Essential Politics: Is protesting outside justices’ homes an invasion of privacy or good politics?

WASHINGTON — Outrage on the left erupted within minutes of publication last week of a draft Supreme Court opinion overturning Roe vs. Wade, the landmark opinion that guaranteed a woman’s right to abortion.

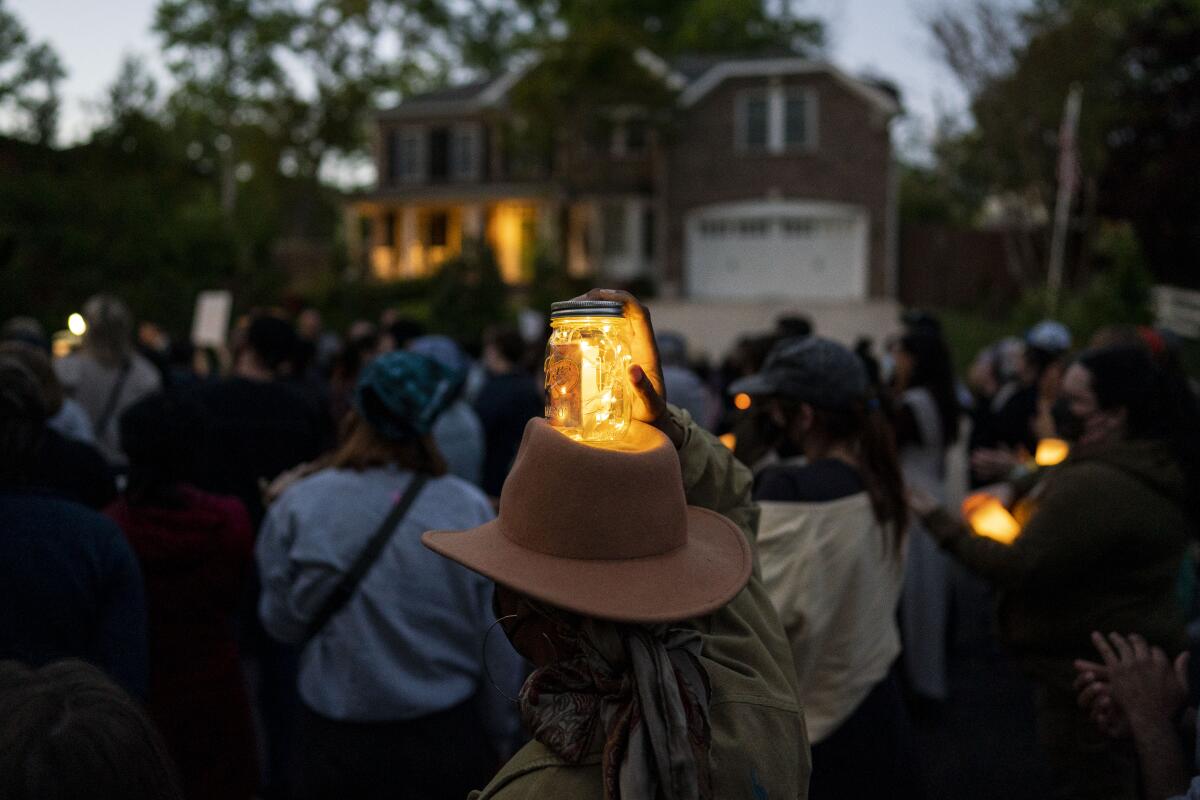

That night, protesters, armed with signs and bullhorns, flocked to the high court, and officials soon ringed the historic building with an unscalable fence. Undaunted, protesters turned their attention closer to home — chanting slogans as they strode past the residences of the conservative justices in the Washington suburbs.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

For some, particularly members of the Washington establishment, those protests crossed a line and were an invasion of privacy. Protesters, they argued, should have kept their chants and cheers directed at the justices’ workplace and away from justices’ families and tidy lawns. This raises two questions: Did they go too far? And are such protests ever effective?

Hello besties, I’m Erin B. Logan, a reporter with the L.A. Times. I cover the Biden-Harris administration. Today, we are going to talk about the efficacy of protesting outside the homes of prominent Washington policymakers.

Chants, chalk and outrage

On Saturday evening, protesters gathered under umbrellas in front of the homes, located in Montgomery County, Md., of Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justice Brett Kavanaugh, chanting “keep abortion safe and legal” and “no uterus, no opinion.” Using pink chalk, they sketched the outlines of wire hangers on the sidewalk, drawing attention to how women conduct do-it-yourself, unsafe abortions where the procedure is outlawed.

Through the genteel, residential neighborhoods, they carried a variety of edgy signs, including one that read, “Don’t like me at your house? Get out of my uterus.”

The protests seemingly expanded Monday evening at the northern Virginia home of Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., who authored the draft opinion. Organizers marched in Alito’s neighborhood and, in an announcement, said the vigil needed to take place at his residence “because it’s been impossible to reach him at the Supreme Court.”

Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) on Saturday reportedly called the police after a pro-abortion rights message was written in chalk on the sidewalk in front of her home in Maine, according to the Bangor Daily News.

Neither Collins nor the Supreme Court responded to a request for comment.

The backlash to these protests was swift — especially on the right.

Former White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer called for the arrest of activists, claiming they broke the law. On the Senate floor, Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky said “trying to scare federal judges into ruling a certain way is far outside the bounds of 1st Amendment speech or protest.”

