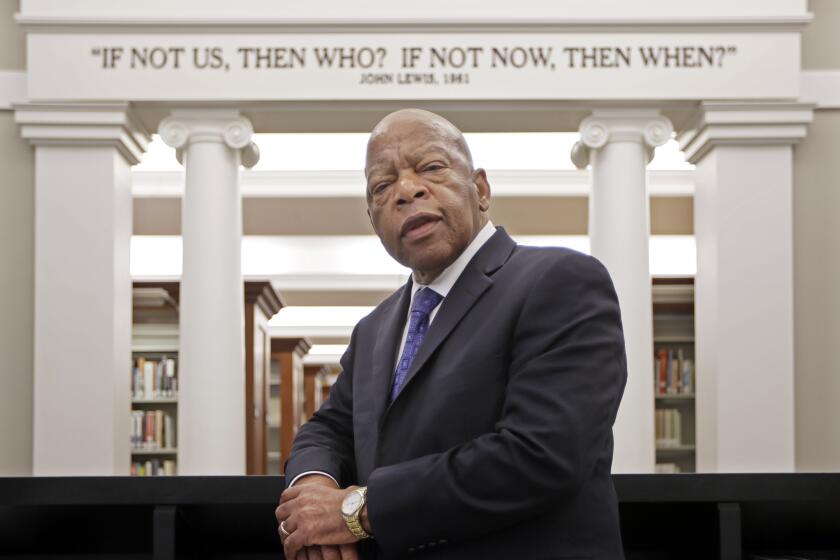

Column: John Lewis’ legacy of good trouble: Building bridges, destroying walls

- Share via

About an hour or so into “John Lewis: Good Trouble,” the documentary begins unveiling some behind-the-scenes details about the 1963 March on Washington and Lewis’ famously fiery speech. Lewis, then 23 years old, had apparently penned remarks so inflammatory that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was concerned enough to request that the event’s youngest speaker lower the temperature.

Lewis made some adjustments to the remarks, which would inspire the hundreds of thousands who had traveled to the nation’s capital that day.

“Get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation,” he said, “until true freedom comes, until the revolution of 1776 is complete.”

As footage of Lewis at the lectern rolled on my TV, I spied another iconic figure directly behind him, smoking a cigarette. It was Bayard Rustin, who is widely credited as a key organizer of the march. Like Lewis, Rustin didn’t mind plucking a few feathers.

“We need, in every community, a group of angelic troublemakers,” Rustin once said.

John Lewis, an icon of the civil rights era and a longtime member of Congress from Georgia, has died.

That sentiment is very much in line with a 2018 tweet Lewis posted that began circulating as news of his death rippled across social media Friday night: “Do not get lost in a sea of despair. Be hopeful, be optimistic. Our struggle is not the struggle of a day, a week, a month, or a year, it is the struggle of a lifetime. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.”

I don’t need to remind you what the country has been experiencing since the killing of George Floyd on the final Monday in May. It’s hard not to notice that the conversations we have studiously avoided are now being had in Klieg-lit prime time. Storytellers inclined to offer a sanitized, reimagined version of America have been replaced by storytellers with a more raw, harder edge. They are not interested in glossing over her scars, her warts, her bloodshed.

A couple of hours before learning of Lewis’ death, I heard a cacophony of car horns and chants as protesters in downtown L.A. once again began blocking rush-hour traffic, led by young people demanding change. They had returned to the streets, brought there by the news that Louisville, Ky., police officers had refused medical attention for Breonna Taylor for more than 20 minutes in mid-March, even as she lay alive after being shot in her own apartment.

This is the part of history that too often gets a good coat of varnish: Comfort doesn’t bring change; only good trouble does. So if you happened to be one of the commuters or pedestrians ensnarled by Friday’s downtown protest, well, good. Demonstrations are supposed to interrupt. Inconvenience. Cause trouble.

King, Lewis, Rustin and the leaders of the civil rights movement understood that if white ears weren’t forced to listen, Black and brown voices would continue to go unheard and demands for change ignored. Besides, you weren’t stuck in traffic because of the protesters marching down Figueroa. You were stuck in traffic because a 26-year-old woman in Louisville was denied her last gasp at life on March 13.

Do not conflate the root cause with the subsequent response.

Do not mistake being nonviolent with being docile.

John Lewis told people, “Never give up, never give in, never give out.” To honor his memory, heed those words, especially when it’s time to vote.

And do not be seduced into reducing Lewis’ life’s work into an optimistic tweet about love and unity without acknowledging what that work really was — making trouble, the kind of trouble that interrupts your regularly scheduled program with an important announcement.

Since the final week of May, I have been heartened by images of multiracial protesters, passage of procedural changes for officers and the confronting of the Confederate flag. My concern going forward isn’t that enthusiasm for change will wane, but in the mistaken belief that change can be effected without causing trouble.

Whether it’s the 11 Southern California professional sports teams that last week announced the formation of a social justice coalition, the Alliance; private sector philanthropists; or elected officials, it’s essential that they accept the importance, and discomfort, of disruption. Good intentions be damned if, to paraphrase Dr. King, they’re driven by a desire to maintain order rather than to seek justice.

Angus Johnston, a historian of student activism and professor at City University of New York, posted a thread on Twitter detailing the moments leading up to Lewis’ speech in Washington nearly six decades ago. One of the tweets shares a passage that was eventually excised from the speech that Lewis gave.

“For the first time in one hundred years,” it read, “this nation is being awakened to the fact that segregation is evil and that it must be destroyed in all forms. Your presence today proves that you have been aroused to the point of action.”

Lewis wasn’t just about helping Black people relax the pain. He was also about ending the hurt. This is why he was such a huge proponent of voting, which he often referred to as our greatest weapon.

So for those team presidents who make up the Alliance, I encourage you to take concrete steps to stop the hurt. That means opening the doors to your dormant stadiums and arenas to serve as polling stations capable of meeting social distancing guidelines. It means using your platforms to denounce policies that are harmful to underserved communities. It means making trouble — good, necessary trouble — which will always be the best way to honor Lewis.

This month, I reached out to a well-connected political friend of mine, asking if he had an address for the congressman so I could send flowers. I had been told about his failing health, and I wanted to say thank you while I still could.

“He’s in good spirits, but it’s nothing to play with,” my friend said, referring to the pancreatic cancer that Lewis was fighting.

“No it is not,” I said. “Man, our heroes….”

“Gotta cherish them while they’re here,” he replied.

I didn’t get the opportunity to send those flowers, something that will follow me the rest of my days. Over the years, I’ve offered my gratitude to Lewis face to face numerous times, but given the current climate — with so many young protesters refusing to allow us to go back to our regularly scheduled programming — I wanted to honor him one more time.

The chants I witnessed in the streets Friday are a huge part of his legacy. As are the reactions: the sound of car horns echoing throughout the streets; the stares coming from irritated, inconvenienced pedestrians who had assumed the protests had ended weeks ago. The traffic.

Trouble.

Considering his last public appearance was to visit the newly installed Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, D.C., I suspect it was the kind of trouble John Robert Lewis would have approved of — the good kind, the necessary kind.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.