How do Democratic debate candidates plan to combat climate change?

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Wildfires, rising seas and rollbacks by the Trump administration that undermine California’s authority to pursue pioneering environmental policies have put climate change top of mind for the state’s Democratic voters. Every one of the party’s presidential candidates has a robust climate action agenda.

It is a rare area in this primary where candidates are marching mostly to the same beat. They almost universally support a Green New Deal. They all vow to immediately reenlist the U.S. in the Paris accord to fight global warming. Each of them would scrap all of the Trump rollbacks and set a firm deadline for moving the nation to net zero emissions, the point at which any greenhouse gas emissions caused by humans are balanced by carbon sinks in the environment or technologies that remove carbon from the atmosphere.

The differences lie in how far, how fast and how much to spend. Are they calling for the phaseout of all fossil fuels by a certain date? Do they see nuclear energy as part of a zero-emissions future? Are they looking to immediately ban fracking? We break down where they stand and what climate policy would look like under the vision offered by each of the seven Democratic hopefuls in the December primary debate scheduled for Thursday in Los Angeles.

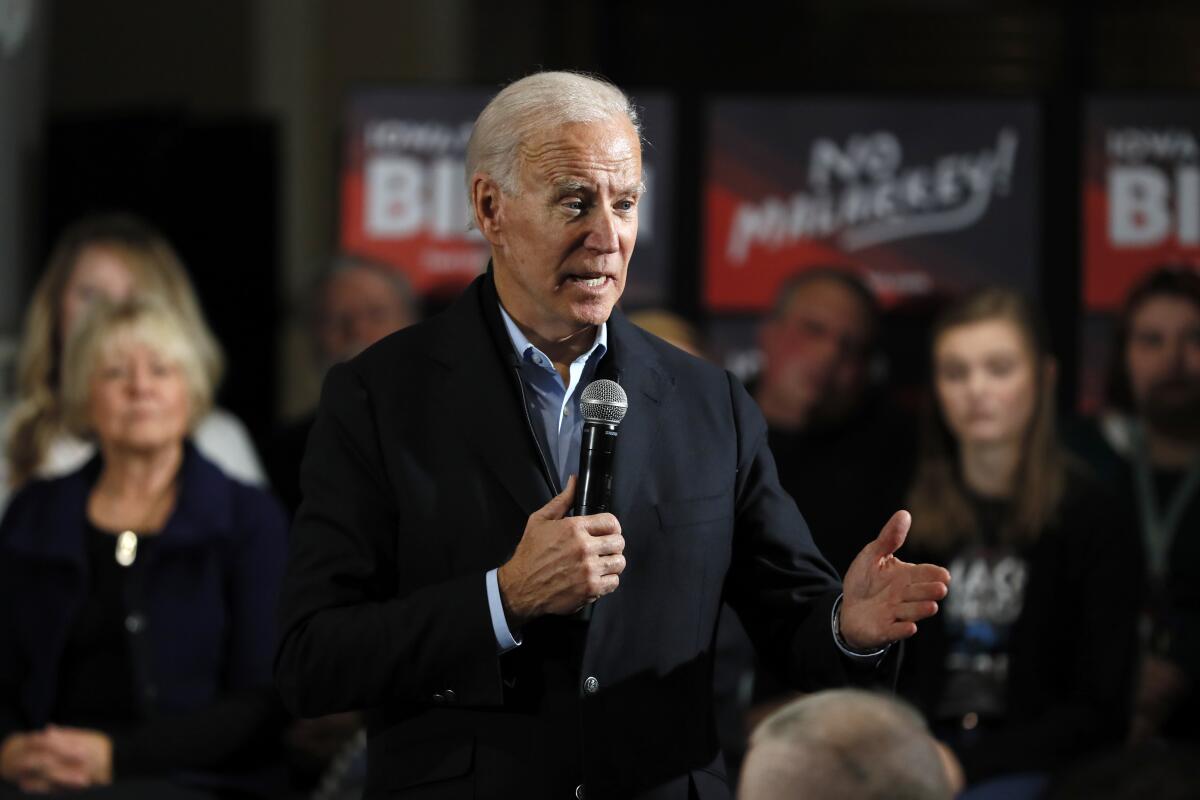

Joe Biden

Former Vice President Joe Biden unveiled a bold $1.7-trillion plan for climate action that belies his brand of “incremental” progressivism. It doesn’t go as far as some of his rivals, but the Biden vision is hardly incremental.

