Will Democrats tear up the script for their final debate of 2019?

- Share via

After five rounds of debate, a fleeting set of viral moments and enough soundbites to fill a large concert hall, the Democratic race for president stands largely where it was six months ago, when the year’s first face-to-face meeting took place on a soupy night in Miami.

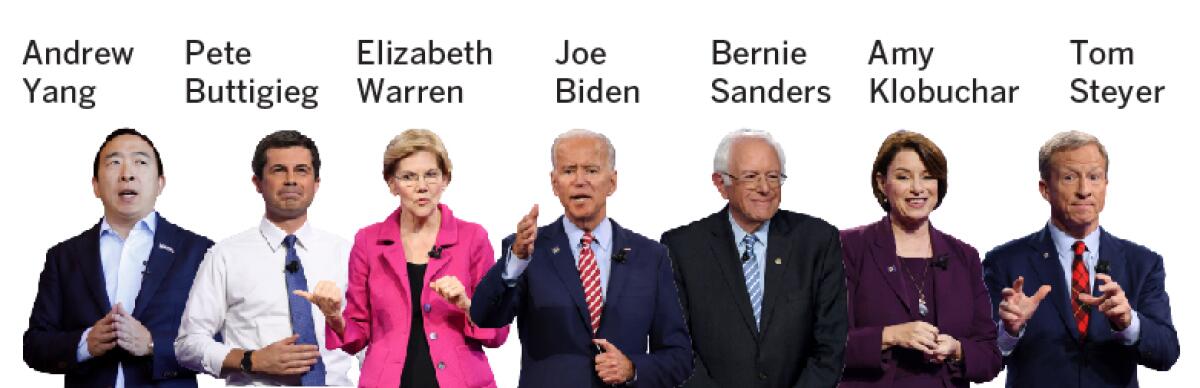

The final debate of 2019 will air Thursday night, live from Los Angeles, with the smallest number of participants to date: just seven candidates who met the polling and fundraising requirements set by the Democratic National Committee. Earlier meetings crammed as many as 12 candidates on stage, or took place over two nights to accommodate a lineup of 20 contestants.

Like a recurring series of TV reruns, the debates have played out with a familiar ensemble, a well-thumbed script and a plot that has varied little from one episode to the next: Will Joe Biden implode before our eyes? Will some little-known candidate remake the contest in a single stroke? Will the stage collapse from the weight of all that political ambition?

“People have gotten more exposure, voters have gotten to know their names and hear their stories and take a bit of their measure,” said Mary Anne Marsh, a Democratic strategist who has stayed neutral in the party’s nominating fight. “But in the end the debates have not in any way upended the top tier, which remains a wildly consistent race between four people.”

Those four — former Vice President Biden, Sens. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg — will be back onstage Thursday night, along with billionaire Tom Steyer, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and tech entrepreneur Andrew Yang.

Though previous debates haven’t altered the contest in a big way — some of the most dramatic moments were staged by candidates, like California Sen. Kamala Harris, who either quit the race or sank into irrelevance — they have not been without consequence.

Candidates in the December Democratic debate want to scrap Trump policies. But where do they differ on healthcare, immigration, climate, gun control and housing?

Sanders, 78, allayed concerns about his health with a robust appearance two weeks after suffering a heart attack. Buttigieg proved himself more than a political flavor of the month by delivering a series of strong and substantive performances.

Warren was forced to flesh out her position on healthcare, one of the major issues in the campaign, after facing repeated prodding under the TV lights. She released a “Medicare for all” proposal that was criticized by some as unworkable and too costly; a follow-up plan was criticized by others as too timid. Since then, Warren’s upward momentum has stalled and her support has even slipped in some early-state polls.

Most significantly, the debates have served to cull the sprawling field, the largest any party has put forth in modern times.

As the benchmarks for qualification grew steeper, winning a place onstage sorted the contestants between those seen as having a shot at the nomination, however meager, and those struggling for attention from voters, donors and the political news media.

“They created sort of a threshold for viability which was very premature,” said Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet, who has been excluded from all but two debates and believes the race is far less settled than opinion surveys suggest.

(An exception has been Steyer, whose spending — north of $50 million and counting — bought the former hedge fund executive a place in the debates by boosting his name recognition and elevating his support in qualifying polls. The race’s other free-spending billionaire, former New York City Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, hasn’t bothered trying to meet the debate criteria, self-funding his campaign rather than building the requisite base of small donors.)

The debates have not in any way upended the top tier, which remains a wildly consistent race between four people.

— Democratic strategist Mary Anne Marsh

The remainder of the 15-candidate field, all except Bloomberg, face a chicken-egg conundrum: A presidential hopeful is denied a turn in the national spotlight, which diminishes his or her stature in the race, which in turn limits their fundraising capacity and support in polls, thus denying them a place on the next debate stage.

And on.

“Instead of assessing the substance of the candidates to decide who should be on stage, we have based it on the ability to spend a bunch of money to make a little money and pop up in opinion polls,” said Sean Bagniewski, chairman of the Democratic Party in Polk County, Iowa, where the traditional means of gaining traction ahead of its caucuses — the first 2020 contest — has been to court voters one speech, one bus tour, one potluck dinner at a time.

“As a result we’re losing people like [New York Sen. Kirsten] Gillibrand and [Montana Gov. Steve] Bullock ... some of the brightest lights of our party,” Bagniewski said, referring to two of the departed candidates, “and it’s real sad.”

Others have objected to a lack of diversity. Last weekend, nine Democratic hopefuls sent a letter to the DNC urging party leaders to change the rules so that candidates of color — specifically New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, who is African American, and former Housing Secretary Julián Castro, who is Latino — could more easily qualify.

A spokeswoman defended the party’s benchmarks, saying candidates were given ample opportunity over the last several months to prove their political wherewithal.

“Our qualifying criteria have stayed extremely low throughout this entire process,” said Xochitl Hinojosa, noting that no candidate polling less than 4% support, one yardstick for December’s debate, has ever gone on to win the nomination. “In addition, we have made diversity a priority by requiring that every debate have women and people of color as moderators. We’ve never seen a political party take this many steps to be inclusive.”

Many of the Democratic candidates for president rarely mention the housing crisis. Some have released bold plans; others have so far promised little or nothing.

If the debates have had a limited impact on the nominating fight, they could take on greater significance come the general election.

Early on, several candidates took positions playing to the left-leaning Democratic base — supporting, for instance, government-provided healthcare for people in the country illegally and favoring civil rather than criminal penalties for unauthorized border crossings — which could prove less appealing to a more moderate general election audience.

Much will depend, of course, on which candidate faces President Trump.

Biden, for instance, recently put forth an immigration plan that omits the call for decriminalizing illegal border crossings. Buttigieg has qualified his stance on Medicare for all, proposing an alternative that would allow individuals to keep their private health insurance if they prefer.

With so many candidates sharing the stage and so many debates still to come — four have been scheduled for January and February alone — it’s hard to know what sinks in and what will be forgotten by the next morning, said Rebecca Katz, a Democratic strategist who has not taken sides in the nominating contest.

“We won’t really know the impact,” she said, “until November of next year.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.