High drug costs outweigh ‘Medicare for all’ as top healthcare issue for voters

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The debate over creating a single government health plan for all Americans may be dominating the Democratic presidential campaign, but most voters are focused on a more basic pocketbook issue: prescription drug prices.

In poll after poll, the high cost of medications is at or near the top of voters’ healthcare concerns, far outpacing interest in moving all or some people into Medicare-like coverage.

That, in turn, is pushing candidates to turn more directly to the issue on the campaign trail in early primary and caucus states, including Iowa, whose caucuses formally kick off the race for the nomination in two weeks.

Several Democratic hopefuls — including Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar — are running television ads in Iowa highlighting their commitment to tackling drug costs.

“You talk to any Iowan, and it is almost certain to come up,” said Anthony Carroll, associate Iowa state director for AARP, the mammoth national advocacy group for seniors, which has made controlling drug prices a top priority. “What I hear from voters is that they can’t afford to wait.”

In one recent poll, two-thirds of Iowa voters identified prescription drugs costs as the most significant healthcare concern, matched only by worries about overall out-of-pocket healthcare costs.

The survey by Morning Consult found similar sentiment among voters in New Hampshire and South Carolina, whose primaries follow the Iowa caucuses.

Similarly, a nationwide poll in September by the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation found that 70% of Americans wanted members of Congress to make lowering drug prices their top priority.

By contrast, just 30% of people said enacting a national “Medicare for all” plan should top lawmakers’ agenda.

“In all our polling over the years, healthcare costs are at or near the top, but it is prescription drugs that are really the salient issue,” said the foundation’s Mollyann Brodie, who has been polling Americans about healthcare issues for more than two decades.

“People are refilling their prescriptions constantly and they see what they’re paying.”

The challenge has become particularly acute for patients as health insurance deductibles soar, forcing growing numbers of Americans to skip care and delay filling prescriptions.

A focus on drug prices is likely to not only resonate with Democratic primary voters, but also to highlight one of President Trump’s major policy vulnerabilities.

Seven in 10 Americans don’t believe Trump is doing enough to lower drug prices, according to a November poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Patients who come to the Havelhöhe cancer clinic in the leafy outskirts of Germany’s capital are often very sick.

Trump made controlling drug prices a key plank of his 2016 campaign, promising to deliver relief to patients by, among other things, allowing Medicare to start negotiating directly with drug companies.

But the president has since reversed positions, rejecting a proposal by House Democrats to give the federal program negotiating authority.

At the same time, several other Trump administration initiatives to rein in prices have stalled or been abandoned, including proposals to restrict rebates that insurers and drug companies often negotiate and to require drugmakers to list prices in television ads.

Three years after taking office, Trump’s proposed regulation to allow importation of lower-priced drugs from Canada and elsewhere is only now being reviewed and may not be finalized for months.

“This is a real albatross for Trump,” said Chris Jennings, a longtime Democratic health policy advisor who worked in the White House under former Presidents Clinton and Obama. “Democrats are well positioned to hold him accountable.”

