News Analysis: Kamala Harris drops out. What went wrong?

Kamala Harris quickly made the most of her national role when she arrived in the U.S. Senate three years ago, electrifying Democrats as an assertive antagonist toward the incoming Trump administration. That self-assurance set the foundation for her presidential run.

But her forceful demeanor belied the risk-averse approach to politics that she’d long established in California. Those competing instincts were among the main obstacles blocking her quest for the Democratic nomination. On Tuesday, Harris abandoned the campaign.

In the end, she lacked a central reason to run, beyond ambition and a notion — expressed by advisors and others close to the senator — that now was her moment, and she should seize it. A core argument for her candidacy or a deep set of convictions would have lent ballast to her campaign. Instead, voters would repeatedly walk away from events enthused about Harris, but wondering what she believed in and stood for.

“The problem ultimately was one of rationale and purpose,” said Paul Maslin, a Democratic consultant with a long track record in California politics. “Who was she? Why was she running? I don’t think it was clear.”

The daughter of a breast cancer researcher from India and an economist from Jamaica, Harris, 55, had plenty of attributes to make her a singular political figure, not least her racial background and relative youth in a crowded Democratic field dominated by white septuagenarians. Her career as a former California attorney general, San Francisco district attorney and violent-crime prosecutor in Oakland offered law-and-order credentials that, in theory, could play well in a general election against President Trump.

But her candidacy was felled by the enduring strength of former Vice President Joe Biden’s support among African Americans. As a woman of color running to be commander in chief, she was especially burdened by the fraught politics of race and gender. A poorly structured campaign gave way to infighting and public feuding.

With Kamala Harris’ departure from the race, the Democratic field has lost a prominent black candidate. The top four candidates now all are white.

