Essential Politics: Voters expect Biden to hit gridlock but differ over chance of compromise

- Share via

WASHINGTON — President Biden’s exhortations about unity and bipartisanship haven’t suddenly bridged America’s yawning partisan divide — one week into office, that would be a bit much to expect — but measured by public opinion so far, he has gotten off to a reasonably good start, with a path toward potential expanded support.

Comparison with his predecessor, both in their starting points and in their initial steps, provides some instructive contrasts.

President Trump started the way he finished — a chief executive with support from a minority of Americans. His first big act in office cemented that position. Four years ago this week, Trump issued his Muslim ban — a bar against travelers entering the U.S. from seven Muslim-majority countries. The executive order caused chaos at airports and signaled the ascendance of “my two Steves,” as Trump sometimes called them: his political strategist Stephen K. Bannon and policy advisor Stephen Miller.

Bannon, of course, did not last a year in his White House post, but the strategy he laid out, starting with the travel ban, set the pattern for the entire Trump presidency: Play to the base. Trump relentlessly sought to reward the loyalty of those who already belonged to his camp at the cost of inflaming those who disagreed with him.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Four years later, we can see how that turned out. It almost worked.

Trump drove up turnout of his supporters to a level beyond what seemed possible in 2016, winning 74 million votes in his reelection effort. The strategy failed because he also drove up turnout of his opponents, motivating many of the 81 million who voted for Biden.

Biden has taken a very different road. In his first day in office, he rescinded the travel ban, which was widely unpopular. And he took several other steps to dismantle signature parts of the Trump legacy. Mostly, however, he’s focused on a suite of proposals — more support for vaccinations, an increase in the minimum wage, money to help schools reopen — that have bipartisan appeal.

At the same time, he has steered clear of several demands of his party’s activists. He avoided wading into a fight over whether to abolish the Senate filibuster, for example, a primary goal of Democratic progressives, and he’s declined several times to take a position on whether the Senate should convict Trump at next month’s impeachment trial.

Where Biden starts

What do opinion polls tell us about the public mood which provides the context for Biden’s actions?

Start with two key findings from a poll that Reality Check Insights, a California-based survey firm, did earlier this month in partnership with The Times.