During the Obama administration, Biden was at the forefront of pushing the world to embrace bolder climate action and the Paris accord on global warming. Faced with a hostile Congress, the Obama White House moved forward with aggressive administration actions aimed at cleaning up power plant emissions and moving the nation’s vehicle fleet toward significantly higher fuel efficiency.

Biden recognizes that the Obama plans were ambitious but also that merely picking up where the last Democratic administration left off would not fully address the urgent warnings of climate scientists. He is calling for much further-reaching action and arguing that his deep experience in diplomacy makes him uniquely qualified to reposition the U.S. as the world leader in confronting global warming.

“On day one, Biden will sign a series of new executive orders with unprecedented reach that go well beyond the Obama-Biden Administration platform and put us on the right track,” the candidate’s plan vows.

Pete Buttigieg

Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind., takes a more measured approach to reaching net zero emissions than some of his more progressive rivals.

The target dates he sets are bold, but Buttigieg does not set down markers for eliminating fossil fuels altogether, and he relies on technologies and tax incentives that some environmentalists argue could slow the transition to carbon-free energy. Yet it is unmistakably a bold plan that recognizes the urgency of the climate crisis.

The amount of spending Buttigieg is committing to is vague in the plan, though the campaign has estimated it would add up to at least $1.5 trillion. A linchpin of it is spreading investments in clean technology and resiliency to the parts of the country, such as the industrial Midwest, that Buttigieg says too often get left behind when government embarks on ambitious program expansions. The plan emphasizes inclusion of farm communities.

“For too long, rural America has been ignored in the climate conversation — or worse, told that whole regions and ways of life are a part of the problem,” Buttigieg’s plan says.