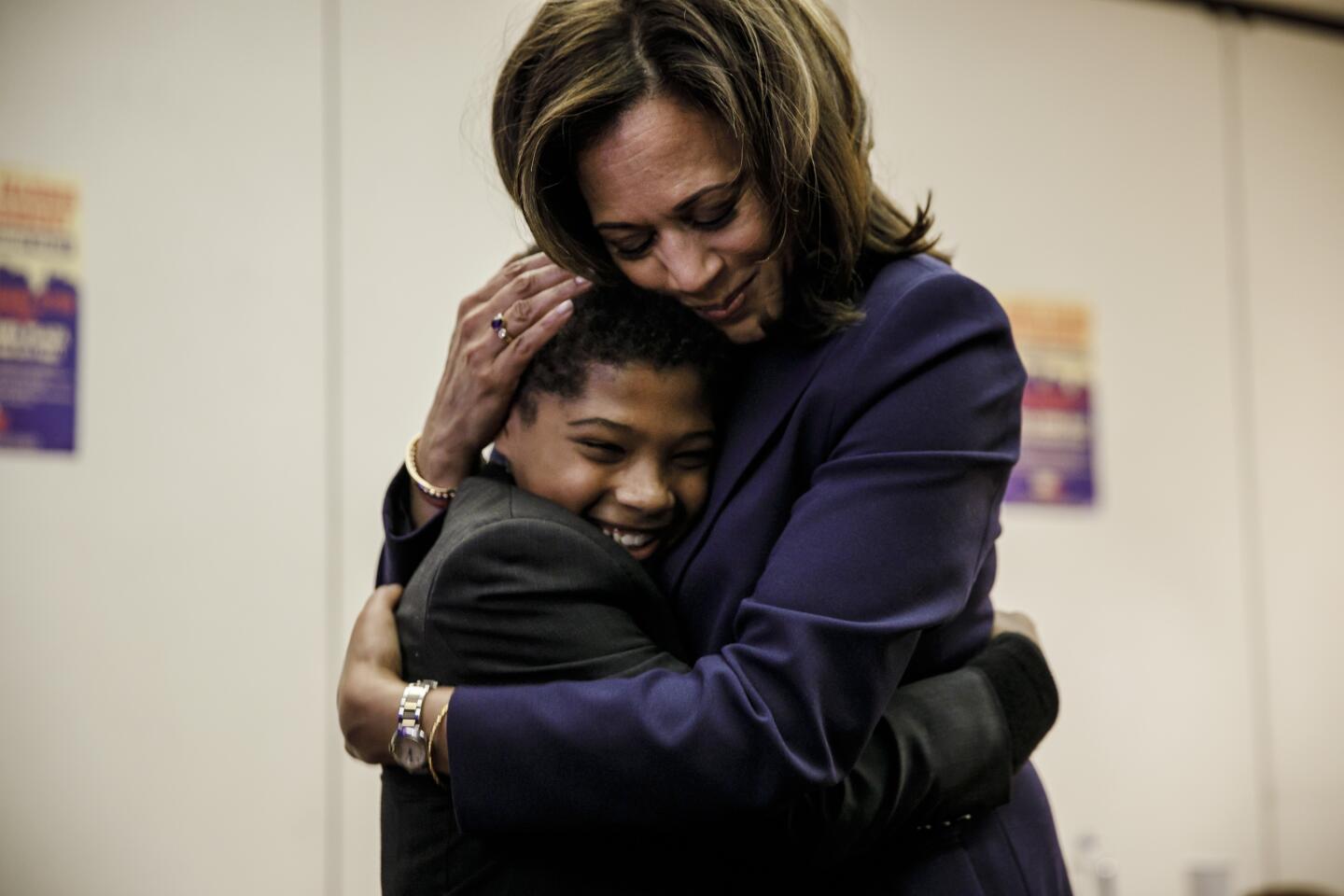

Her failings aside, Harris was to a considerable extent a victim of these political times and the obsession Democrats have with defeating Trump. She was an inspiration to many voters, especially African American women, who were thrilled by the promise of her candidacy.

But this is no time for idealism, many said, suggesting the country was too racist and misogynist to elect anyone but an establishment white male — a cold-eyed calculation that has worked to Biden’s benefit.

Ultimately, though, her campaign ended because of the most common of reasons: lack of money. After a holiday weekend in Iowa of trying to chart a path forward amid growing challenges, Harris made the decision on Monday to quit the race and announced it to supporters in an email on Tuesday morning.

“I’ve taken stock and looked at this from every angle, and over the last few days have come to one of the hardest decisions of my life,” she wrote.

Underscoring how hastily the end had come, a super-PAC formed by former Harris aides had just begun spending $1 million on television advertising in Iowa when the news broke. The group immediately canceled the ad buy.

