Must Reads: California homeowners get to pass low property taxes to their kids. It’s proved highly profitable to an elite group

Actors Jeff and Beau Bridges, along with their sister, own a four-bedroom Malibu home with access to a semi-private beach and panoramic views of the Pacific Ocean.

They inherited it from their mother, who had owned the house since the late 1950s when their father, Lloyd Bridges, first made it big in Hollywood.

Earlier this year, they advertised the “stunning Malibu dream” for rent at $15,995 a month — a hefty price tag for a house that has a property tax bill of less than half that.

Like other descendants of a generation of California homeowners, the Bridges siblings enjoy a significant perk that keeps their property tax bill low. Part of that is thanks to Proposition 13, which has strictly limited property tax increases since 1978. But they also benefit from an additional tax break, enacted eight years later, that extended those advantages to inherited property — even inherited property that is used for rental income.

California is the only state to provide this tax break, which was designed to protect families from sharp tax increases on the death of a loved one. Without it, proponents argued at the time it passed, adult children could have faced potentially huge bills, making it financially prohibitive to live in their family homes.

But a Los Angeles Times analysis shows that many of those who inherit property with the tax breaks don’t live in them. Rather, they use the homes as investments while still taking advantage of the generous tax benefits.

In Los Angeles County, as many as 63% of homes inherited under the system were used as second residences or rental properties last year, according to the Times’ analysis. A similar trend was found in a dozen other coastal counties. Prime vacation spots in Sonoma and Santa Cruz have some of the highest concentration of homeowners receiving the benefit.

The inheritance tax break, The Times has found, has allowed hundreds of thousands — including celebrities, politicians, out-of-state professionals and some of California’s most prominent families — to avoid paying the higher taxes owed by newer homeowners. The tax break has deprived school districts, cities and counties of billions of dollars in revenue.