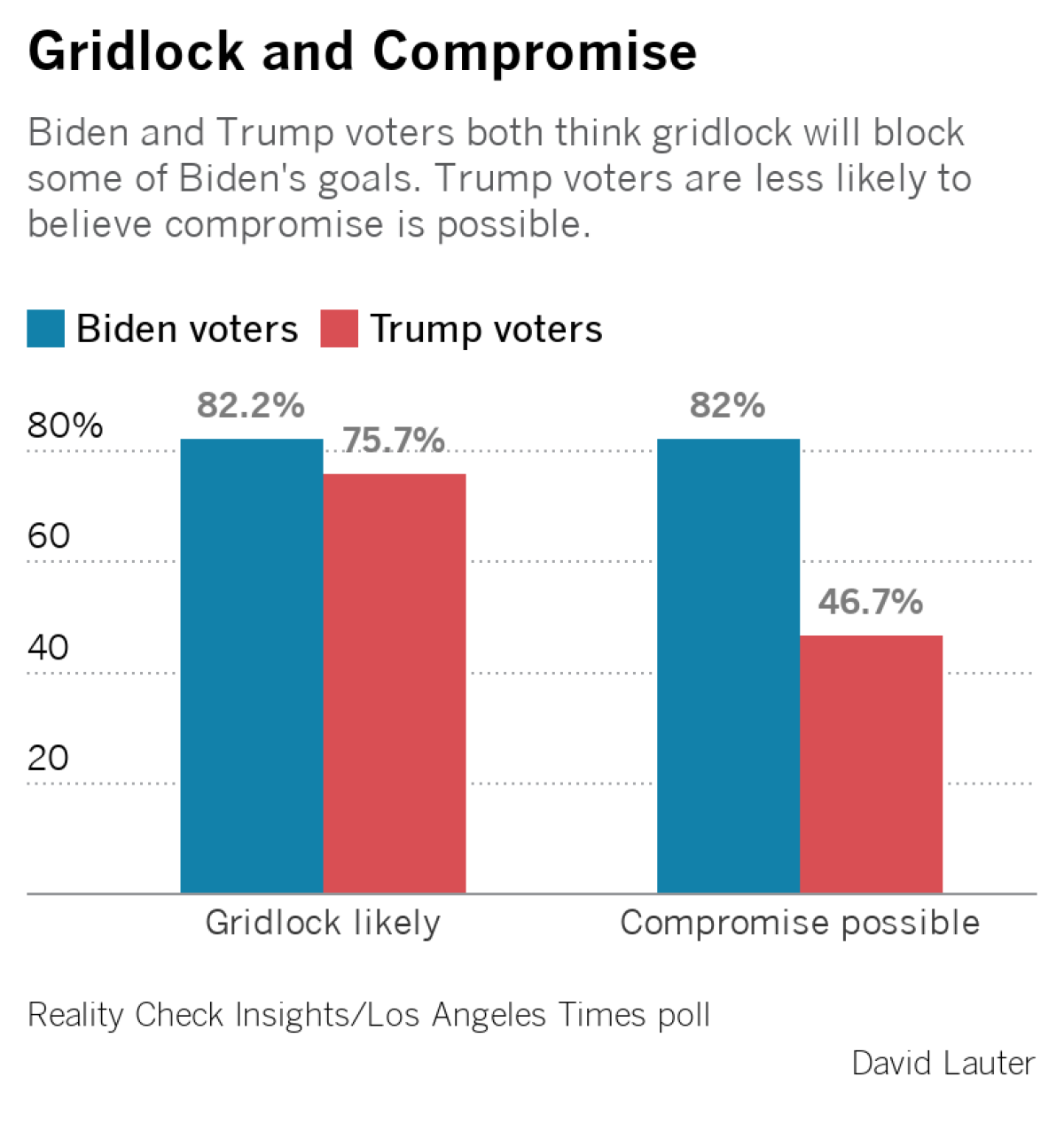

The poll found that the public begins with fairly modest expectations for what Biden will be able to achieve. About three-quarters of Americans said they definitely or probably “expect partisan gridlock and polarization in Washington will block the Biden administration from achieving its goals.”

The Times partnered with Reality Check Insights, a California-based survey firm, to poll public opinion nationwide. Here’s how the poll works.

That view was shared widely across the partisan divide. Among Trump voters, 33% said they thought gridlock definitely would block Biden’s goals, with another 43% saying it probably would. Biden voters didn’t disagree much — 28% said they expected gridlock to definitely block Biden, while 54% said it probably would.

Belief in the power of gridlock remained fairly consistent across lines of race, education, income and gender, a testament to the lessons Americans have learned from a generation of unrelenting partisan warfare in Washington.

Where the two sides differed, however, was in their view of compromise.

The poll asked Americans whether they would say it is “possible to compromise and find common ground with people who disagree with you or would you say this is not possible?”

By 82%-18%, Biden voters said they believed compromise was possible. By 53%-47%, Trump voters said they believed it was not.

That gap, which shows up in other public opinion surveys, too, tells a lot about the two parties and helps explain the very different approaches taken by the two presidents.

Biden’s frequent emphasis on bipartisanship and unity no doubt reflects his deep beliefs about the country and about how to use power in a democracy, just as Trump’s insistence that “I, alone, can fix it” and his repeated refusals to accept deals reflected elements of his personality. But both presidents also have responded to what their voters wanted.

Trump’s core supporters eschewed compromise; they wanted a president who would fight. Biden’s believe compromise is possible and want the president to pursue it — or at least to try.

All week, Biden has played to that sentiment. Progressive activists took to social media to argue that Biden should stop talking about bipartisanship and move directly to passing his $1.9-trillion COVID relief package through Congress using Democratic votes, alone; the White House continued to say that Biden hoped to attract Republican support.

Even as Democratic leaders began making preparations to push the measure through using the budget procedure known as reconciliation, which would allow the bill to pass the Senate without any Republican votes, White House press secretary Jen Psaki told reporters that reconciliation didn’t mean giving up on bipartisanship: Republicans, too, could vote for a reconciliation bill, she reminded them.

“There’s no blood oath anybody signs. They’re able to support it regardless” of the parliamentary procedure used, she blithely noted.

Republicans, pointing to the Democratic preparations for a potential party-line vote, have started to say that Biden’s talk of unity is merely a smokescreen to hide partisan maneuvers. So far, however, that argument hasn’t gotten much traction beyond the party’s own supporters. That’s in part because none of the Republicans have stepped forward to offer a compromise they’d actually vote for.

Next week, both houses are scheduled to vote on a budget resolution, the first step in the reconciliation process. After that, committees will work up the actual language of the package, which the House could take up in late February and the Senate shortly afterward, once it has finished Trump’s impeachment trial. The goal is to get a bill to Biden’s desk by early March before expanded unemployment benefits expire on March 14. The relief package would extend those benefits.