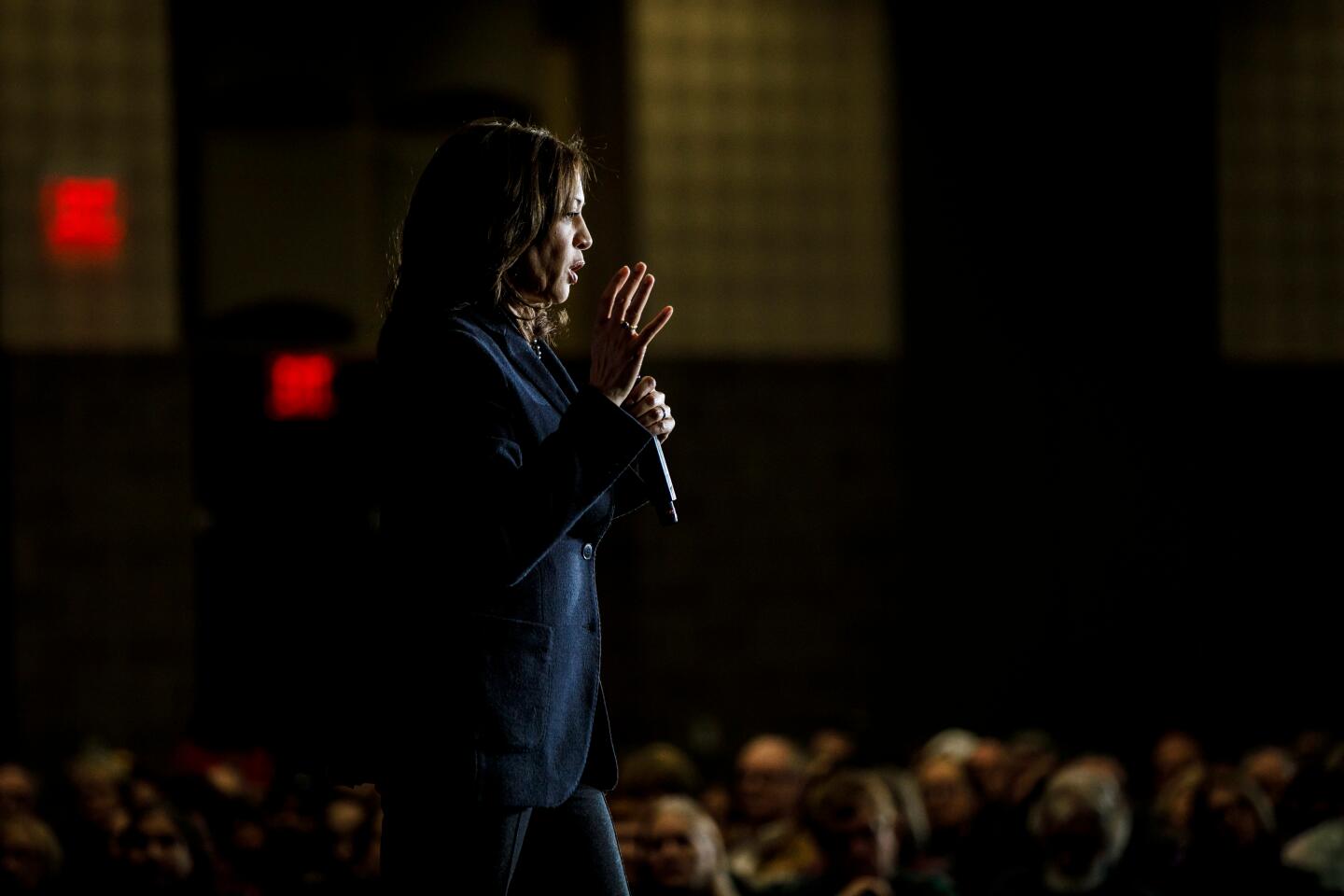

The TV spot focused on what made Harris a national star: her lacerating questioning of Trump appointees in Senate hearings. Voters often cited those moments on the campaign trail, relishing the idea of Harris similarly eviscerating Trump in the general election. Harris herself argued she was best fit to prosecute the case against Trump.

“I have taken on Jeff Sessions, I’ve taken on Bill Barr, I have taken on Brett Kavanaugh,” Harris said in her final Democratic debate. “I know I have the ability to do that.”

California Democratic voters, by a wide margin, wanted Sen. Kamala Harris to drop out of the presidential race, a new poll found.