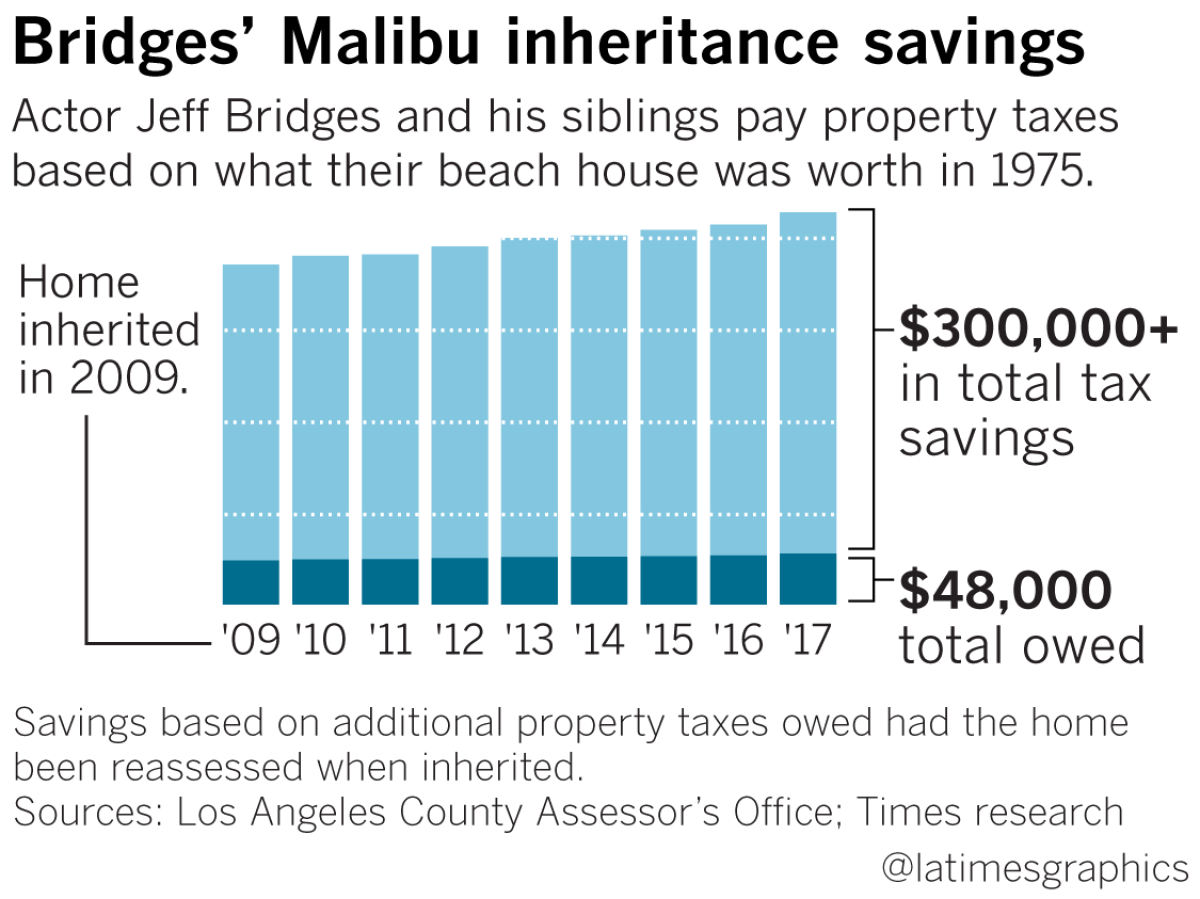

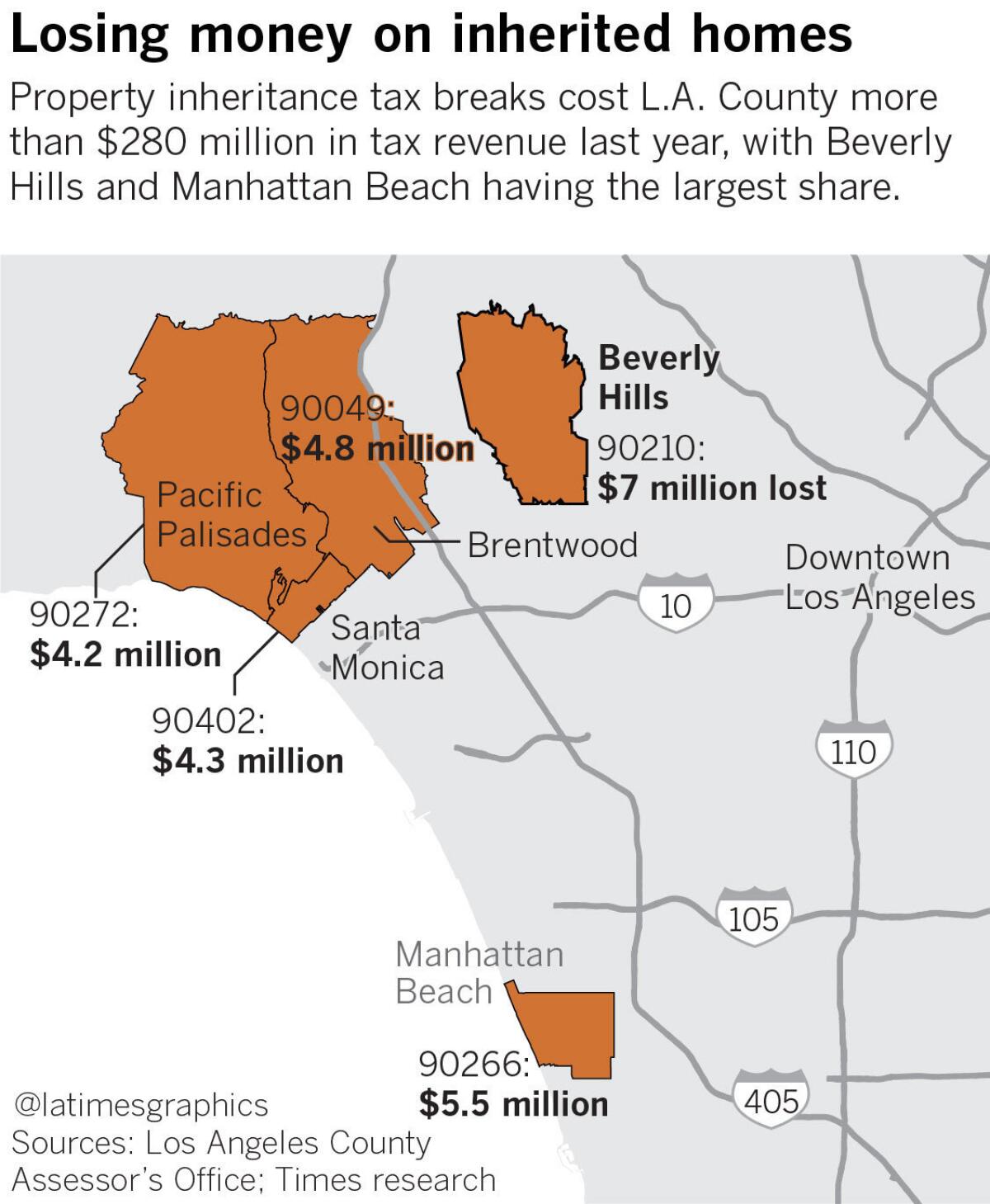

The Bridges siblings, who declined to comment for this article, would have paid an additional $300,000 in property taxes if the house had been reassessed when they inherited it in 2009, according to a Times calculation. In Los Angeles County, the tax benefit cost schools, cities and county government more than $280 million in revenue last year, the analysis shows.

One effect of Proposition 13 and the inheritance tax break has been to create generational inequities between those who have owned homes and those who haven’t. The laws place no limits on how many descendants can take advantage of the benefit, so future generations of Californians whose ancestors purchased houses decades ago will continue to pay property taxes based on values established in the 1970s.

The laws have helped many families stay in their homes without onerous tax burdens. But soaring property values across California also have created windfalls for longtime homeowner families that even the biggest backers of these laws didn’t expect.

Thomas Hannigan, a former state assemblyman from Solano County and author of the inheritance tax break, admits he did not foresee that the heirs of homeowners would use his law as a moneymaker.

“I tried to do the right thing,” said Hannigan, a Democrat, in an interview with The Times. “Obviously, it had unintended consequences.”

Jon Coupal, the head of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers’ Assn., the anti-tax organization founded by the driving force behind Proposition 13, said he believes the inheritance benefit continues to protect children from losing their family homes to tax hikes. But even he was surprised the provision had led to so many heirs using the property as rentals.

“That was probably not in the voters’ minds,” Coupal said.

Less than five miles up the coast from the Bridges house, actor Peter DeLuise inherited a three-story, white-stucco home from his father, comedian Dom DeLuise. Advertisements for the $24,000 monthly rental tout its oceanfront master suite with an attached sauna, walk-in closets and wet bar on the top-floor deck. The rental payment would cover DeLuise’s annual property tax bill in just over three weeks.

