Column: Bipartisan agreement, for a change: Trump and Biden share distrust of China

- Share via

WASHINGTON — This year’s presidential race has been dominated by two crises that have upended American lives — the coronavirus and the economic recession — plus vitriolic exchanges over which candidate is most unfit for public office.

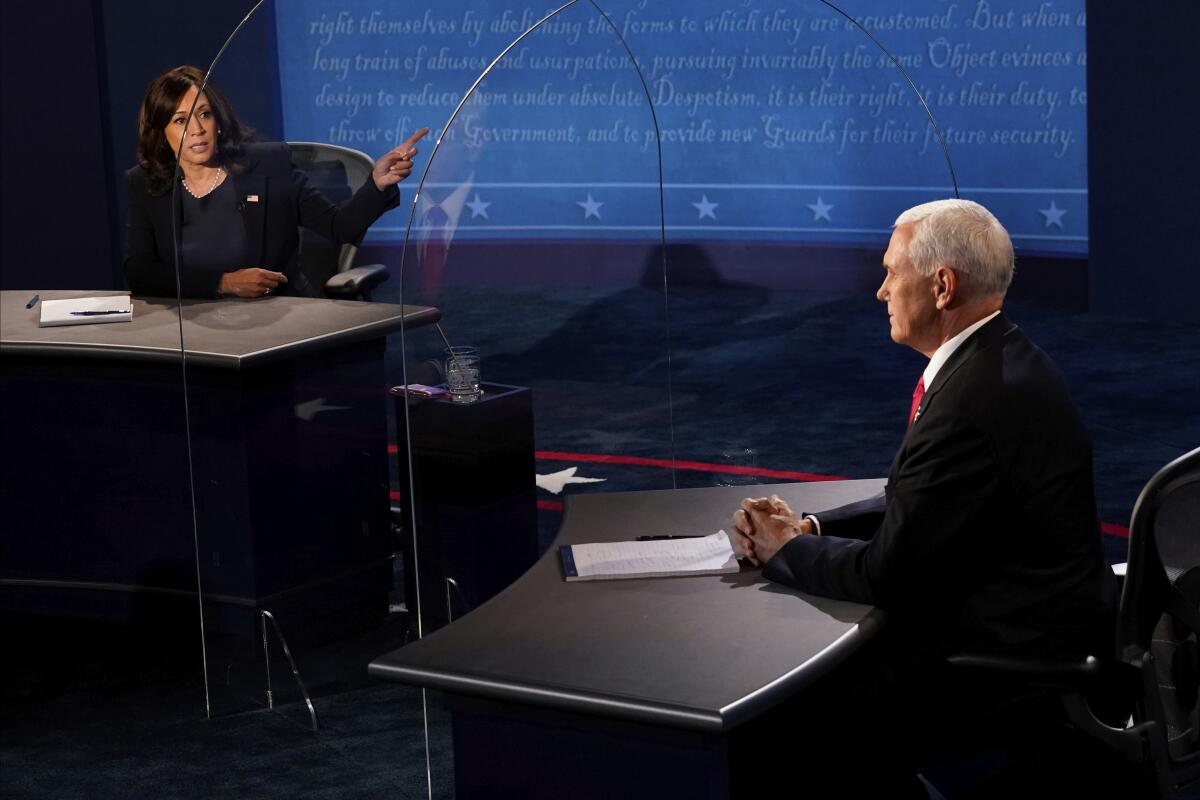

But in Wednesday’s vice presidential debate between Vice President Mike Pence and Sen. Kamala Harris of California, voters were rewarded with a brief, almost civil exchange over the most important challenge in U.S. foreign policy: China.

The two running mates didn’t really disagree about policy. They argued, instead, over who was tougher on Beijing, President Trump or former Vice President Joe Biden.

Trump was on Fox News twice Thursday, Rush Limbaugh’s radio show Friday and let a doctor question him for a faux medical exam on Tucker Carlson’s show.

“The president’s trade war?” Harris asked. “You lost it. … Because of a so-called trade war with China, America lost 300,000 manufacturing jobs.” (That’s inaccurate; manufacturing fell briefly after Trump’s tariffs were imposed, but the estimate Harris cited was for all jobs, not just manufacturing.)