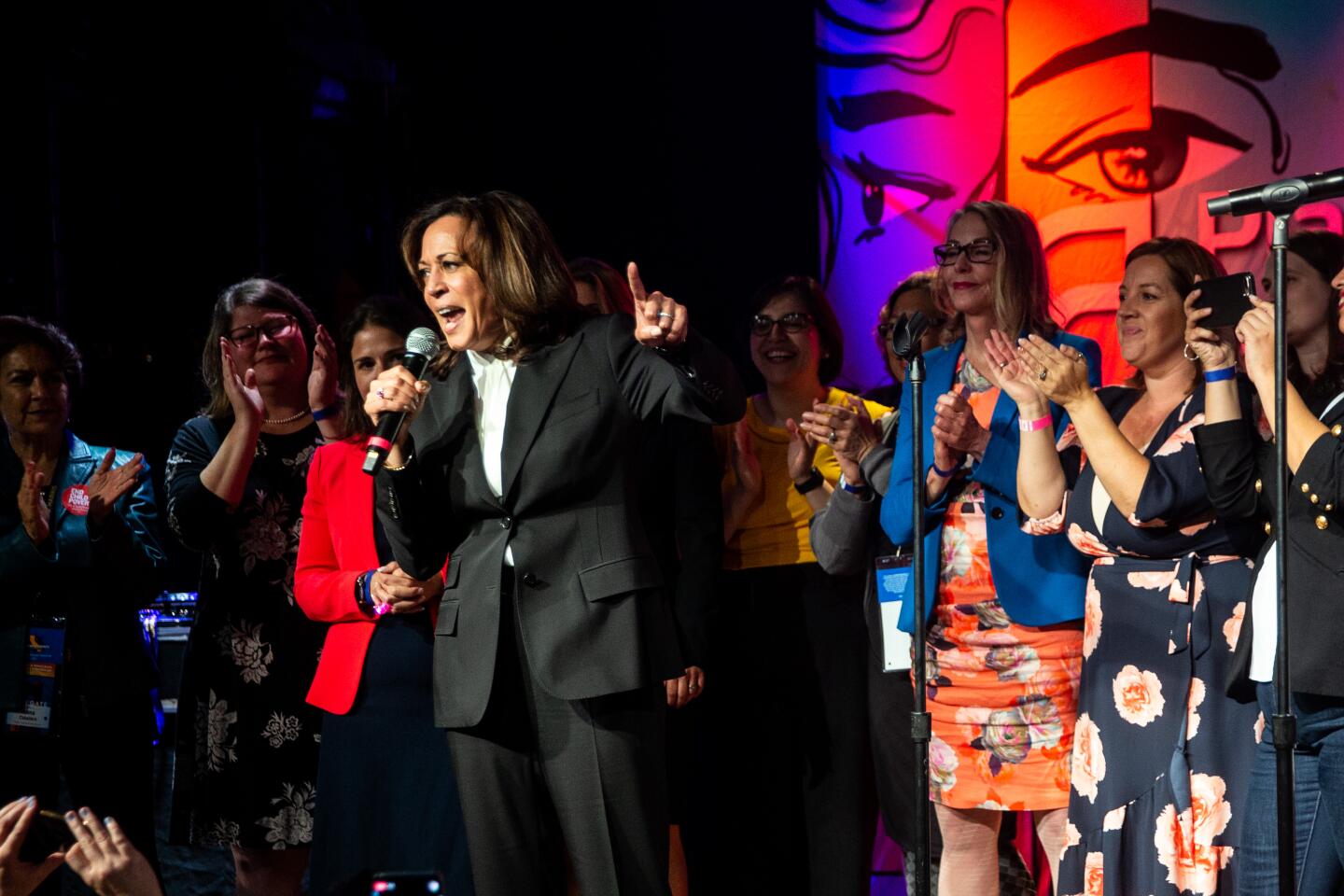

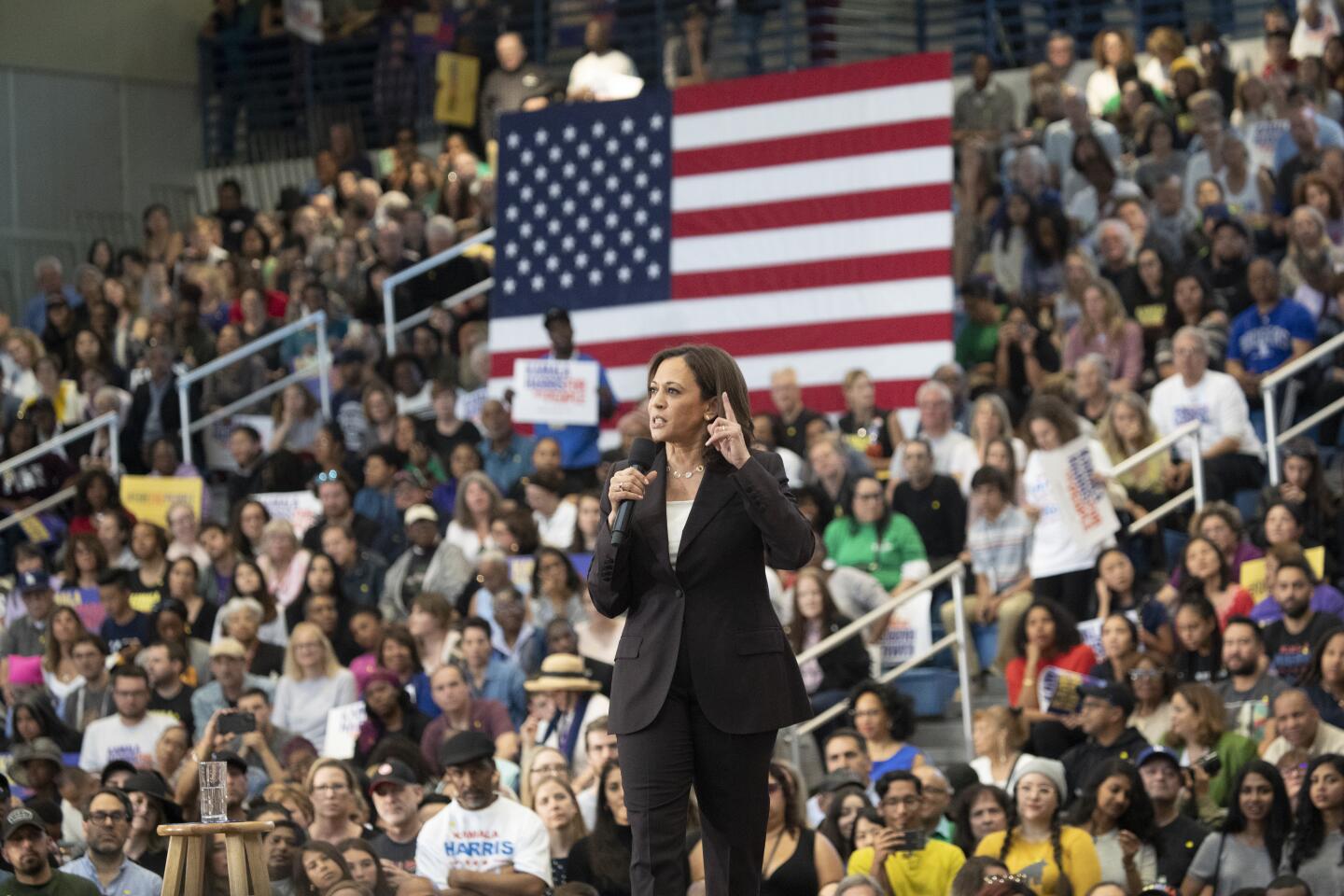

Throughout the campaign, Harris distinguished herself best in tightly choreographed settings, such as her flashy launch rally in downtown Oakland before more than 20,000 people.

Most consequential was her deftly executed takedown of Biden in the first Democratic debate over his fight against mandatory school busing as a U.S. senator in the 1970s. Her emotionally charged recollection of being bused across Berkeley as a young girl to a mostly white elementary school left the former vice president nearly speechless. Her poll numbers spiked afterward.

“I thought that campaign was really going to take off from there,” said Aimee Allison, founder of She the People, an advocacy group promoting women of color in politics.

But in the following days, Harris lost the moral high ground as she mangled answers to questions about whether busing would remedy today’s racial inequities in education.

For longtime Harris watchers, the lost momentum was symptomatic of a mushiness that predated the 2020 campaign. In California, Harris’ cautious instincts meant she lacked a strong public presence on controversial issues of the day, particularly on criminal justice matters.

In her 2016 Senate race, Harris branded herself as “fearless,” a purposeful attempt by her campaign to compensate for perceived timidity.