The daughter of billionaire arts and education patron Leonore Annenberg would have paid more than $500,000 in additional taxes in the nine years since she inherited a Beverly Hills home if not for the tax break, according to a Times’ analysis. The home is worth an estimated $10.3 million, according to Zillow.

In another case, descendants of a United Airlines founder owe less than $10,000 a year in property taxes for a palatial 1.75-acre estate on the Santa Barbara coast in Montecito that’s on the rental market for $20,000 a month.

In San Francisco’s exclusive Presidio Heights neighborhood, a six-bedroom home with an elevator, a wine cellar, and a painted mural and crystal chandelier on the dining room ceiling is estimated by the real estate website Zillow to be worth nearly $10 million but is taxed based on a value from the 1970s that is just 3% of that figure. The owners, who inherited the property two years ago, recently listed it for $17,500 a month in rent.

To receive the benefit, it isn’t even necessary to live in California. An attorney in Boca Raton, Fla., has advertised the two-bedroom Santa Monica home he inherited from his parents near the Brentwood Country Club for $5,900 a month, which would pay his annual property taxes in a little more than two weeks.

The Times requested interviews with DeLuise and the others. All declined.

To understand the tax break’s effects, The Times obtained a decade’s worth of property records from 13 counties along California’s coast, where the state’s housing problems are the most acute and real estate prices are generally the highest. Those records were compared with public assessor data provided by Zillow.

Up and down the coast, inherited houses are clustered in neighborhoods with higher property values, from the Bay Area’s wealthy Hillsborough area to coastal Santa Barbara. Local governments are missing out on the larger tax payments that would come from these expensive homes. Areas of Beverly Hills and Manhattan Beach could have collected an additional $7 million and $5.5 million, respectively, in property tax receipts last year without the inheritance benefit, The Times found.

Vacation enclaves serve as the most popular locations for heirs using their parents’ homes as investments. Owners of at least five short-term rentals receive the inheritance tax break within five blocks of Beach Drive on the Santa Cruz County coastline alone.

The same trend holds true in affluent pockets of Los Angeles County.

