Efforts to regulate bail companies have some unlikely allies: bail agents

In recent years, the seriousness and number of official complaints related to the bail industry in California have significantly increased while bail agents and bounty hunters face limited oversight, putting vulnerable communities at risk of fraud, embezzlement and other forms of victimization.

This year, as Gov. Jerry Brown has pledged to work with lawmakers in a push to overhaul how courts assign defendants bail and to better regulate bail agencies, even some who profit from the court practice admit it’s time for regulation. These bail and bail-recovery agents could become unlikely allies, saying they advocate for change because they’ve seen the system abuse the poor.

Until now, the loudest critics of the efforts have been bail agents who have filled Capitol committee hearing rooms, blasted legislators on social media and poured more than $600,000 into lobbying efforts to prevent changes to how judges set bail and how their businesses are regulated. Civil rights and criminal justice groups have aggressively fought back against campaigns from the bail industry. One tactic: exposing agents who have faced criminal charges on a public website.

Jane Un, a Redlands bail agent who founded her own company in 2006, believes bail companies have too much power.

There are a number of examples of practices for collecting the bail money that she calls abusive. Agents can use any citation to dock a client for breach of contract, such as arriving a few minutes late to a court appearance. She said clients have told her some agents hold people inside their offices until they or a relative can produce the money owed.

Un got involved in the business after having her own negative experience following a brush with the law. (She was eventually cleared of real estate fraud and conspiracy to commit burglary, public records show.) She has privately reached out to lawmakers about the bad practices she’s seen from bail agents motivated by greed.

Now she’s being more vocal and calling for a change to the system. There are multilayered problems. Un sees her clients struggling from the beginning. When someone is arrested, judges set bail according to county-established fees based on the gravity of the alleged crime. The fixed amounts vary widely and are too high for many families, she said.

Defendants must post the amount up front or pay a 10% fee to a bond company before they are released. Those who can't afford either option may remain behind bars up to an additional 48 hours before they are formally charged and see a judge.

Un has helped petition courts for lower bail amounts on behalf of some defendants, according to court records and her clients — something she says many others in her business don’t do. “Bail agents give [clients] the contract and don’t explain it, and people sign and initial without fully reading or understanding it,” she said.

One of Un’s most recent clients, 28-year-old Araceli Cortes, said a different bail company took $5,250 in payment for her husband’s release, but lied to her and said he couldn’t actually leave because of an immigration hold. Cortes said she checked with the jail and found there was no hold and that the company hadn’t posted the bail. The agents refused to return her money.

Another element of the business under scrutiny: recovery agents and bounty hunters. Many are paid on commission and don’t need to be licensed, meaning they can have insufficient knowledge of search and seizure or other laws of arrest.

Marc Bender is a recovery agent with Aladdin Bail Bonds, one of the largest companies of its kind in the state based on its number of employees. He said many bounty hunters don’t get paid if they don’t bring a person in, meaning “there is a lot of incentive to cut corners.”

Un said she once overheard two bounty hunters that she hired bragging about taking an already stolen Louis Vuitton purse from the client. “I am hearing all of this, and I’m thinking, ‘My god, the bounty hunters I hired are committing a crime and they are getting away with it,’” she said.

She said the most she could do was not hire them again.

Norma Alcala, a West Sacramento school board member who owned her own bail company in the late 1990s, remembers more-severe cases. In the male-dominated industry, she said, agents often did not return their clients’ collateral, things like luxury cars and expensive jewelry, and some were known for demanding “couch bail,” getting someone out in exchange for sexual favors.

She left the business because she saw the rich buying themselves out of trouble while poor people were “the ones who really suffer.”

Gov. Jerry Brown postpones negotiations over legislation to overhaul the bail system in California »

Stories like these have prompted lawmakers to take a hard look at an industry of roughly 3,200 registered agents in California who collectively write about 175,000 bail bonds per year.

Assemblyman Rob Bonta (D-Oakland) and state Sen. Bob Hertzberg (D-Van Nuys) are working to overhaul the bail system.

One proposal would eliminate fixed bail fees and require counties to establish their own agencies to evaluate defendants for release. Another measure would compel bail companies to post the terms of their contracts online and direct the California Department of Insurance — which regulates the bail bond industry — to conduct a review of the surety corporations that back them.

State Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones supports the changes. Citing increases in complaints, he said in a February report that the state should also license bounty hunters, require more data disclosures from bail companies and create special units to investigate bail violations and enforce compliance.