Aides say Harris shed some of her bet-hedging tendencies in the Senate as she took on Trump with heated rhetoric. In a hyper-partisan Congress, she was free from the tightrope she’d walked as attorney general in clashes between law enforcement and civil rights groups.

Still, Harris’ reluctance to take bold stands in California hobbled her entire presidential run. A few days before her Oakland rally, the New York Times published a damaging op-ed by Lara Bazelon, now a law professor at the University of San Francisco, who faulted Harris for opposing criminal justice reforms or staying silent as they were debated.

“It was deeply problematic for her to use the word ‘progressive’ to describe her prosecutorial record, because it was so profoundly inaccurate,” Bazelon said Tuesday.

If Harris had described herself as “a pragmatic law-and-order centrist,” Bazelon said, that would have been consistent with the “fairly conservative, cautious positions she took as D.A. and attorney general.”

While detractors saw waffling, supporters described her style as deliberate and steeped in preparation.

“The bar was higher for her, as a woman and a person of color,” said John A. Pérez, former California Assembly speaker, who advised her campaign.

One of her biggest missteps was on healthcare. Harris was an early backer of “Medicare for all,” aligning herself with the party’s progressive flank. After she flippantly said she would do away with private insurance during a CNN town hall, her campaign offered confusing explanations. She ultimately released a plan that embraced aspects of Medicare for all, but allowed for some private insurance. The plan came under attack from both progressives and moderates.

The campaign’s disorganization was reflected in its ever-shifting mottos (“For the people,” “Justice is on the ballot” and “Dude gotta go,” alluding to Trump) and messages, at times contradicting each other. Harris rejected her progressive opponents’ calls for big structural change, emphasizing instead a “3 a.m. agenda” of solutions to pocketbook worries that keep Americans up at night. But she also proposed eliminating the Senate filibuster to pass a $10-trillion climate change program.

Some of the mixed signals were due to strife among her campaign staff, insiders said, including a disagreement between Harris’ sister, Maya, the campaign chairwoman, and other senior aides on how to navigate the senator’s criminal justice record. The operation was structured with two heads — Maya Harris and campaign manager Juan Rodriguez, who is also a partner in the consulting firm run by her top advisors — which slowed decision-making.

“As a candidate, she had all the right attributes, and in the moments a campaign doesn’t fire on all cylinders, candidates and their campaign infrastructure have to share in that responsibility,” Pérez said.

Harris often boasted that she had never lost an election, but the massive scale of a California campaign can be hard to translate to the small states with early presidential contests.

“Iowa and New Hampshire are the anti-California,” said Don Sipple, a strategist for former Gov. Pete Wilson’s ill-fated 1996 presidential run. “You have to develop a relationship where you sit in people’s living rooms, you attend coffee klatches eight or 10 times, where they get to know you. That doesn’t happen in California.”

Not all of Harris’ troubles were self-inflicted. The campaign originally was planned around a strong showing in South Carolina, where black voters exert tremendous influence. But Biden has maintained solid support among black voters, to the detriment of Harris and New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, the remaining black candidate in the race.

“Biden has most of them, and the ones he doesn’t have were not automatically going to go to Harris or Booker just because they are black,” Maslin said.

The ascendance of Pete Buttigieg, the little-known mayor of South Bend, Ind., undercut Harris’ strength with big-money donors. Susie Tompkins Buell, a top San Francisco fundraiser for Democrats, was an early supporter of Harris, but also was drawn to Buttigieg.

“He is showing great leadership by the effectiveness and harmony in this campaign,” Tompkins Buell said Tuesday. “He started slowly and has steadily developed and grown. It has felt organic. Kamala burst on the scene and couldn’t sustain.”

As Tuesday drew to a close, a Harris aide posted a video on Twitter of the former candidate dancing in her Baltimore headquarters with campaign aides.

Harris, looking more lighthearted than she had in weeks, shimmied and sang along as a Beyoncé song played. Its title: “Before I Let Go.”

Times staff writers Mark Z. Barabak and Seema Mehta contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.