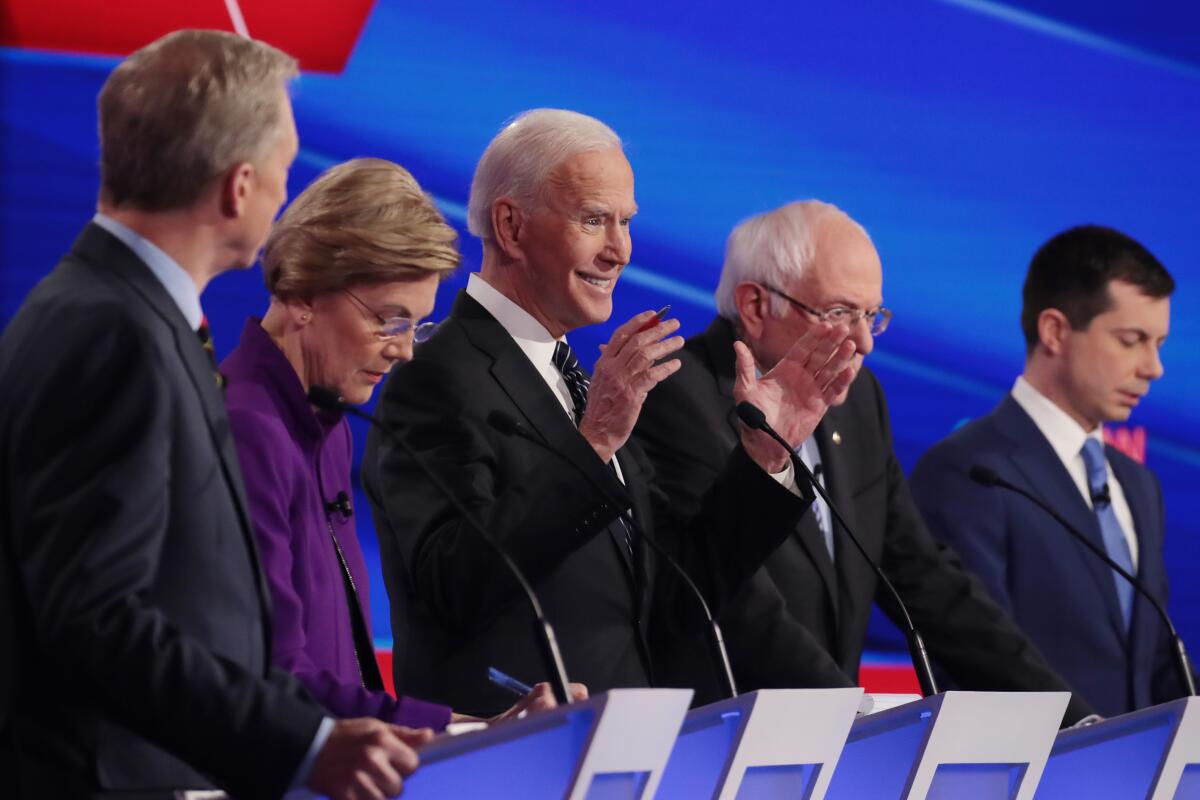

Nevertheless, Democratic presidential hopefuls thus far have spent much more time jousting over their competing plans for expanding Medicare coverage, a pattern that was repeated at last week’s debate in Iowa.

Sanders and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren are pushing plans to move all Americans into a government health plan.

Other candidates, including former Vice President Joe Biden and former South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg, advocate more incremental strategies for expanding health coverage that build on the 2010 Affordable Care Act.

That debate reflects, in part, the fact that Medicare for all remains a major fault line in Democratic politics.

By contrast, there is broader agreement in the party about how to rein in drug prices.

The leading Democratic presidential candidates all support giving Medicare — the government insurance plan for seniors and disabled people — authority to negotiate lower prices with drugmakers. Current law prohibits such negotiation.

This idea is hugely popular among both Democratic and Republican voters. Democrats support Medicare drug negotiations by a 42-percentage-point margin, while support for the idea runs 38 percentage points higher than opposition among Republicans, according to the recent Morning Consult poll.

Many of the Democratic hopefuls favor loosening restrictions on importing lower-priced medications from abroad and taking more aggressive steps to prevent drugmakers from delaying the development of lower-priced generic versions of their drugs.

Several also support new government-imposed caps on how much pharmaceutical companies can charge for their products.

Biden has said he would establish a review board to assess the value of new drugs and recommend a price, a model that has effectively restrained prices in other wealthy countries such as Germany.

Buttigieg said the federal government should revoke patents from pharmaceutical companies found guilty of egregious overpricing.

Warren, who is in a fierce battle with Sanders for support on the Democratic left, has gone further, arguing the federal government should begin manufacturing generic drugs to make cheaper medications available to patients. That competition would put pressure on drug companies to lower prices, she says.

The Massachusetts senator, whose Medicare for all plan stirred intense opposition after she unveiled it last fall, has concentrated markedly on drugs prices in recent weeks.

Asked about her healthcare plans at last week’s debate, Warren didn’t even mention Medicare for all at first, pledging instead to take executive action if elected to cut prices on insulin and other drugs.

When a supporter at a recent town hall in Mason City, Iowa, asked how she would sway voters wary of her sweeping healthcare plan, Warren swiftly steered the conversation toward prescription drugs.

“Let’s start with what’s broken,” she said. “Thirty-six million Americans did not get a prescription filled last year because they couldn’t afford it.”

Klobuchar, who has been a leading advocate in Congress for legislation to curb drug prices, has also made the issue a top-tier item.

And Sanders, whose Medicare for all plan is arguably the signature issue of his campaign, routinely holds up what he calls the corruption of drug companies to assail the failings of the current American system.

“We will take on the greed and the corruption of drug companies,” Sanders pledged at a recent rally in Newton, Iowa.

Having elevated the issue of drug prices on the campaign trail, Democrats now face another challenge: They must convince voters that they will be able to deliver meaningful relief.

House Democrats last month passed sweeping legislation to tackle high prices and give Medicare the authority to negotiate for lower prices on up to 250 medications.

But the pharmaceutical industry retains huge influence in the Capitol, and the bill has been categorically rejected by Republican leaders in the Senate.

It remains unclear if lawmakers will be able to reach a compromise on any major prescription drug legislation this year.

Times staff writers Melanie Mason and Seema Mehta contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.