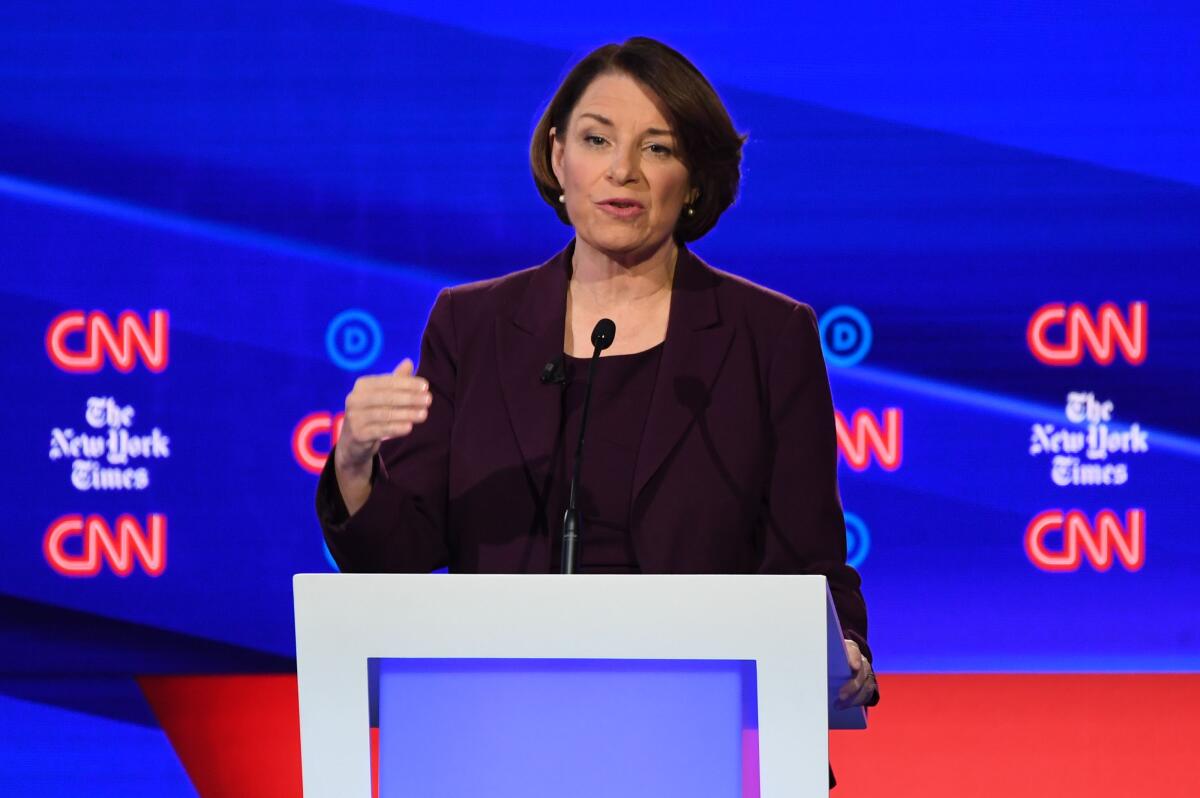

Amy Klobuchar

Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar is running as a moderate alternative to the progressive firebrands in the race. As such, her climate plans are more modest than those of some of her rivals.

Klobuchar seems to chafe at the multitrillion-dollar price tag and the radical transitions mapped out in the Green New Deal as proposed by its original drafters. The government spending she talks about is in the hundreds of billions, not trillions, of dollars.

The senator says she supports the Green New Deal ideas more as things to aspire toward than as workable, concrete plans. She favors development of advanced nuclear energy technologies and pollution-capturing innovations that could allow a future for the coal industry in a green economy.

“As the granddaughter of a miner who worked 1,500 feet underground, Senator Klobuchar understands the hard work and sacrifice of those who built and powered our country,” the Klobuchar climate plan says. “She is committed to supporting and creating new opportunities for workers and communities that have depended on the fossil fuel industry.”

The Klobuchar agenda looks more like a resumption of the Obama-era climate policies than the shift toward the much more aggressive climate action that many candidates are promoting. But Klobuchar is also a longtime ally of climate activists, and she talks frequently on the stump about restoring the voice of science in federal decision making and has authored clean energy legislation in the Senate.

Bernie Sanders

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders self-identifies as a democratic socialist and prides himself on advancing the most far-reaching and aggressive plans in several major policy areas. Climate is no exception.

The Sanders plan has the biggest price tag at $16.3 trillion over 15 years, the biggest expansion of government and the most ambitious targets. He sets an end date for fossil fuels. And the spending he outlines for investment in green technology, natural resource protection and expansions of public land dwarfs that proposed by any other candidate.

The blueprint most closely reflects the goals laid out in the Green New Deal as drafted by progressive firebrand Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Sen. Edward J. Markey of Massachusetts.

Whereas other candidates talk about creating a few million jobs, Sanders is talking about 20 million. He is calling for cuts in military spending and “massive” tax hikes on fossil fuel income. There would be big investments in everything from high-speed rail to resiliency programs focused on such things as fighting wildfire and drought.

Sanders promises that “climate change will be factored into virtually every area of policy, from immigration to trade to foreign policy and beyond.”

Tom Steyer

California billionaire Tom Steyer launched his political career as a climate activist. It has been quite a rebranding. When he was a hedge fund manager, Steyer was heavily invested in the fossil fuel companies that he is now angling to put out of business. But since leaving his old industry, he has put his money where his mouth is.

Steyer has spent heavily on state ballot measures to promote efficiency and clean energy. His organization NextGen America blanketed the country with canvassers and advertising campaigns aimed at finding and mobilizing “climate voters.”

He has been more engaged on the climate issue than most of his rivals. But many of them have now embraced the talking points Steyer was promoting years ago, leaving him with a climate plan that has enjoyed effusive praise from mainstream environmental groups but doesn’t necessarily stand out at this moment when other candidates are offering equally bold visions.

“My plan will first and foremost ensure communities have the tools, training, and dedicated resources to lead the clean energy and healthy climate transformation from the ground up,” Steyer writes in the blueprint, which would invest some $2.3 trillion in federal dollars toward fighting climate change.

