It could be another ‘Year of the Woman’ in California, but probably not

Comedian-turned-activist Chelsea Handler made a prediction a few months ago.

“They had the ‘Year of the Woman’ in 1992,” Handler told a crowd, almost all women, who had gathered in a Los Angeles hotel ballroom over avocado toast and roasted tomatoes at a brunch for Emily's List, the group dedicated to electing pro-choice Democratic women.

"This is obviously going to be a bigger year for women.… Hopefully we'll win so much we'll be so sick and tired of winning."

In California, that’s a wish that is likely to remain unfulfilled, with many top-tier female candidates at risk of getting left behind in the approaching primaries.

Ranking the toughest House races in California »

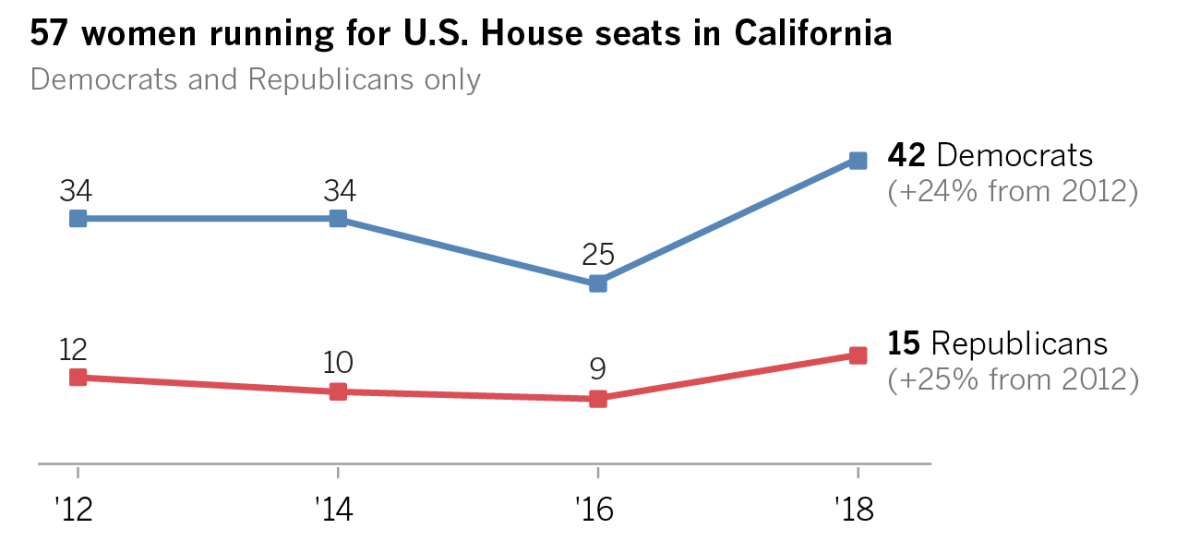

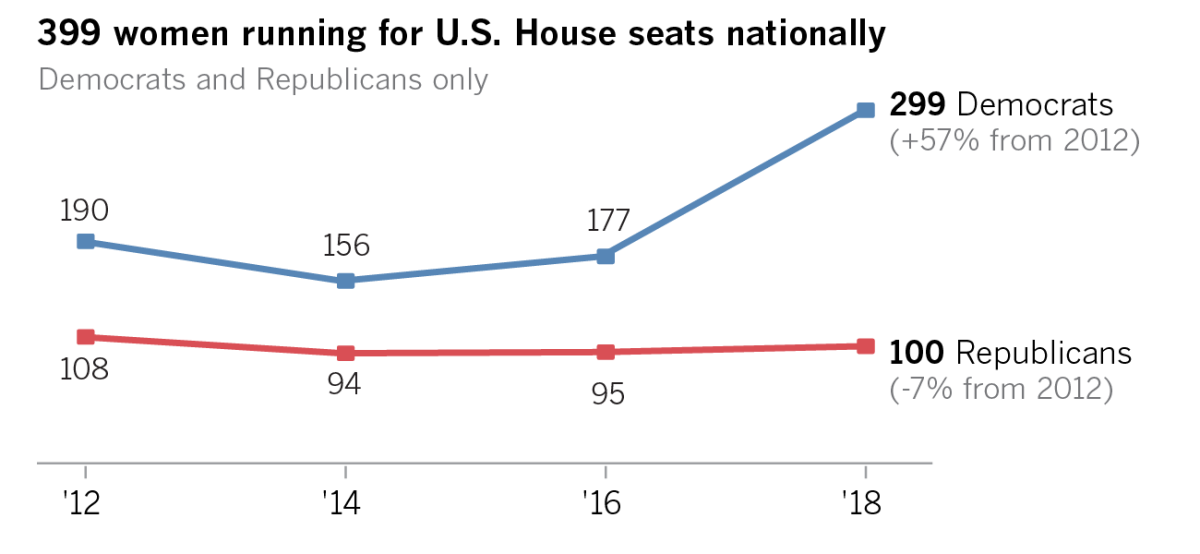

It's not for lack of candidates. On June 5, a record 57 women from the two major parties — mostly Democrats — will be on the ballot for House races in California, a 24% increase from the last record in 2012. Nationwide, it’s about 400, another record. Many are established professionals — doctors, nurses, lawyers, technology executives and nonprofit directors — who are running to oppose President Trump. It’s easy to understand why Handler and so many others are feeling bullish. Results in early primary states have shown enthusiasm for women candidates, including, in Georgia, the first black woman to receive a major party nomination for governor of any state.

