Here’s how construction worker pay is dominating California’s housing debate

- Share via

The union representing construction workers, State Building & Construction Trades Council of California, also known as the Building Trades, is the most powerful group influencing the Legislature’s response to the housing crisis. It has worked to make sure union-level pay, known as “prevailing wage,” is a consideration in any major housing bills.

Here’s how prevailing wage works, how labor’s been so influential and why prevailing wage is so important in the housing debate.

What’s a prevailing wage?

The definition of prevailing wage is simple, but that’s where the simplicity of the issue ends.

The prevailing wage is the predominant wage for construction work in a region. For example, the most common wage earned by plumbers in the Bay Area is the prevailing wage for plumbers there. The same method applies to carpenters, roofers and all 25 other construction worker jobs across the state.

Because labor contracts with developers pay every construction trade the same rate, the most common construction worker wage is most often the union wage. Twice a year, the state surveys developers to determine what the rates should be.

And because prevailing wage laws like the one in California require contractors to pay such wages even without union contracts, the issue is highly political.

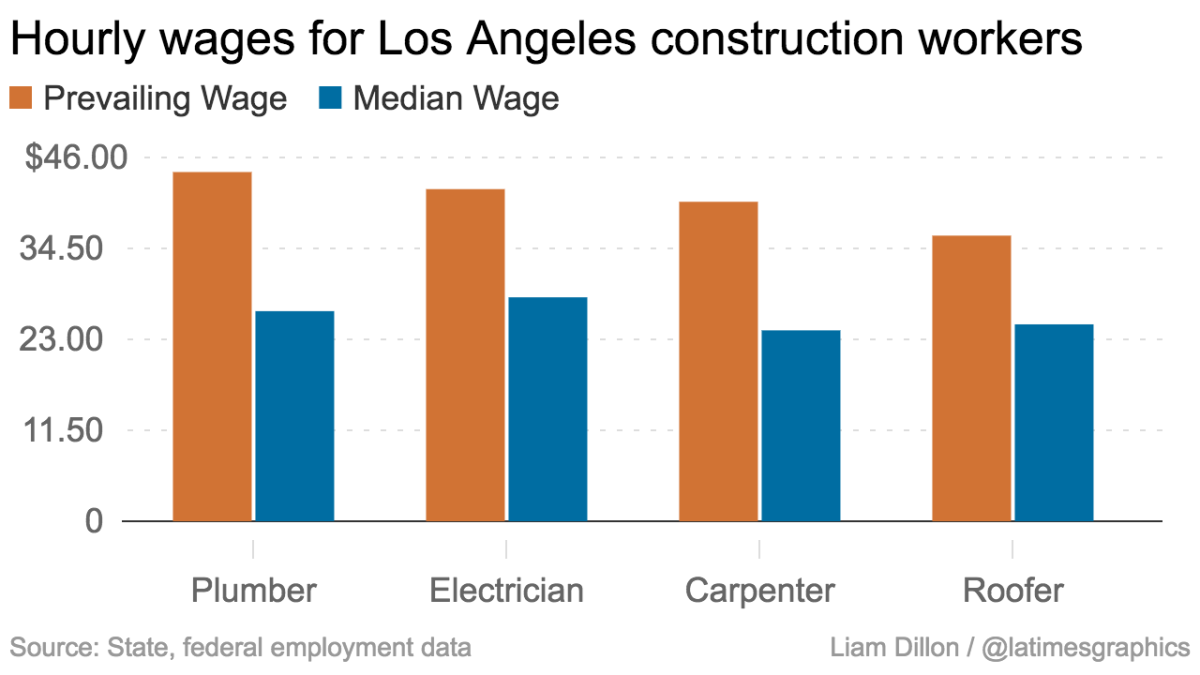

Construction workers who make prevailing wage earn a lot more than those who don’t

Here’s a breakdown of how much some construction workers earn per hour if they get the prevailing wage in Los Angeles compared with the median pay for those same jobs:

Those numbers don’t fully capture how much more construction workers who earn prevailing wage make compared to those that don’t.