“Lost the trade war?” Pence retorted. “Joe Biden never fought it. Joe Biden has been a cheerleader for communist China.” (That was inaccurate too.)

Score the exchange as a draw.

Trump’s campaign has sought to paint Biden as soft on China, noting his history in the Senate and in the Obama White House of promoting political and economic engagement with Beijing.

A Trump campaign commercial shows Biden, then vice president, with Chinese President Xi Jinping and the charge: “Biden stands up for China.”

Biden fired back with a mirror-image ad that showed Trump with Xi and an accusation: “Trump rolled over for the Chinese.”

It’s not surprising that Trump and Biden are battling over China. That’s what campaigns are for. What’s surprising is how much they agree.

Trump ran for president in 2016 as a braggadocious trade hawk, promising to slap tariffs on China and extract big trade concessions.

Once in office, he instead struck up a bromance with Xi. He called the autocrat “a great leader” and, according to former national security advisor John Bolton, asked the Chinese ruler to buy U.S. soybeans to help his reelection chances.

“He’s for China, I’m for the U.S., but other than that we love each other,” Trump said in January.

Then the coronavirus hit. After U.S. officials concluded that China concealed data on the pandemic, Trump imposed a partial ban on travel from China and blamed Beijing for the pandemic.

By then, Biden had already called Xi “a thug” and called for getting “tough on China.”

“If China has its way, it will keep robbing the United States and American companies of their technology and intellectual property,” he wrote in February.

Biden’s tough talk didn’t hurt his presidential campaign. It also reflected a broader, more important shift by Democrats and establishment Republicans.

Since the 1970s, U.S. presidents have promoted cooperation with Beijing, hoping it would nudge the communist government to become more democratic and to open its fast-growing economy to U.S. companies.

Biden embraced that consensus as a senator and vice president. He sometimes boasted that he had spent more time with the up-and-coming Xi, then China’s vice president, than any other American.

But China’s economy never opened as much as Biden and other advocates of interdependence hoped.

U.S. concerns also focused on Beijing’s growing military might.

Ignoring U.S. warnings, China claimed disputed parts of the resource-rich South China Sea. It dredged runways and harbors and built military facilities on islands and shoals that none of the surrounding nations recognize as Chinese.

“Neither carrots nor sticks have swayed China as predicted,” former Obama advisors Kurt Campbell and Ely Ratner wrote in 2018. Both are now advisors to Biden.

Like the Trump administration, Biden and his aides describe China as a “strategic competitor.”

“On that fundamental point, both parties are in the same place,” Edward Alden, a trade policy expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, told me. “There aren’t extreme differences between them.”

Biden advisors say his administration would strengthen U.S. alliances in Asia to counter China’s military expansion and “change the rules” of the global trading system to alter Beijing’s economic behavior.

Biden might even use some of the same tactics as Trump.

“He’d probably keep Trump’s tariffs in place for some time to use them as leverage,” Alden said. “He’d keep export controls [on U.S. technology] and other sanctions too.”

The differences are mostly on strategy and style.

Trump has acted unilaterally; Biden hopes to revive regional alliances to constrain China.

Biden would be tougher on human rights; Trump has shied away from criticizing Xi’s repressive measures against dissidents and the Uighur Muslim minority.

Biden would seek Chinese cooperation on climate change, a problem Trump has ignored.

Those differences guarantee that Washington’s newfound consensus on China will soon find its limits, no matter who is elected president.

GOP hawks, including Sens. Tom Cotton of Arkansas and Josh Hawley of Missouri, describe China as an adversary in terms reminiscent of the Cold War — “an evil empire,” in Cotton’s words.

They’ll beat up Biden over anything that smacks of engagement.

That makes the new status quo on China something like the Cold War consensus, when Democrats and Republicans agreed that the Soviet Union was a threat but disagreed on how to contain it.

Since the Cold War ended in 1991, strategists have sought a new organizing principle for American foreign policy.

For a few pleasant years in the 1990s, the unifying idea was the “enlargement” of democracy; after Sept. 11, 2001, it was a global war against terrorist groups. Cynics said the United States was in search of a new enemy.

So count this as an unexpected byproduct of the presidential campaign: We have found, if not quite an enemy, a bipartisan adversary in China.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.