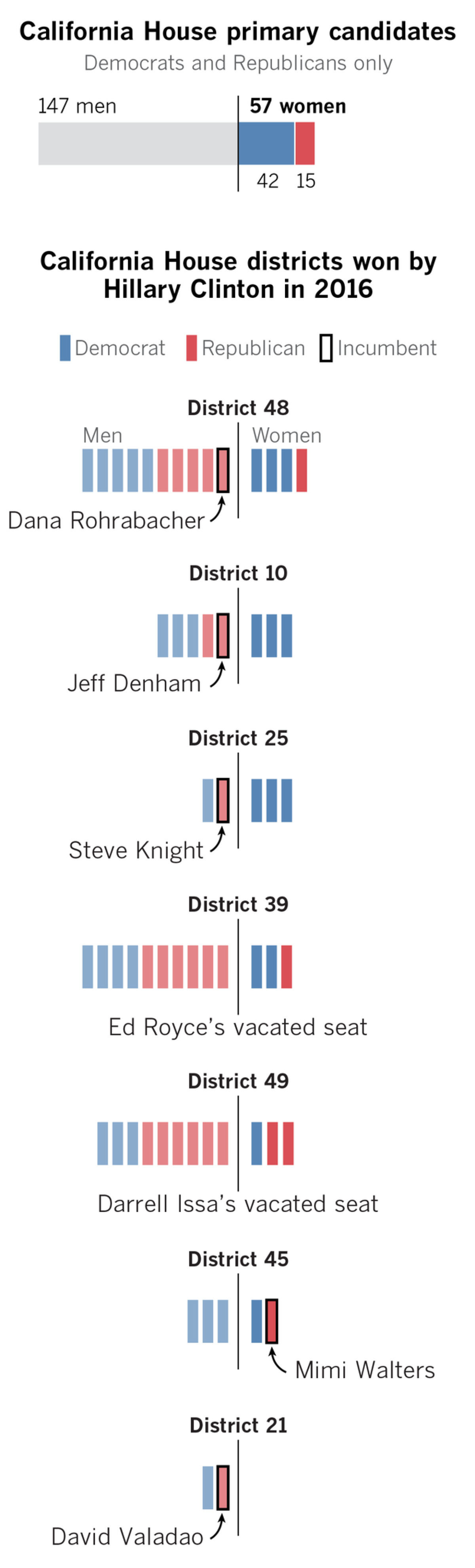

But in California, crowded primaries in crucial battleground districts, entrenched incumbents, notoriously expensive media markets and a top-two primary system that may prove disastrous for Democrats are some of the formidable barriers women face.

"I think that female candidates in California are having a really hard time," said Mai Khanh Tran, an Emily's List-backed pediatrician running in the 39th Congressional District to replace retiring Rep. Ed Royce of Fullerton. "The truth is that on the ground, women candidates are not getting the support and the help that we need to become really competitive."

Tran, 52, who came to the U.S. as a refugee from Vietnam, is one of six Democrats running in the district, where her party could be shut out of the November runoff due to the state's primary system, which advances the top two vote-getters regardless of party.

Despite Tran’s relatively strong fundraising, the race on the Democratic side appears to have mostly come down to health insurance executive Andy Thorburn and Navy veteran Gil Cisneros. Both are millionaires who have vast resources to get their message out.

The term 'Year of the Woman' doesn't have any teeth if it doesn't lead to any of the outcomes that we're seeking.

— Democrat Rachel Payne, who is running in the 48th Congressional District

A similar scenario is playing out in the 48th Congressional District, where Democrat Rachel Payne is one of four women on the ballot against GOP Rep. Dana Rohrabacher. The primary fight on the left there seems to be an expensive battle between two men: stem cell researcher Hans Keirstead and real estate investor Harley Rouda.

"The term 'Year of the Woman' doesn't have any teeth if it doesn't lead to any of the outcomes that we're seeking," said Payne, a former Google executive who’s now chief executive of a media research firm.

Like many of this year’s women candidates, Payne launched a campaign against the toughest type of candidate to beat: one who’s already in office. Rohrabacher, a 15-term incumbent in a historically safe Republican seat, is vulnerable this year because of eroding support within his party and intense scrutiny of his pro-Russia sentiments, but he has the backing of the GOP establishment. Congressional incumbents are generally reelected 90% of the time.

Debbie Walsh, director for the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, finds herself pointing that out so often lately that she refers to herself as "Debbie Downer."

She and her colleagues warn that despite the flood of women candidates and an apparent bump in support for them in some early primary states, talk of a "pink tsunami" to counteract Trump may be overblown.

