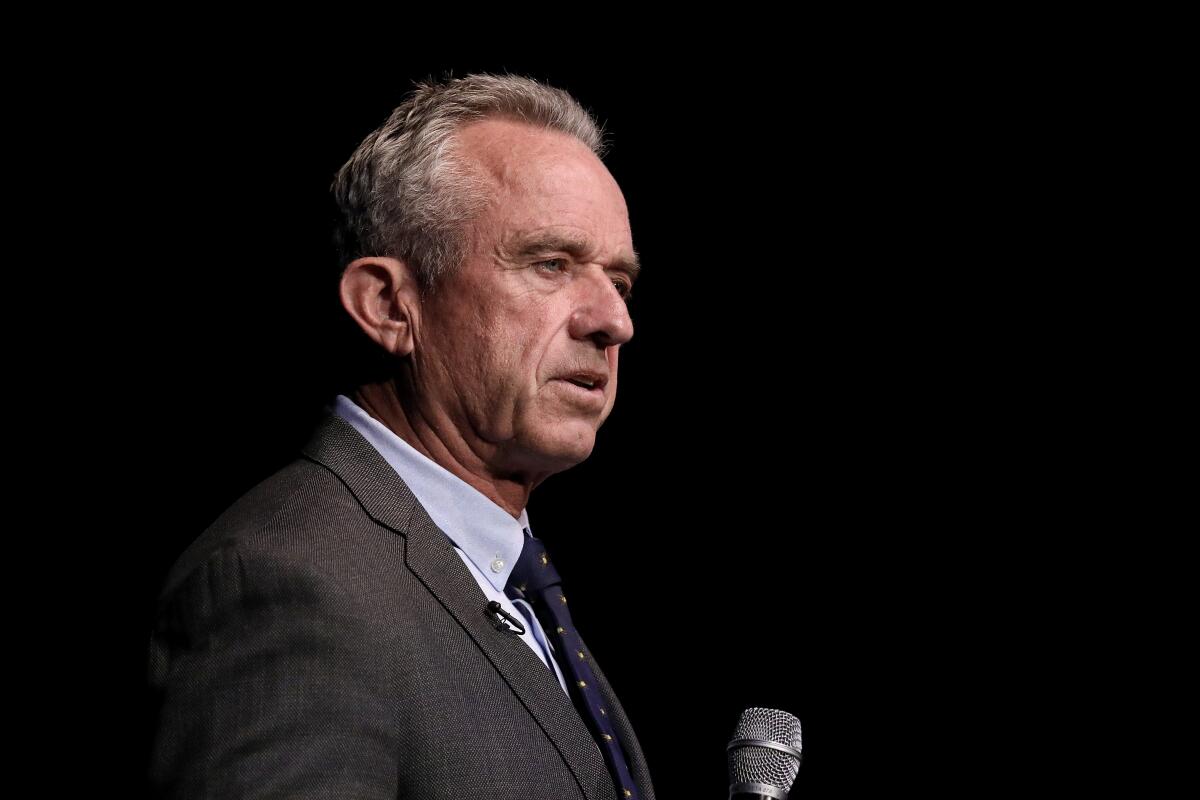

RFK Jr.’s third-party threat: Does it hurt Biden or Trump more?

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Tempted to make a bet on the rematch between President Biden and former President Trump?

There are a lot of reasons that would be a bad idea. Here’s a big one — Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Polls, pollsters and pundits disagree about how much support Kennedy has — or even which candidate he potentially would hurt more.

The Trump and Biden campaigns, however, seem more in agreement: They’re both acting as if Kennedy poses a small, but significant threat to Biden’s reelection.

You're reading the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Anita Chabria and David Lauter bring insights into legislation, politics and policy from California and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

They’re probably right.

An exceedingly close contest

With the election now just over six months away, the vast majority of voters, probably about 9 in 10, have made up their minds. Only a handful of states are truly in doubt. But those locked-in voters and states are evenly balanced between the two sides.

Within the closely divided states, the sliver of the electorate who remain uncertain about which candidate they will vote for — or whether they’ll vote at all — will be critical to the outcome.

A newly released study by the Pew Research Center finds that 91% of people who voted for Biden last time and 94% of those who voted for Trump plan to vote for the same person this year. Registered voters who did not cast a ballot in 2020 are almost evenly divided, Pew found.

So it’s not surprising that over the past year, the race has fluctuated only within a very narrow band.

In most polls during the first half of last year, Biden led by a small margin. Trump took a small lead in surveys during the last few months of the year, which he held until early spring.

Now, Biden appears to have regained some ground, especially among his fellow Democrats, and the race appears to be back to a dead heat, at least in national surveys.

One thing hasn’t changed: A lot of voters don’t like this choice. That’s especially true of less partisan voters. In theory, the unpopularity of both Biden and Trump provides an opening for a third-party or independent candidate.

Whether Kennedy is well positioned to take advantage of that opening is unclear.

Gauging Kennedy’s support

One reason it’s hard to guess how much support Kennedy will win this fall is that polls have a hard time measuring how much support he has now.

The most recent Quinnipiac University national poll for example, showed 16% of registered voters saying they would support Kennedy if the election were being held today. Several other surveys have shown results in a similar range.

By contrast, the Economist/YouGov poll, also released this week, pegged Kennedy’s support at just 3% among registered voters.

