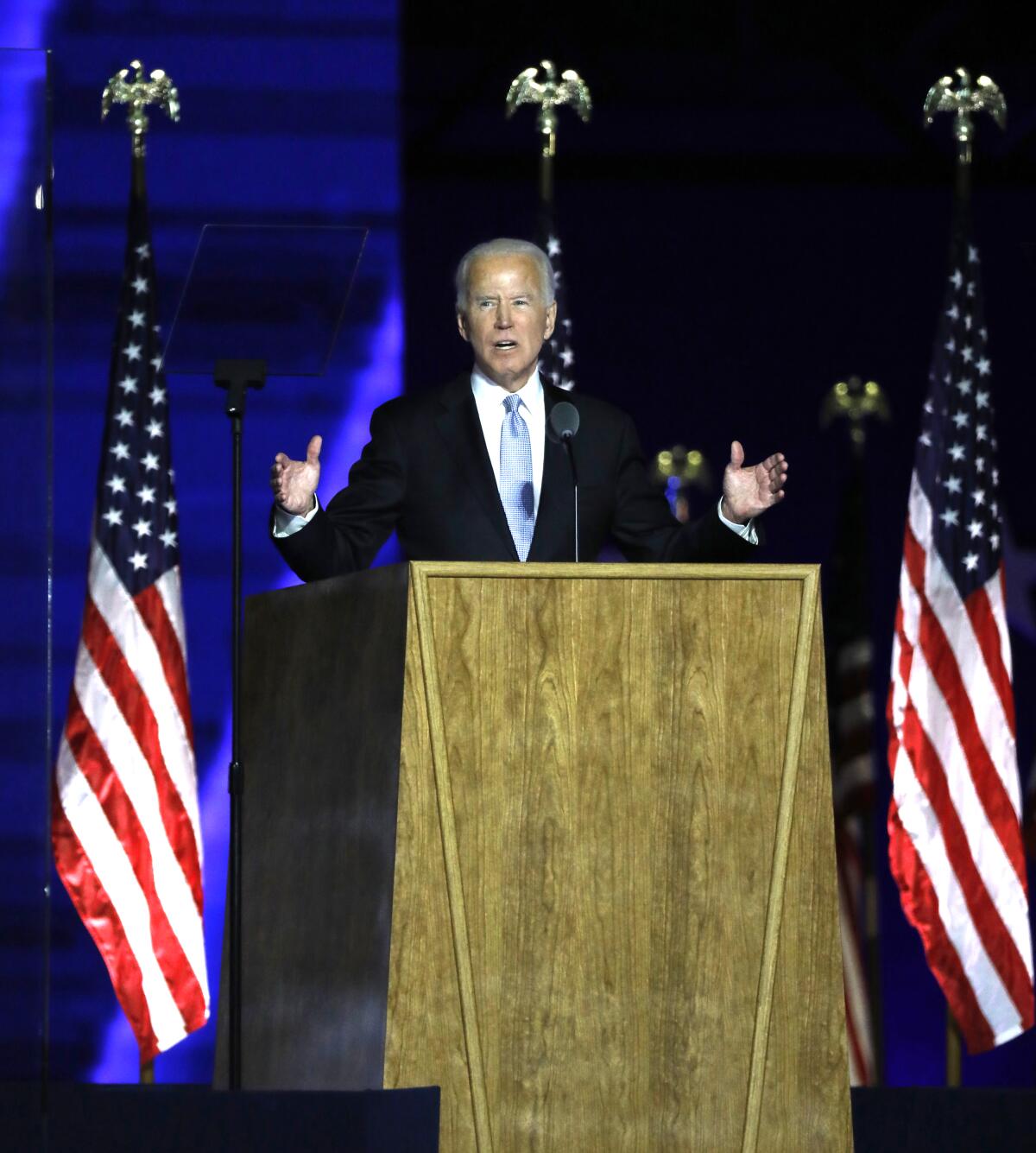

Biden has achieved his No. 1 campaign promise: Beat Trump. Now what?

WASHINGTON — When Joe Biden steps into the Oval Office in January, he will already have fulfilled his No. 1 campaign pledge: to oust President Trump.