Take retirement, health insurance and other fringe benefits, for instance. Unionized construction workers — whose pay often is the standard for prevailing wage — receive roughly double the benefits of nonunion workers, according to unpublished national estimates from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

California has broad prevailing wage laws on housing — and they’re probably not going anywhere

California mandates developers to pay prevailing wage on most taxpayer-subsidized low-income housing projects, rules that go beyond what other states require.

These mandates have increased developers’ costs and, as a consequence, reduced the number of homes they’ve been able to build — especially for low-income residents, said Rob Wiener, executive director of the California Coalition for Rural Housing.

“We have the worst affordable housing crisis we’ve ever had in the state,” Wiener said. “We should be trying to find ways to reduce the cost of building housing — especially for those who the market will never, ever be able to help.”

But prevailing wage advocates, chiefly the Building Trades, have made an argument that has resonated with lawmakers: No one who builds affordable housing should earn so little that they need affordable housing themselves.

Sen. Toni Atkins (D-San Diego), who has worked in low-income housing and whose wife is a low-income housing consultant, said that mandating prevailing wage on public housing projects is a settled issue at the Capitol.

“I’m an affordable housing advocate and I have been for two decades,” Atkins said. “When my friends in the housing community say, ‘Can we talk about prevailing wage?’ I say no.”

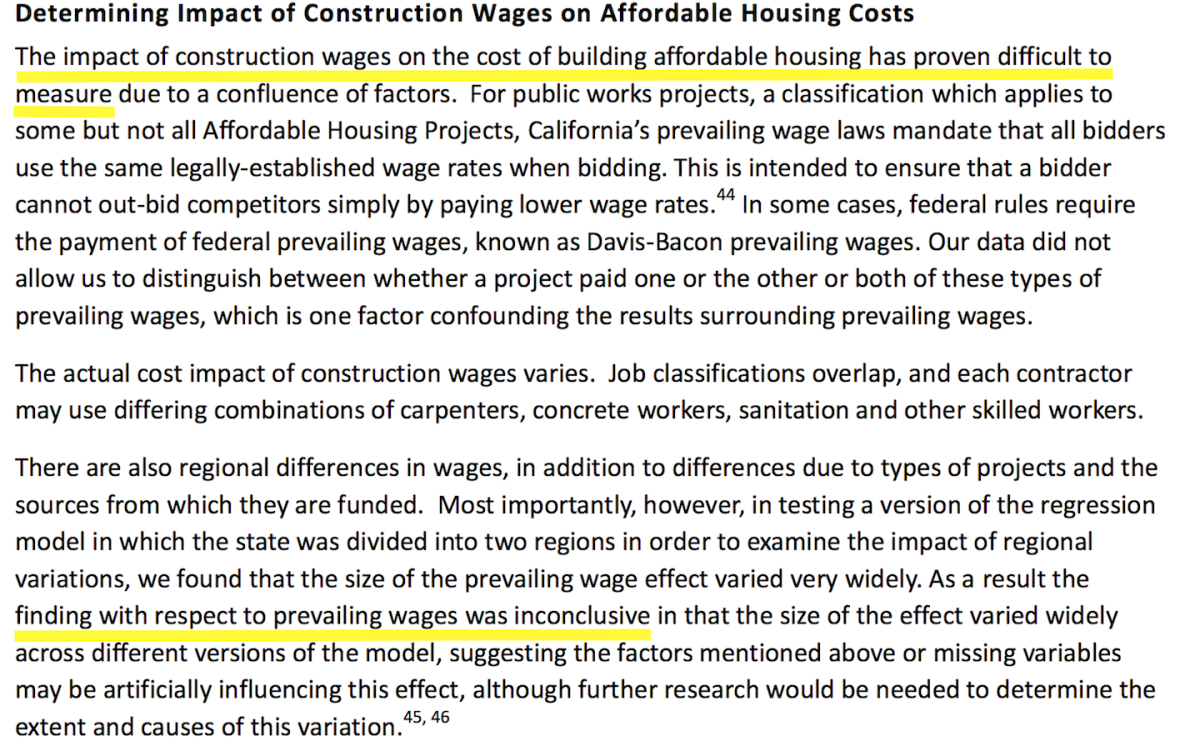

No one knows how much prevailing wage increases the costs of homebuilding — but unions and developers are interested in the answer

