Capitol Journal: California’s candidates for governor don’t talk about taxes much. They need to start

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — Modernizing California’s archaic, unstable tax system is one of the most important tasks the next governor will face — or should. But it’s not a burning topic on the campaign trail.

That’s because Democrats feel it’s an issue that can only cause grief.

Republicans like to rail against high taxes and call for them to be lowered. But they no longer seem capable of winning the state’s highest office.

The biggest problem with California taxes is that they were designed for a retail economy that no longer dominates. We’ve become a service economy that basically isn’t taxed.

To make up for it, state income taxes have been raised to the sky, particularly on the rich. California’s top rate is 13.3%, astronomical for a state. And that tax revenue is volatile and unreliable because it’s tied largely to capital gains. Those capital gains dwindle during a recession.

When the economy dips, income taxes overall fall into the dumpster, forcing sharp cuts in funding for education, healthcare and other government programs.

Most Californians — especially Republicans — naturally believe they’re overtaxed. A recent poll by the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California found that 56% of adults think they pay more state and local taxes than are warranted.

California’s taxes generally are high, no question. But the overall state tax burden relative to personal income hasn’t changed much in the last half-century. In 1968, total state taxes per $100 of income were $6.36. This year, they’re projected to be $6.94. The figures have consistently hovered around those marks.

The state Franchise Tax Board released data last week that illustrated the state’s unhealthy reliance on the rich. In 2016, the top 1% paid 45.8% of the state income tax revenue while accounting for 23.1% of the personal income. The top 10% paid 78% of the total tax revenues. The bottom 80% contributed just 10.6%.

To be in the top 1%, you’d have to earn at least $580,429. The threshold for the top 10% was $157,451.

What California needs to do is lower income tax rates to a more reasonable ceiling, say 10%. Additionally, the state should reduce the sales tax rate while broadening the levy to services. Clamp a sales tax on services provided, for example, by lawyers, accountants and architects. They’re used mostly by the wealthy anyway. The state should also tax auto repair labor and entertainment, such as Dodgers tickets.

In addition, there’s the seemingly sacrosanct Proposition 13 property tax law, which will be 40 years old in June. It needs retooling.

Because of the law, taxes are assessed less on a house’s worth than on how long the owner has lived in it. How silly is that? Taxes on similar houses next door to each other can vary by thousands of dollars. If you want to help retired senior citizens keep their homes, just freeze their property taxes.

A more addressable problem involves large commercial property. It’s reassessed only when more than half of the ownership turns over at once. A proposed November ballot initiative would assess business property at market value.

Proposition 13 substantially lowered property tax revenue for schools and local governments, which turned to the state for bailouts. State government took over most of the financing for schools and raised income and sales taxes to pay for it. The state universities then got less and tuitions leaped dramatically.

It’s all a mess.

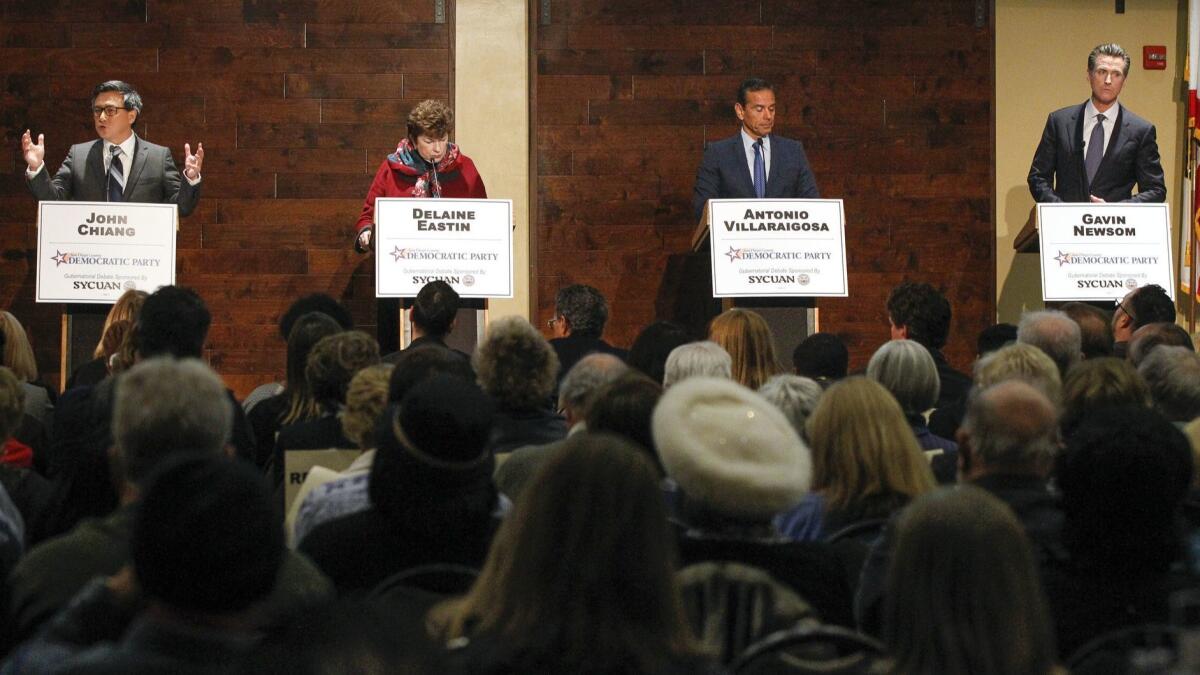

Democratic gubernatorial candidates agree, but shy away from offering detailed proposals. It’s a risky subject that provides killer scripts for attack ads.

All the candidates promise to address the issue if elected. Gov. Jerry Brown hasn’t. He made the volatility worse by winning voter approval of a soak-the-rich income tax hike to balance the budget.

Brown, however, did create a modest “rainy-day” fund to stash surplus capital gains revenue in good times to be spent when the economy inevitably turns sour. He’s proposing to fill the fund at its $13.5-billion legal capacity in the next fiscal year.

Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, the front-runner to replace Brown, says he’s game for a significant tax code update.

“We can broaden the [sales] tax base,” Newsom has said. “We can actually tax the economy that exists today, not the economy of 100 years ago, which is our current tax structure.”

Newsom and all the Democratic candidates say they’re willing to rethink Proposition 13.

“Proposition 13 and the entire tax system is broken and needs to be reexamined,” said former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa. “That means we need to look at every aspect of our tax system comprehensively.”

Villaraigosa says he won’t support a proposal to change one tax only. He wants a thorough “restructuring” that makes the system “more stable, fair and better able to promote the creation of high-wage jobs.”

State Treasurer John Chiang pledges “to lead a major overhaul of our tax system in my first term as governor.” California “hasn’t overhauled its tax system since 1935,” he adds. “It’s still stuck in the agrarian economy.”

Former state schools chief Delaine Eastin wants to tax commercial property at market value and use most of the revenue for education. “California got rich because it invested in education,” she says. “Then we got amnesia and forgot how we got here.”

There are other important issues the next governor should face: regulatory red tape, homelessness and water.

But none are as politically dicey as taxes. That’s why we don’t hear much about it. We should.

Coverage of California politics »

Follow @LATimesSkelton on Twitter

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.