That likely will turn out to have been the easy part. It will be much harder for Biden to deliver on his broader promises to push far-reaching progressive initiatives to address the health, economic and social crises besetting the nation.

Senate Republicans are poised to deep-six Biden’s agenda in Congress, whether they keep control or Democrats eke out a one-vote majority. Biden’s party is already roiled by competing demands from anxious centrists and restless progressives. The broad, ideologically diverse coalition that united behind Biden out of disgust for Trump is quickly fracturing.

Joe Biden was elected the 46th president of the United States when Pennsylvania delivered the electoral votes he needed to capture the White House.

“This administration will be dealing with a lot of incoming all at once,” said Vanita Gupta, a former Obama administration official who now runs the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, an influential progressive coalition. Linking arms for an election is one thing, she said. “The governing agenda gets a lot messier.”

Biden’s much-vaunted experience and willingness to work across party lines will be put to an immediate test as he navigates a nation further polarized in the Trump era.

“It will be a challenge, but he is the right person for this moment,” said Amanda Litman, an advisor to Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign.

Joe Biden wins election and calls for national unity as President Trump continues to vow to fight the results.

The campaign season party truce that spared Biden from sniping progressives who wanted a bolder agenda and centrists who worried he was drifting too far left is breaking down amid finger-pointing over disappointing down-ballot results. The sides already are jostling over decisions Biden must make on personnel, strategy and policy as his administration takes shape.

Democrats lost seats in their House majority, an unusual outcome for a party that won the White House. Their high hopes for winning a majority in the Senate have nearly vanished — Democrats’ remaining chance is to win two runoff elections for Senate seats in Georgia on Jan. 5, a long shot.

Still, Biden and his running mate, California Sen. Kamala Harris, are undeterred from moving quickly on an ambitious agenda that they say the perilous times demand.

“They are not getting elected to sit on their hands,” said Jared Bernstein, a progressive economist and longtime Biden advisor who is a top contender to help lead the White House economic team. “When the moment calls for going big, they are comfortable doing so.”

Bernstein pointed to two areas where voter frustration across party lines creates an opportunity for the new administration to move quickly: COVID-19 is still killing more than 800 Americans a day as fresh virus outbreaks multiply across the globe, and the U.S. economy is struggling to recover, with unemployment still twice what it was a year ago. Both problems have spotlighted racial inequities, economic and health-related, that together with incidents of police brutality sent protesters to the streets this year by the millions.

Biden has campaigned on policies designed to address not just current health and economic crises but also the underlying inequities that predated the pandemic. The measures include increasing the minimum wage, political reform and expanding Obamacare and Medicare.

“The urgency is not merely to patch up some of the most immediate wounds, including controlling the virus and providing relief people need,” Bernstein said. “It is creating an economy that is more resilient to the kind of shocks we face these days.”

Yet even as the president-elect channels Franklin D. Roosevelt with big plans and ambitions amid crises, he doesn’t have the voter mandate or the congressional votes to spare that Roosevelt did.

“You can count on the Senate to stand firm against the Democrats’ radical agenda,” Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) said Thursday on conservative Hugh Hewitt’s radio show, referring to proposals like making the District of Columbia a state and expanding the Supreme Court. “I assure you none of that nonsense will even come up for a vote in the United States Senate in the next two years.”

Even when it comes to goals that have more bipartisan potential — like anti-COVID-19 measures and economic recovery aid — Republicans will likely be reluctant to go along. Many already had begun to express “spending fatigue” even with a president of their own party in the White House. Trump’s spending and tax cuts had driven current and projected deficits higher than $1 trillion annually even before the pandemic.

“With a President Biden, I don’t think that spending fatigue is going to go away,” said Antonia Ferrier, a former aide to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.). “The prospects for real bipartisan compromise are not great.”

As Biden looks for a way to work with Republicans, he will be navigating the differences in a Democratic Party already looking past him: Biden has said he would be a transitional leader, and the internal fight for the party’s future has already begun.

President Trump is not conceding the presidential election to Joe Biden and is expected to fire foes and pardon friends.

The first field of battle is the choice of personnel for the administration, and tensions were already running high before election day.