It’s hard to determine how much more paying prevailing wages adds to the cost of building homes. Consider the difficulty in finding two housing projects with different wage scales, but built at the exact same time and in the same place, at the same size and with the same materials. That’s the challenge facing any researcher attempting to gauge the impact of prevailing wage.

Here are some estimates on how prevailing wage affects California residential construction costs:

| Author | Percent Cost Increase |

|---|---|

| UC Berkeley | 9% to 37% |

| The California Institute for County Government | 11% |

| National Center for Sustainable Transportation | 15% |

| San Diego Housing Commission | 9% |

| Smart Cities Prevail | 0%* |

| Beacon Economics | 46% |

*No cost impact, especially when taking into account increased worker productivity and savings from decreased public subsidies

Labor economists take issue with the higher-end estimates. They believe those figures inflate how much worker pay makes up in total construction costs, which also include materials and land. Scott Littlehale, a senior research analyst with the Northern California Carpenters Regional Council labor group, has examined state low-income housing data and found that prevailing wage had no statistically significant impact on construction costs.

“I have no evidence it’s a double-digit number,” Littlehale said.

Last year, Los Angeles developers and business groups opposed to a ballot measure that expanded prevailing wage mandates in the city hired economist Christopher Thornberg to estimate the increase in construction costs.

Thornberg said in an interview his conclusion that costs would rise by 46% was ultimately too high. But he still believed the impact of prevailing wage was substantial, given the vast differences in pay.

“You cannot have that kind of pay increase and not think it’s going to affect bottom line costs,” Thornberg said.

Labor influenced a state study of housing costs

Gov. Jerry Brown has long railed against the high cost of constructing low-income housing in California, a price tag that now averages $332,000 per unit.

State housing officials set about figuring out why, and in 2014 released a 73-page study. The effect of prevailing wage, the report said, couldn’t be determined:

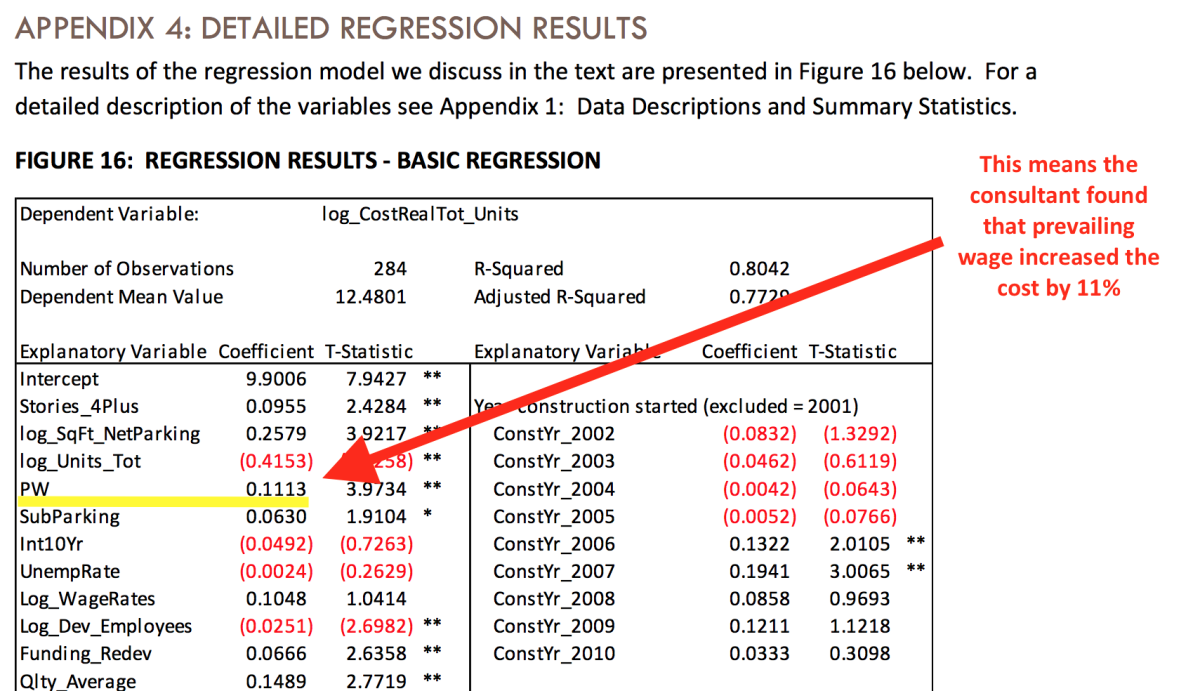

But Matthew Newman, the consultant the state hired for the study, had reached a conclusion.

“We found that projects that were built with prevailing wages were more expensive than those that weren’t,” Newman said.

In the report’s appendix was Newman’s finding that projects that paid prevailing wage were 11% more expensive to build — excluding the cost of land:

Claudia Cappio, who served in several housing roles in the Brown administration, said one reason the number didn’t appear in the report’s main section was that labor unions fought it.

“I wouldn’t call it pushback,” Cappio said of labor’s rejection of the number. “I’d call it lively discussion.”

Labor economists ultimately were able to convince the state of enough uncertainties in the prevailing wage analysis — notably discrepancies between Northern and Southern California data — that the study shouldn’t reach a firm conclusion on the issue, Cappio said.

Robbie Hunter, the head of Building Trades, makes no apologies for the union’s involvement. Some prevailing wage reports, Hunter joked, go so far as to “blame us for global warming.”

“All of a sudden when we start expressing our opinion with the facts that we have, people seem to think that we don't have the right to do that,” Hunter said.

A labor union holds a grudge against a UC Berkeley professor

Last spring, Brown introduced a plan that would have eliminated some local housing regulations for developers if they agreed to set aside a portion of their projects for low-income residents.

The Building Trades opposed the measure. They didn’t like that the proposal — known as “by right” because it would have given developers the “right” to build — didn’t require qualifying projects to pay prevailing wage to construction workers.

Ben Metcalf, Brown’s top housing official, told the Times last year that prevailing wage wasn’t included because the program was voluntary: Higher pay for construction workers would make it too costly for developers to opt in.

The construction workers union started a Facebook group called Californians Against Profiteering and bought online advertisements to oppose the plan.

The group went after Metcalf, calling him “the fox guarding the henhouse.”

They went further. Posts also targeted UC Berkeley professor Carol Galante, who is one of the state’s foremost affordable housing experts, and Bridge Housing, one of the country’s largest nonprofit housing developers. Here’s a post against Galante:

Before Galante came to Berkeley, she was Bridge Housing’s CEO and a top official in the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development under President Obama. Metcalf worked for her in both places.

Labor leaders believe Galante undermined prevailing wage while she was in the Obama administration. They argue, among other things, that under the guise of the mortgage crisis, she waived rules requiring developers to pay the wages on projects funded by federal housing loans.

“Why would we target her? We targeted her because of her history,” Hunter said. “When someone steps up and they say, ‘I've spent my life in affordable housing’ and they use that as a shield to destroy workers' wages, we think the whole story needs to be told.”

Galante said she was baffled when she saw labor going after her. She said she’s never targeted unions, though she did move to exempt prevailing wage from a small federal low-income tax credit program in hopes that more developers would subscribe.

Told Hunter’s comments, Galante said: “It’s offensive that my entire career in helping to create affordable housing would be smeared in that way.”

The governor’s housing plan failed, but labor’s questions about Metcalf and Galante didn’t stop.

In January, Metcalf sat in front of a state Senate committee for his official confirmation hearing. His first questioner was Sen. Connie Leyva (D-Chino). Leyva spoke with Cesar Diaz, the Building Trades’ political director, before the hearing.