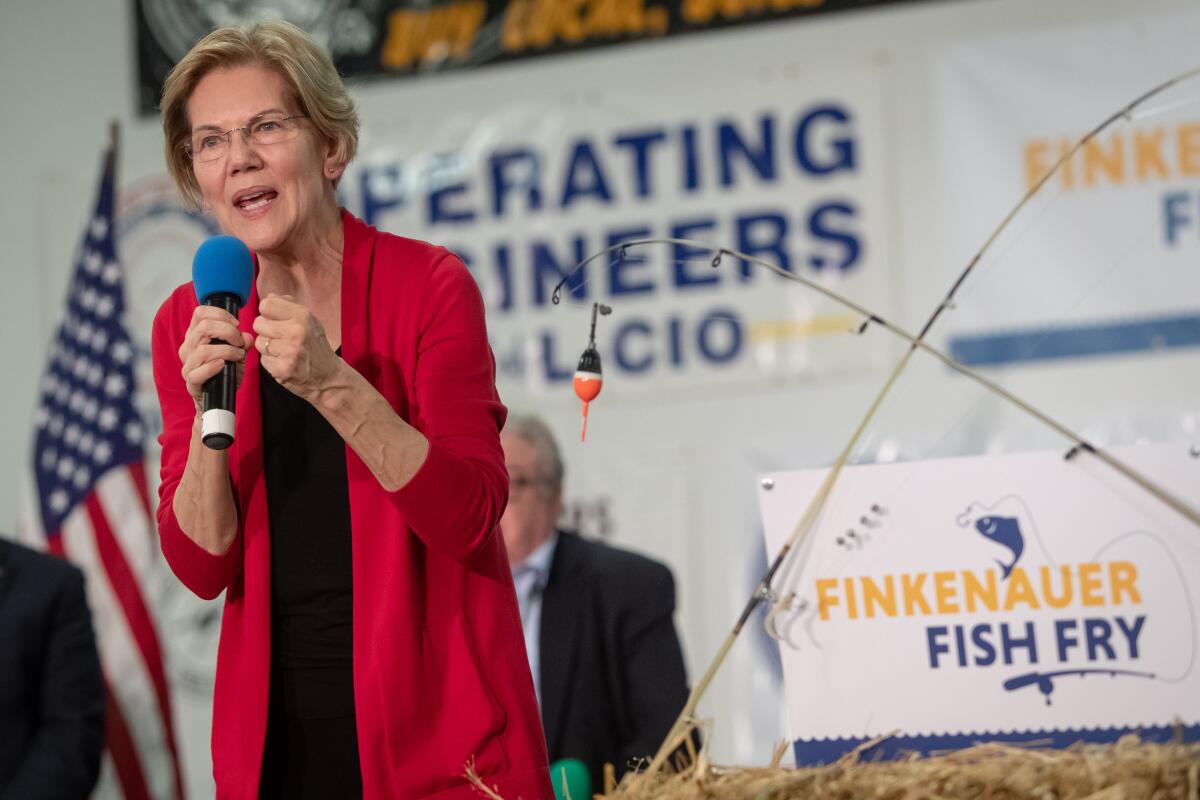

Elizabeth Warren

Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s climate plan is very much in step with her broader brand. It calls for big government investment and takes aim at what she says is corruption in the energy economy.

“To really bend the curve on climate, we’ll need sustained big, structural change across a range of industries and sectors,” the plan says.

Warren was the first candidate to vow to stop new drilling on public land in the first day of her administration, and she is an enthusiastic proponent of the Green New Deal. She was also the first candidate to sign the No Fossil Fuel Money Pledge, rejecting campaign contributions from fossil fuel companies.

Warren argues that her broader anti-corruption plans will “end lobbying as we know it” and remove the clout fossil fuel companies hold over the nation’s energy policies.

Her investment in green energy is geared toward creating new union jobs in the sector. She vows to spend at least $3 trillion, with a third of it going to “front-line communities” to “remediate” what she says are historic environmental injustices.

Andrew Yang

New York entrepreneur Andrew Yang sets aggressive goals for zeroing out emissions, but he proposes a path to getting there that is very different than his rivals.

“We can’t dismiss any ideas — especially not those that have support from the scientific community — or rule anything out because it doesn’t fit our ideological framework,” his blueprint for climate action says.

It includes plans that do not sit well with some large environmental groups, such as increased reliance on nuclear energy and engaging carbon “capture” technologies that trap emissions and store or repurpose them.

Yang would spend $4.87 trillion over 20 years, with more than half of it going to finance loans for “household investments in renewable energy.”

Where the Democratic candidates stand ...

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.