Top Democrats also expressed frustration. White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki tweeted that while President Biden “strongly believes in the Constitutional right to protest,” judges “must be able to do their jobs without concern for their personal safety.” On Monday, the evenly split Senate unanimously agreed to expand security for justices.

While party leaders shunned the demonstrations, liberals and progressives on Twitter defended them.

Racial justice activist DeRay Mckesson tweeted that Trump’s supporters “literally broke into the United States Capitol building, had their feet propped up on [House Speaker] Nancy Pelosi’s desk, had Congresspeople hiding in closets — and they want to tell us that we can’t stand on the sidewalk outside of Kavanaugh’s house? Nah.” Another user tweeted that if Kavanaugh “doesn’t like the pro abortion protests outside his house, he can simply drive or relocate to a different state. right?”

Our daily news podcast

If you’re a fan of this newsletter, you’ll love our daily podcast “The Times,” hosted every weekday by columnist Gustavo Arellano, along with reporters from across our newsroom. Go beyond the headlines. Download and listen on our App, subscribe on Apple Podcasts and follow on Spotify.

Will these work?

This isn’t the first time people have protested at the homes of powerful policymakers.

In 2004, hundreds went to the home of Karl Rove, then a top advisor to then-President George W. Bush, and urged him to back the DREAM Act, a proposal that would legalize the status of some undocumented immigrants. In 2010, amid the housing bubble, hundreds protested at the home of Gregory Baer, then general counsel for Bank of America, over the role big banks played in rampant mortgage foreclosures and destabilizing the American economy.

Such “home” demonstrations were occurring with enough frequency in the 1980s and early 1990s that Montgomery County, a leafy Washington suburb where many politicos and officials live, banned picketing at private residences. (The law, reportedly passed specifically in response to animal rights activists protesting outside the homes of medical researchers, allows demonstrators to march, without stopping, down residential streets.)

In the short term, the protests outside justices’ homes will not move the political needle, said Fletcher McClellan, a political scientist at Elizabethtown College. The demonstrations “show the nation what stakes are involved” but they are “not going to get the justices to change [their] minds,” he said. “I think their minds have been made up really for quite some time.”

The protests, however, can easily be perceived as distracting, as they enable people, “especially those who are in favor of the Alito opinion, to change the subject,” McClellan said.

While that is happening, calls for civility are not changing the demonstrators’ minds. They just don’t care. Alito’s “intrusion into our bodies, into our healthcare and his egregious theft of our rights deserves an equally dramatic response,” a protester said Monday night, according to video footage.

In the long term, however, these protests may help spur more organization within the pro-choice movement, McClellan said. “The anti-abortion movement has been very well organized for a long time, and now pro-choice people realize that they very well may lose a right, they’re going to be mobilizing in the coming months,” McClellan added.

The war in Ukraine

— On Sunday, as air raid sirens wailed in Kyiv and in cities and towns across Ukraine, First Lady Jill Biden made a foray into the embattled country, meeting her Ukrainian counterpart near the Slovakian border, according to Times writers Laura King and Courtney Subramanian. The day also saw another high-profile visit, from Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who traveled to a suburban town outside Kyiv where evidence has emerged of atrocities committed by Russian troops.

— The U.S., European Union and Group of 7 leaders on Sunday unveiled a fresh round of sanctions targeting Russia’s industrial sector, state-controlled media and Russian and Belarusian finance executives, Times writer Courtney Subramanian reported. The G-7 also vowed to phase out or ban the import of Russian oil, a move that European leaders have so far resisted but that was proposed by the EU last week.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

The view from California

— California lawmakers say they are troubled by state Controller Betty Yee’s behind-the-scenes advice to a politically-connected company seeking a $600-million no-bid government contract to provide COVID-19 masks, prompting calls for a second legislative hearing to examine the failed deal, Times writer Melody Gutierrez reported. Yee’s role in California’s scuttled state contract with Blue Flame Medical LLC went undisclosed for two years, despite a lengthy legislative inquiry and federal investigation.

The latest on the campaign trail

— Money has played an unprecedented role in this year’s Los Angeles mayoral race, with nearly $40 million pouring in from contributions and loans, the most to date, Times writers Sandhya Kambhampati and Iris Lee reported. Billionaire developer Rick Caruso has given his campaign $25 million, more than any other candidate in the race. However, most mayoral candidates are relying on money raised through political contributions

— A Georgia judge on Friday ruled that Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene is qualified to run for reelection to Congress, concluding that voters who challenged her eligibility failed to prove that she had engaged in insurrection after taking office, the Associated Press reported. But the decision will ultimately be up to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger.

The view from Washington

— The Army must put more money and effort into repairing poorly maintained and substandard housing for military service members and their families, U.S. senators demanded Thursday, amid persistent reports that mold and other issues threaten troops’ health, the Associated Press reported. One after another, members of the Senate Armed Services Committee pressed top Army leaders during a hearing to spend money on military housing in their states.

Sign up for our California Politics newsletter to get the best of The Times’ state politics reporting. And don’t forget to follow me on Twitter for updates about my adorable dog Kacey and to share pictures of your adorable furbabies with me at erin.logan@latimes.com.

Stay in touch

Keep up with breaking news on our Politics page. And are you following us on Twitter at @latimespolitics?

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get Essential Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to politics@latimes.com.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.