drawn to Trump, citing his willingness to be politically incorrect.

Racial resentment, as tabulated by the nonpartisan American National Election Studies, was one of the strongest predictors of voter preference for Trump, noted Matt Barreto, a professor at UCLA.

“I feel like we waltz past this all the time,” said University of Louisiana’s Cross. “Explicit embrace of the white nationalist or racist ideology is not something the Republican Party is comfortable with.

“On the other hand, finding ways to appeal to those people who may have racist views, and may vote, has been an art long practiced by Republicans.”

ALSO

Trump wants a border wall, but few in Congress want to pay for it

More coverage of politics and the White House

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.