In Malibu, Hollywood Hills and Playa del Rey, more than 80% of owners report their inherited property is not their primary residence, according to The Times’ analysis. Families who have owned property the longest are also more likely to rent the houses out or use them as second residences, the records show. In L.A. County, three-fourths of heirs whose parents owned homes at the time of Proposition 13’s 1978 passage don’t report the property as their primary home, The Times found.

MORE: Inherited properties: How we reported the story »

The tax privileges afforded current homeowner families stand in contrast to the higher taxes many newcomers face. The Bridges children had a $5,700 tax bill last year for their Malibu home now estimated by Zillow to be worth $6.8 million. If someone bought the home at that price today, they’d pay more than $76,000 annually in property taxes.

The higher taxes on properties changing hands has had a major impact, especially on middle- and lower-income Californians trying to enter the market.

California’s home prices have neared record highs, with median values of $539,800 and monthly two-bedroom rents averaging $2,400. The state has the nation’s highest poverty rate when housing costs are included, and 1.7 million families spend more than half their income on rent.

“The story of California in 2018 is skyrocketing inequality,” said Assemblyman David Chiu, a San Francisco Democrat who leads the Assembly’s housing committee. The inheritance tax break, he continued, “has exacerbated that inequality and is symbolic of that inequality. The idea of the American Dream of everyday people being able to make it is completely impacted when the haves get more, and the have-nots have no chance of benefiting from property investment windfalls.”

In the late 1970s, California’s property values were rising and so were the property taxes tied to them. Elderly homeowners became alarmed. Taxes, they worried, would go so high that they couldn’t afford to pay their bills, forcing them to sell their homes. Those fears led to the passage of Proposition 13 in 1978, revolutionizing the state’s property tax system.

The initiative limits property taxes to 1% of a home’s taxable value, which is based on the year the house was purchased. It also restricts how much that taxable value can go up every year even if a home’s market value actually increases much more. After a house is sold, property tax bills are recalculated for the new owner based on the new purchase price. So the longer someone owns their home, the lower their property taxes are as a percentage of the home’s actual market value.

The inheritance tax break, known as Proposition 58, added a new twist. It ensured that the transfer of a home from a parent to a child wasn’t treated like a property sale. Instead, it allows the heirs of the original owner to inherit the lower property tax bill. This is why the Bridges home is still levied property taxes based on its value in the 1970s, instead of its value when the children inherited it in 2009.

The inheritance tax break allows parents to give primary residences to their children, stepchildren, adopted children, or sons- or daughters-in-law without triggering a reassessment no matter how much the home is worth. Parents also can transfer their businesses, farms, second homes and rentals, provided the total assessed value is less than $1 million — something very common for properties owned a long time.

Hannigan said he wrote the inheritance tax break as a way to level the playing field for families, regardless of income. The assemblyman was bothered that under Proposition 13 companies could maintain low property tax bills on their buildings forever even as management — in effect, the company’s owners — changed over time. Families were a sort of corporation, too, and should be treated similarly, he wrote in a June 1985 memo to fellow lawmakers.

“It was the family economic unit that made this country the financial superpower that it is today,” Hannigan wrote in the memo.

The Legislature unanimously supported putting Proposition 58 on the ballot in 1986. It passed with more than 75% of the vote.

The law set California apart. No other state provides similar property tax relief to the children of homeowners, according to the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, a Massachusetts-based think tank that studies land taxation.

At the time, Hannigan said, he and other lawmakers did not consider the long-term effects of Proposition 58. The Legislature, he said, was simply responding to California’s anti-tax political fervor.

“We weren’t practicing good tax policy,” Hannigan said.

U.S. Supreme Court justices have felt the same way.

In 1992, the court heard a challenge to the broad property tax policy created by Proposition 13. Lawyers defending it contended the state was trying to protect elderly homeowners. But during oral arguments, Justice Harry Blackmun questioned why those homeowners’ children received tax breaks, too.

“They get the same benefit and they’re not all that elderly, as I understand it. They’re just sort of a class of nobility in California,” Blackmun said, causing the courtroom to erupt in laughter. “They inherit this tax break and it goes on through generation to generation.”

Still, the court ultimately ruled in favor of Proposition 13. It decided that the state’s unique property tax structure was its prerogative and that it could justify the inheritance tax break on the grounds of supporting neighborhood continuity. But in his dissenting opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens called the inheritance benefit one of the most unfair provisions in California’s system.

The tax break, Stevens wrote, “establishes a privilege of a medieval character: Two families with equal needs and equal resources are treated differently solely because of their different heritage.”