Nationwide, six major party women candidates are running against incumbents. In California, that figure is 60% and just six major party candidates are running for the state’s two open seats. And even though women are breaking records this year in raw numbers, men still make up roughly three quarters of major party House candidates in California and nationally.

The top-two primary system has put the focus on getting a Democrat, rather than a woman, into the top two.

None of the women running in the seven GOP-held House districts carried by Hillary Clinton in 2016, considered key to Democrats’ chances of retaking the House, managed to get the state Democratic Party nod at its February convention.

It was a moment, said Payne and Tran, that crystallized their frustration with the process. “Do they mean it? Do they want to see women in Congress?” Payne said. "Or is it, 'Let's talk about empowering women and not do anything about it.’"

Afterward, Tran said she reached out to Emily’s List for more assistance for its candidates here. While the group’s independent expenditure arm has spent a couple million dollars to bolster four of its endorsed candidates in California, none has been directed to Tran’s race. (The vast majority of the money has gone to support 49th District candidate Sara Jacobs, whose grandfather Irwin Jacobs, cofounder of Qualcomm, contributed more than $1 million to the group.)

Tran said she was taken aback when Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee staffers and several members of California’s House delegation tried to dissuade her from running, showing her internal polls that put her behind her male counterparts. One mentioned she risked becoming “a spoiler,” Tran said.

Even candidates who have held office, including former Riverbank mayor Virginia Madueño in the Central Valley, or those with seemingly unlimited money, such as Jacobs, have struggled against men who ran as challengers in the last cycle and can benefit from the millions of dollars spent to boost them two years ago.

Some have been told by activists or local leaders that they should step aside. “I was the one told over and over again, ‘Why are you going straight to Congress? Why aren’t you waiting your turn?’” said Katie Hill, former executive director of a homelessness nonprofit who is facing the Antelope Valley’s GOP incumbent, Steve Knight, and attorney Bryan Caforio, a fellow Democrat and two-time challenger. Hill has out-raised them both for the last seven months and of the Emily’s List endorsed candidates is considered to have one of the best shots of making it past June 5.

But even if she does, she’ll have to overcome historical odds: In 2012, the last record year for women candidates in California, 29 non-incumbent women ran for the House. Just six made it out of their primaries and two of them became congresswomen.

The strategic labyrinth of California’s top-two primary, passed by voters in 2010, provides a stark contrast to 1992, the original “Year of the Woman,” when the mission was much simpler. After Anita Hill’s testimony to an all-white, all-male panel alleging sexual harassment when she worked with Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, women were elected to the House and Senate in record numbers, tripling the number of female senators to six.

Rose Kapolczynski, who managed Sen. Barbara Boxer’s 1992 campaign and remained her political consultant until she retired last year, recalls how women would walk into Boxer’s campaign office, hand her $5 or $10 for the campaign or ask to volunteer.

“There was a direct relationship between seeing those hearings … and then taking action to elect a woman,” Kapolczynski said. “Now, it’s much more diffuse. There is a Trump outrage every day on a wide variety of issues.”

In a state dominated by Democrats, it’s actually Republican women with experience winning elections who are best positioned to get through California’s primary and the November runoff.

An incumbent like Rep. Mimi Walters of Irvine, the only Republican woman in California’s delegation, could benefit from California voter assumptions that Republican women candidates in the state are more moderate, says Democratic pollster Celinda Lake. So could former GOP Assemblywoman Young Kim, running to replace Royce, and Diane Harkey, the state tax board chair looking to replace Rep. Darrell Issa. The two have led internal polls from both parties.

“Coming in just out of the gate, it is difficult for anyone, male or female,” Harkey said. “You either have a constituency or you don’t. And if you don’t, you shouldn’t be running for office.”

Lucinda Guinn, vice president of campaigns for Emily’s List, said its candidates are used to being underdogs and called California’s primary system an “added complication.” She acknowledged that progress for Democratic women in the state may be incremental.

“But our success is not defined by one election night,” she added. “If that means our candidates run and get really close, they’re probably the front-runner for the next time.”

Boxer, who started a super PAC to help flip House seats, agreed with Guinn’s long view.

“People say ‘Year of the Woman’ again — I don’t care,” Boxer said. “It’s been a steady, slow climb and the most important thing to me is that it continues to be a steady climb.”

Payne won’t continue that climb this year. Though her name will remain on the ballot, she announced at the end of April that she would stop campaigning against Rohrabacher, citing concerns over Democrats splitting the vote.

“Ultimately, it’s our country that’s at stake,” she told an audience at the end of a debate. There were tears in her eyes and she was in the white pantsuit she wore in 2016 to vote for Clinton for president, a nod to the suffragettes of the early 1900s.

“It represents strength, it represents the power of commitment to the cause,” Payne said afterward.

Payne hasn’t said whether she will run again for the House in her Orange County district. But she hasn’t ruled it out.

More stories on California politics »

For more on California politics, follow @cmaiduc.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.