Reports that liberal icons Sen. Bernie Sanders and Sen. Elizabeth Warren were angling for Cabinet posts — Labor and Treasury secretaries, respectively — filled Biden’s Wall Street backers and moderate Democrats with dread. As the Biden transition team vetted Republicans and business leaders for potential Cabinet posts, the left began sounding alarms.

Progressive lawmakers including Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York signed a letter demanding that Biden shun appointees with corporate ties. Sanders sent a list of dozens of progressives he’d recommend for administration posts, including in the Cabinet and among junior staff.

Even as progressive leaders have bristled at talk of recruiting Republicans to the Cabinet, and at Biden’s persistent efforts during the campaign to keep daylight between himself and the left, they see big opportunities in the agenda he has committed to push.

“It is a real path for massive change,” said Larry Cohen, a former president of the Communications Workers of America, who is the board chairman of Our Revolution, the progressive coalition founded by Sanders. “Like my great-grandmother would say: ‘I will watch his feet and not his mouth.’ If his feet do all the things he is saying he will do, I will not be worrying about the things he won’t do.”

Cohen and other progressives are trying to rally Democrats to at least stay united through the Senate runoff elections in Georgia. In an Our Revolution fundraising appeal, Cohen warned that if McConnell keeps control, “he will do everything in his power to make President Biden forget his campaign promises.”

Kamala Harris will be the first female vice president, as well as the first Black and Asian American person to occupy that post.

If faced with a Republican Senate majority, Biden may be tempted to default to a centrist, pragmatic approach more natural to him before he tacked to the left in the Democratic primary and in the face of the pandemic.

If Democrats had control of the House and Senate, the debate would be “between far left and center left about how big to go; that might be harder for him,” said Lanae Erickson, a vice president of Third Way, a centrist Democratic group. But if Republicans run the Senate, “the question is how big will Republicans let him go. It’s no longer an intraparty argument.’’

Some progressives argue that Biden should not use Republicans’ obstacles as an excuse to back away from his agenda, that he should instead reach beyond the Washington Beltway for support.

“Biden is going to have to be willing to do something he hasn’t always been willing or able to do — to work with and engage with and mobilize grassroots energy,” said Rashad Robinson, president of Color of Change, a civil rights group. “That is one of the powerful forces at the back of the Trump presidency. “

That could mean choosing issues like a minimum wage increase or an infrastructure program, then trying to build political pressure in Senate Republicans’ home states.

“Progressive economic ideas are still very popular and would help in bringing working-class people back to the Democratic Party,” said Faiz Shakir, who managed Sanders’ 2020 presidential campaign.

Joe Biden was elected the 46th president of the United States when Pennsylvania delivered the electoral votes he needed to capture the White House.

Democrats have much at stake in Biden’s ability to have a consequential presidency, after an election that mobilized a record numbers of voters. If Congress is uncooperative, Biden will be under heavy pressure to use the tools of presidential power — executive orders, regulatory actions and the bully pulpit — as aggressively as Trump did.

“If Biden does not do all he can to advance a progressive agenda, if Democrats don’t fight with every tool in their arsenal,” said Litman, the former Hillary Clinton aide, “you’re going to have a generation of voters, a cohort of people, who have been activated by this election who — if they don’t feel productive in the next couple of years — we will lose them forever.”

But Biden will also have to keep the support of moderate Democratic senators, including Joe Manchin III of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona. Democrats from purple and even red states see opportunity after so many Republican and independent voters supported Biden, who promised collaboration and to govern from the center.

Biden’s balancing act may provide an opening to progressives who are not the most famous firebrands, think Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez, but instead are behind-the-scenes coalition builders — lawmakers such as Ohio Sen. Sherrod Brown or California Reps. Ro Khanna (D-Fremont) and Karen Bass (D-Los Angeles).

Khanna says he sees a lot to like in Biden’s blueprint for governing, and potential to use it as a springboard for more ambitious plans down the line.

“There will be a honeymoon period where people will want Biden to succeed for the sake of the country,” Khanna said. “Obviously there has to be engagement with progressives and progressive ideas. If it looks like progress is not being made, things could change.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.