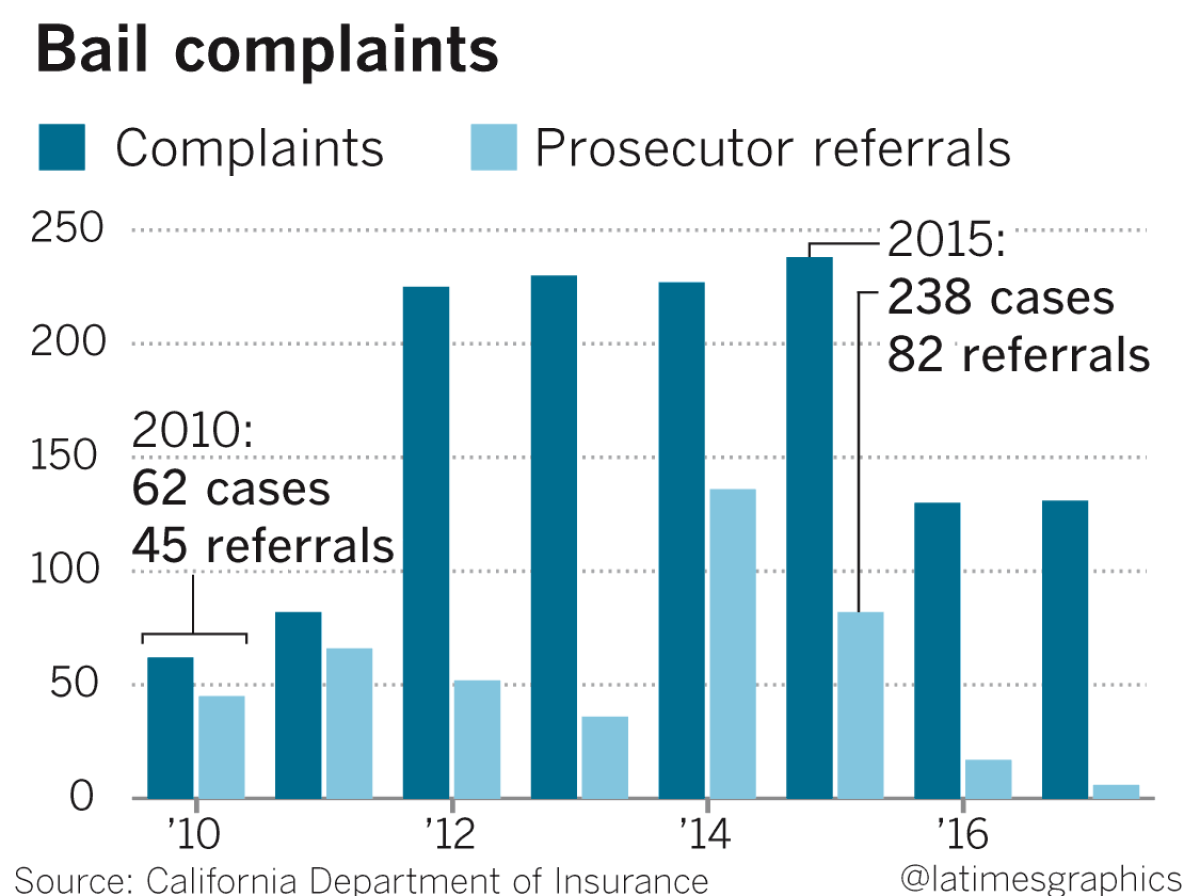

Department of Insurance data show that complaints against agents and companies more than tripled between 2010 and 2012, from 62 to 225 cases. In 2017, the number of complaints was 131, accounting for 10% of all violation allegations sent to the department’s enforcement agency, even though bail makes up less than 2% of the insurance market.

The figures could be even worse. State bail agent associations have told their members to stop filing complaints against other agents and companies while legislative debate is pending, according to a spokeswoman for the Insurance Department. One investigation out of Santa Clara County resulted in the arrests of more than 30 bail agents. They were charged in a scheme to scoop away business from competitors by paying inmates to recruit other inmates for them as clients.

With limited state resources, only a few of the reported cases resulted in enforcement, such as agents having their licenses revoked or facing criminal charges. Legislation to increase funding for investigations and prosecutions was shelved in 2015 and 2016 amid heavy bail industry lobbying.

The state also releases little public information about complaints. Thus, the Bail Reform Coalition, a group of civil rights and criminal justice organizations, on Monday detailed cases against agents and bounty hunters across the state.

The research project is compiled from news stories, court records and regulatory proceedings. It lists agents including Fausto Atilano Jr., who, along with employees, has been charged in Riverside County with pointing guns at residents and, in one case, using a taser weapon against the daughter of a Wildomar mayor. Another offender on the group’s website is former reality television star Arturo Alfred Torres, an agent with bond companies in Los Angeles and Orange counties. He pleaded guilty to felony grand theft in 2016 after investigators said he refused to return $18,000 to the mother of a client whose charges were dropped.

The group cites vocal bail legislation opponents like Teresa Lynn Golt and Lisa Louise Golt. The sisters and founders of Lipstick Bail Bonds have testified at Capitol hearings and passed out chapsticks with their logo, clad in matching pink jackets.

In one 2013 case, the Golt sisters were sued by a man alleging he was injured when they tried to detain him, pepper spraying him and shooting him with a stun gun and rubber bullets. The sisters countered the claims were false, and a judge dismissed the lawsuit. In 2000, they were charged with issuing bail without a license and illegally accessing private information from law enforcement computers. They were sentenced to probation after they pleaded no contest to lesser charges.

Calls and emails to Atilano and the Golt sisters were not returned.

Un, Bender and others in the industry are in favor of increasing standards, improving court evaluations of defendants and lowering bail fees. When it comes to the bigger picture, they remain staunch defenders of bail, saying it is needed to hold people accountable.

Bender contended that counties need trained recovery agents like himself to bring people back to court. Some clients cycle in and out of jail, bailing out with different companies, and he believes court agencies won’t have the resources to help them.

He said his job isn’t like what appears on reality television. He tries talking to his clients about turning their lives around.

“Every once in awhile, I do reach someone,” Bender said. “That is what it’s about for me. Those few people I could reach.”

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.