“She wanted to do her homework,” Diaz said. “We provided information for what we know about Ben Metcalf and our experience with him.”

At the hearing, Leyva asked Metcalf what he thought about prevailing wage and referenced a policy that temporarily waived prevailing wages on projects financed by federal housing loans — the policy behind the Building Trades’ criticism of Metcalf and Galante.

Metcalf replied that he supported prevailing wage just as the governor did. After some back and forth, Metcalf ultimately said that the prevailing wage should be paid “where appropriate.”

Leyva smiled as she ended the conversation: “From my perspective, prevailing wage is always appropriate, wherever it may be.”

Construction worker pay is at the center of the Capitol’s housing debate

The governor’s housing plan failed last year in large part because of the Building Trades’ opposition.

Lawmakers have taken labor’s message to heart.

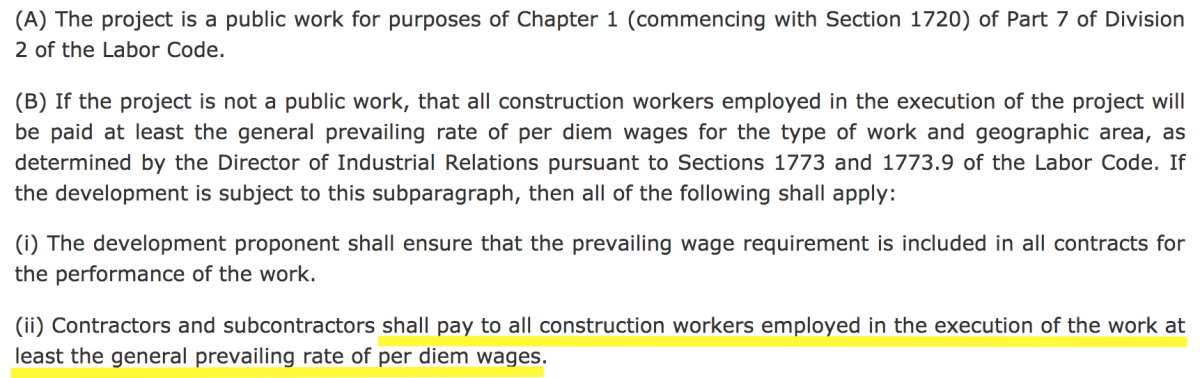

This year, multiple legislators have introduced more limited versions of Brown’s proposal. Prevailing wage is in them.

Here’s Senate Bill 35 from Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco):

Assembly Bill 1585 from Assemblyman Richard Bloom (D-Santa Monica):

And Assembly Bill 73 from Assemblyman David Chiu (D-San Francisco):

Wiener, who was elected in November, called Diaz, the Building Trades’ political director, before he took office to ask him what labor unions wanted in the housing bill he planned to introduce.

“My first phone call was to Mr. Diaz to say, ‘We’re doing this. We want to work with you,’” Wiener said at a recent committee hearing.

But despite the prevailing wage mandates, the construction workers’ union isn’t on board.

Right now, prevailing wage only applies to housing projects that receive public dollars. If any of these bills pass, it would expand prevailing wage to apply to the private projects that qualify for faster local review. But Hunter argues that the bills would prevent labor unions from negotiating for worker pay and other labor standards on a project-by-project basis through existing public and environmental reviews.

Developer greed, Hunter said, is the primary reason for the state’s housing shortage — not higher wages for construction workers.

“Housing developers are like the Saudis: They control the oil price,” Hunter said. “When their profit isn’t what they want, they turn the valve and they reduce the building.”

Labor opposition has hovered over much of the housing debate at the Capitol this year. Wiener’s bill squeaked through a committee last month with the Building Trades opposed. Bloom dropped his bill after the Building Trades came out against it.

Twitter: @dillonliam

ALSO

Governor is pessimistic on major deal to address California's housing affordability crisis

Why construction unions are fighting Gov. Jerry Brown’s plan for more housing

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.