Capitol Journal: Brown was obsessed with twin-tunnel vision. Newsom has a more realistic view

Reporting from Sacramento — A potential grand compromise to settle a decades-long water fight has been obvious for years but blown off. Now Gov. Gavin Newsom is forcing all combatants to consider it seriously.

California’s water future hinges on the ultimate deal.

The battle has been over whether to bore two monster water tunnels under the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta or to build none at all. The solution: Duh. One tunnel.

Newsom decreed one tunnel as the likely sweet spot for a deal last week in delivering his first State of the State address.

It’s an answer neither side particularly likes but seems resigned to reluctantly accept.

“Sometimes when you come up with an idea that nobody likes it’s a fair compromise, and sometimes it just means it’s a bad idea,” says Jeffrey Kightlinger, general manager of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

The MWD is the twin-tunnel project’s principal backer — aside from former Gov. Jerry Brown — and it’s biggest bankroller.

“I can’t imagine us walking away from one tunnel just because it doesn’t work as well as two tunnels,” Kightlinger says.

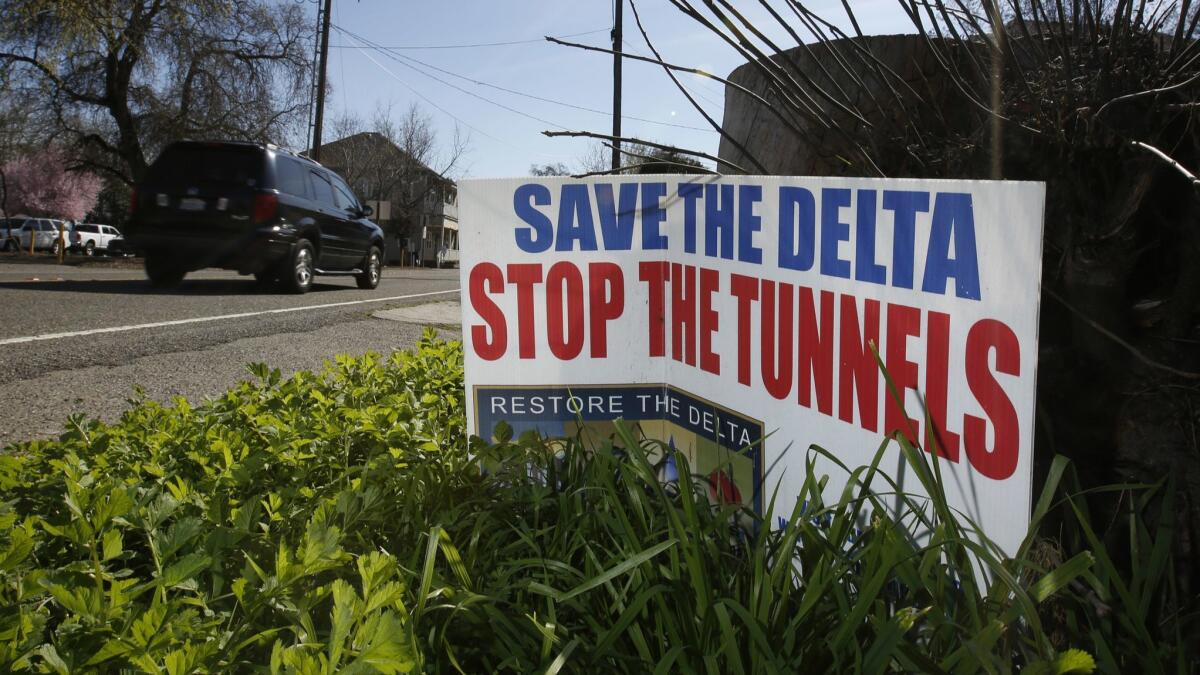

On the other side is a coalition of delta farmers, local communities, environmentalists and northerners who fear a “water grab” by big cities, especially in Southern California, and by San Joaquin Valley corporate farmers.

“We’re delta people and we don’t like tunnels,” says Barbara Barrigan-Parrilla, executive director of Restore the Delta. “Our plan is a ‘no tunnel’ plan.

“But I swore under oath at a state water board hearing that we would evaluate any new project with fresh eyes. One tunnel can still cause a tremendous amount of damage. But we have to see what type is proposed and what the design is.”

Later, in a statement that was striking for conciliation — a rarity in today’s polarized politics — Barrigan-Parrilla urged tunnel opponents to cool it before they start attacking Newsom’s peace offering.

“Let’s breathe and be grateful,” she said. “After more than 12 years of daily combat with two prior governors, Gov. Newsom heard us. That is huge…. We matter…. This is a major shift in the water narrative of California.

“Expecting a California governor, who must represent the interests of all its people, to pick one side only in California’s ongoing water battles is simply unrealistic.… He is not going to alienate a sizable and powerful water industry.

“Dance, sing, have a few drinks and celebrate.”

Coverage of California politics »

That style of candor and pragmatism has become an endangered species in Sacramento and Washington, although Newsom seems to be trying to salvage some semblance of it.

In his State of the State address, the new governor might have been a tad naïve when he declared: “We have to get past the old binaries, like farmers versus environmentalists, or North versus South.”

Good luck trying to coax valley farmers and coastal fishing interests into singing “Kumbaya.” The more delta water is delivered to crops, the less there is for struggling salmon.

Newsom used his speech to pare back both of Brown’s signature legacy projects: the $77-billion bullet train and $17-billion twin tunnels. He could have let both linger for a while but decided to clear the air soon after taking office.

He asserted “there simply isn’t a path” financially to lay tracks from Los Angeles to San Francisco, as planned, and announced he’ll focus on completing a high-speed rail line between Merced and Bakersfield. He objected to calling it a “train to nowhere.”

On the delta, he said: “I do not support the Water Fix” — Brown’s name for the project — “as currently configured. Meaning, I do not support the twin tunnels…. I do support a single tunnel. The status quo is not an option.

“Our approach can’t be ‘either/or.’ It must be ‘yes/and.’ Conveyance and efficiency. And recycling projects like we’re seeing in Southern California’s [MWD], expanding floodplains in the Central Valley, groundwater recharge like farmers are doing in Fresno County. We need a portfolio approach to building water infrastructure.”

The price tag for a single tunnel is estimated at $11 billion, paid for by water users.

At the heart of the water fight has been whether the delta should be treated as a unique wildlife estuary, recreational haven and small farming community, or a plumbing fixture. A 2009 law says it should be managed as both. But that seems an impossible needle to thread. And power politics has always favored the plumbing fixture.

The delta supplies water for 25 million people and 3 million acres of cropland. Giant pumps at the delta’s southern end feed aqueducts, reversing river flow and confusing small salmon headed to the ocean. The fish often get gobbled up by lurking predators or the pumps. So the pumps sometimes are shut down, angering farmers.

Brown’s solution was to dig two 35-mile, 40-foot-wide tunnels from the delta’s north end, carrying fresh Sacramento River water under the estuary directly to the aqueducts. Don’t run the pumps so much.

Opponents complained this would rob the interior delta of fresh water needed for people, crops and fish — not to mention the chaotic mucky mess created by a decade of tunnel burrowing in this bucolic backwater.

But one tunnel might be more tolerable. Would one work?

Better than none, say valley and southern water interests.

It depends on the tunnel size and how it’s operated, both sides say.

Brown was obsessed with twin-tunnel vision. Newsom has a more realistic view.

Twitter: @LATimesSkelton

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.