Since then, there has been little public debate over the inheritance tax break. In 1996, voters extended the same benefits to the grandchildren of property owners, a provision rarely used because it requires both parents of the new owner to be deceased. Even so, the inheritance tax break has become pricier than anticipated.

The original estimate of lost tax revenue, adjusted for inflation, was $137 million a year, along with a warning that the price tag would grow every year. Today, the cost has ballooned to more than 10 times that amount, according to a recent statewide report by the state’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office.

The report also determined that about 650,000 property owners in California received the inheritance tax break over the last decade, or one out of every 20 times a property changed hands.

Some who have received the benefit aren’t part of California’s elite and simply see it as a way to ensure property remains in their family.

Bob Flasher’s parents purchased a home along the Russian River in Sonoma County in the early 1970s for less than $30,000.

Five years ago, Flasher, a 73-year-old retired park ranger who lives in Berkeley, inherited the property. He’s replaced the roof, deck and picture windows. To recoup the cost of the improvements, Flasher recently put the property on the rental market for $3,000 a month, which would quickly cover the $2,500 he owes annually in property taxes. Zillow now estimates the home to be worth $744,000.

“If we had had to do a property tax increase, we would have had to sell it,” Flasher said. “People don’t have thousands and thousands of dollars on hand to pay these increases.”

Flasher’s two brothers inherited their parents’ lower property taxes on two other homes, in Berkeley and Sebastopol.

Flasher said he’d be willing to pay more in taxes but argued that the state should instead have higher taxes on corporations. Other defenders of the program contend the state’s taxes already are too high.

And not all of the inheritance tax breaks are going to children renting out their parents’ homes.

Democratic Rep. Brad Sherman lives in a Northridge house his mother transferred to him four years ago after she moved to an independent living facility. It was important to her, Sherman said, to keep the property in the family while she’s alive. She gave the house to him after she discovered she could do so without a tax hit. “This is hardly a tax ruse,” Sherman said.

Others say the inheritance tax break is ripe for reexamination. Children of homeowners are more affluent and have greater financial advantages than those of renters, according to research cited by the legislative analyst. Inherited homes are more likely to have paid-off mortgages and allow children to tap the home’s equity for loans. Plus, white households in California own homes at much higher rates than black and Latino families.

The situation leaves new homeowners at a distinct disadvantage.

James Cunningham, 35, and Heather Mathiesen, 34, had to tap their 401(k) retirement plans to afford the down payment on the $350,000, four-bedroom home they purchased in Lancaster, in the high desert on the outskirts of L.A. County. Cunningham, an engineer, and Mathiesen, a costume designer, had their first child, Hugo, just before they bought the house last fall.

The couple’s first annual property tax bill was $4,800. By contrast, the Bridges family paid $5,700 last year for their home worth nearly 20 times more.

“It’s pretty frustrating to feel like some people are able to follow the rules and get incredible benefits while we’re following the rules and we’re just trying to live,” Cunningham said.

Prospects for changing the inheritance tax break could depend on broader efforts to reexamine the state’s property tax system. The California Assn. of Realtors, a powerful interest group, wants to downsize the program so it could be used just for children who live in their parents’ homes. They would only do so, though, as part of a larger measure that also would expand other Proposition 13 tax breaks.

Chiu, the San Francisco lawmaker, would like to eliminate the inheritance tax break. But he worries that because of its ties to Proposition 13, which nearly two-thirds of likely California voters support, doing so would be politically difficult. Efforts to curtail Proposition 13’s effects over the last four decades have largely failed.

Coupal, the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Assn. president, said the inheritance tax break provides policy benefits. He argued those who want to live in their parents’ homes, maintain family farms or hardware stores or inherit small apartment buildings shouldn’t face huge property tax bills after their parents die.

Still, Coupal said he believes voters did not intend to grant as broad tax relief as they did when they passed the 1986 measure.

“The average voter probably did not have in mind a multimillion-dollar property being given [to children] that they could use as income-producing property and then live out of state,” Coupal said.

But, he added, those early homeowners are simply being rewarded for their smart investment.

“It’s like somebody who invested in Bitcoin,” he said. “Somebody put in $500 in Bitcoin, it’s worth $2 million today. Good for them.”

As for the adult children inheriting old high-value properties and their tax benefits?

Coupal says that’s “the luck of the gene.”

liam.dillon@latimes.com | @dillonliam

ben.poston@latimes.com | @bposton

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.