Assuming that Biden can keep Democrats united behind him — and since his proposal hews carefully to issues that almost all Democrats agree on, there’s a good chance he will — that would give him a significant early victory. And, unlike Trump’s early move, Biden’s victory would come on issues that rank high on the priority list for most Americans.

A new survey from the Pew Research Center found that 80% of Americans said strengthening the nation’s economy should be a top priority for the president and Congress; 78% said dealing with the coronavirus should top the priority list. And even though Republicans (63%) were less likely than Democrats (90%) to rank the coronavirus as a top issue, it was near the top for both parties.

Biden starts out with about 54% of Americans approving of how he’s doing his job and 35% disapproving, according to the average compiled by the fivethirtyeight.com website. That’s significantly better than Trump, who never got to 50%; not as good as President Obama, who began with approval in the 60% range; and about where Presidents Reagan, Clinton and George W. Bush stood early in their presidencies.

Reagan’s approval rose over his first several months in office as he scored some early victories. Clinton, by contrast, lost ground quickly as a series of partisan battles, some early defeats and a general appearance of disarray led many voters to decide he wasn’t quite ready for the job.

Biden sold himself to the public as an experienced hand who promised he could make the machinery of government work after a long period in which many Americans had begun to doubt that was still possible. Ultimately, his ability to get the coronavirus under control likely will matter more than anything else in whether he realizes that promise. But if he wins his initial big legislative package while convincing the public that he was open to compromise when possible, he will have taken a big first step.

GOP struggles with post-Trump identity

The legacy of the Trump administration has continued to leave the GOP with an identity crisis, Janet Hook reported. The party’s divide between Trump loyalists and those who want some distance from the former president was on display this week from Washington, where senators took a test vote on Trump’s impeachment trial, to Wyoming, where Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.), an ardent Trump supporter, spoke at a rally against Rep. Liz Cheney (R-Wyo.), the third-ranking member of the Republican House leadership.

An early test of strength will come in Virginia, Hook wrote. Party leaders are hoping to block state Sen. Amanda Chase, who likes to describe herself as “Trump in high heels,” from becoming the Republican nominee for governor.

Virginia Republicans have been largely shut out from power in the state in recent years as the voters have moved left and the party has moved right. Party leaders fear Chase would worsen that pattern; she argues that it’s the establishment that has failed.

Meantime, in Washington, Republicans have drifted back toward Trump on the issue of holding him accountable for his role in inciting the attack on the Capitol earlier this month.

As Jennifer Haberkorn wrote, the prospect of Trump being convicted in his impeachment trial has all but vanished. Only five Republican senators voted against him in this week’s vote, which came on an effort by Sen. Rand Paul to block a trial on grounds that the Senate can’t try a president once he’s no longer in office.

Paul’s effort failed, 55-45, so the trial will go ahead, starting Feb. 9.

David Savage examined the question of whether the Senate can convict Trump of incitement based on a speech. The short answer: Yes, whatever 1st Amendment rights Trump might be able to claim in a criminal proceeding wouldn’t help in an impeachment, which is a political process “designed in part to remove high officials whose words, as well as their deeds, amounted to an abuse of power or responsibility,” as Savage wrote.

Finally, Mark Barabak looked at whether Trump can rehabilitate his reputation and some lessons from Richard Nixon’s partially successful efforts to do so.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

The latest from California

Gov. Gavin Newsom continues to face the threat of a possible recall. As of earlier this week, the recall campaign had submitted 720,000 signatures — about half of those needed to qualify the measure for the ballot. Of those, about 410,000 had been verified.

The recall effort has a wide range of supporters, but as Anita Chabria and Paige St. John reported, some are far-right groups, including QAnon and virus skeptics whose links to the recall are causing headaches for other supporters of the anti-Newsom effort.

But the Newsom administration’s own problems have also fueled the opposition. One of the most egregious trouble spots is the state’s broken unemployment agency, which continues to fail at getting help to hundreds of thousands of people who qualify for assistance, as Patrick McGreevy reported.

Another persistent problem involves the state’s efforts against the COVID-19 pandemic. This week, Newsom picked Blue Shield to oversee the state’s vaccination efforts, as Melody Gutierrez and John Myers reported.

Barabak looked at some good and bad news for Newsom from an expert on recalls: The state’s polarized politics make it a decent bet that the recall will qualify for the ballot, but also that Newsom would ultimately beat it, says Joshua Spivak.

Stay in touch

Send your comments, suggestions and news tips to politics@latimes.com. If you like this newsletter, tell your friends to sign up.

Until next time, keep track of all the developments in national politics and the Trump administration on our Politics page and on Twitter at @latimespolitics.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.