The wide variation underscores the problem pollsters face in measuring Kennedy voters. His backers come from both the left and the right and disagree widely on many issues. What most of them share is disaffection from the political system. Disaffected people are inherently hard to poll — they tend not to readily respond to surveys — and hard to predict in terms of turnout.

Another big challenge: We don’t know whether Kennedy will be on the ballot in all, or even most, swing states.

Kennedy got access to his first swing-state ballot, Michigan, earlier this month, when the state’s Natural Law Party — a one-person operation that has maintained itself on the ballot for two decades — agreed to give its slot to him and his running mate, Nicole Shanahan.

Utah and Hawaii have also placed Kennedy on their ballots. Unlike Michigan, neither state is remotely in contention.

Shanahan’s large fortune means that Kennedy likely will have the money to run petition drives in other states, but the outcome won’t be known until later this year.

Even small vote totals can matter

In the vast majority of U.S. elections, third-party and independent candidates fade as the election approaches. Some exceptions exist: Ross Perot received just under 19% in 1992 — the high point for an independent — but that came in an era when partisan loyalties were much weaker than today.

But in a close race, a third-party candidate needn’t get double-digit support to change the outcome.

Ralph Nader may well have cost Al Gore the election in 2000, for example, by swinging the outcome in Florida: He won 97,488 votes there, about 1.5% of the state’s total, and Gore lost the state by fewer than 600 disputed ballots.

In 2016, candidates other than Trump and Hillary Clinton took 5.6% of the vote, with most of that going to Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson and the Green Party’s Jill Stein. In three swing states, Stein’s total exceeded Trump’s margin.

It’s impossible to know how many of Stein’s voters might have voted for Hillary Clinton, but the claim that she cost Clinton the election is at least plausible.

In 2020, by contrast, all the independent and third-party candidates combined took less than 1.8% of the vote.

Which side does Kennedy hurt?

Kennedy, of course, has a famous Democratic name. But surveys have given mixed results on whether he would siphon more support from Biden or Trump.

“His role and who he takes votes from is likely to be quite dynamic” as the campaign develops, said Lis Smith, the veteran Democratic strategist who leads the party’s efforts against Kennedy.

Recent polls have shown Kennedy getting more support from the Republican camp, which could be “a function of our getting the word out about him,” Smith said. That has included a public endorsement of Biden earlier this month by 15 members of the Kennedy family.

The latest NBC News poll, for example, asked voters two horse-race questions. First, it asked about a Biden-Trump matchup and found Trump ahead 46%-44% — a result well within the survey’s margin of error.

Then the pollsters asked about a five-way race involving Biden, Trump, Kennedy, Stein and Cornel West, the philosopher and political activist. In that matchup, Biden led by two points — 39%-37%.

Kennedy picked up 15% of those who had chosen Trump in the two-way matchup and 7% of those who had chosen Biden, giving him 13% overall, the poll found.

Ideologically, that makes some sense: Kennedy’s anti-vaccine theories, which form a key part of his platform, may appeal more to the political right than the left.

Some of his other views also clearly wouldn’t sit well with groups of Democrats who are disenchanted with Biden, especially those on the left.

In an interview last month with Reuters, for example, Kennedy strongly supported Israel and expressed skepticism about a cease-fire in Gaza. Every previous cease-fire “has been used by Hamas to rearm, to rebuild and then launch another surprise attack. So what would be different this time?” he said.

In an interview late last year, he referred to the Palestinians as “pampered by international aid organizations.”

But the bulk of voters who are attracted to Kennedy aren’t activists. They skew young, but also tend to be less focused on politics and less likely to vote at all, polls show.

Smith says the “most effective message” for moving those voters away from Kennedy is simply that “he’s a spoiler for Donald Trump.”

“He was encouraged by Trump allies,” including Steve Bannon, Trump’s former top strategist, and “is being propped up” by big Trump donors, like Timothy Mellon, the banking heir who is by far Kennedy’s biggest contributor. Mellon, 81, has given $20 million to Kennedy’s super-PAC, American Values 2024, and has also given tens of millions to Republicans, including $16.5 million over the past two years to Trump’s Make America Great Again PAC.

Democrats have also zeroed in on Kennedy’s equivocal statements on abortion, including one in August in which he said he would sign a national ban on abortions after 15 weeks. His campaign later disavowed that statement.

Republicans have no equivalent to Smith’s operation

The difference reflects the strategic calculations of the two campaigns.

Trump’s campaign isn’t premised on winning a majority, something a Republican has managed only once in the past eight presidential elections, (George W. Bush in 2004).

Trump took 46% in 2016 and 47% in 2020. His campaign’s best bet is to sufficiently hold Biden’s vote down in the key swing states to allow 46% or 47% to prevail. That scenario requires third parties to win a significant vote.

By contrast, Biden, who won 51% of the vote last time, knows that Trump’s core vote is solid. Rather than try to chip away at Trump’s total, his goal has to be to get past him.

Kennedy stands as a threat to that. How serious that threat will be is one of the great unknowns of the current campaign.

WHAT ELSE YOU SHOULD BE READING

This week’s must read: Big cities, including Los Angeles, have stopped bleeding population; urban America appears to be coming back from its pandemic-era slump.

Poll of the week: Pew took a deep look at Americans’ foreign policy priorities.

The L.A. Times special: The treatment of miscarriages is upending the abortion debate, Seema Mehta writes.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.