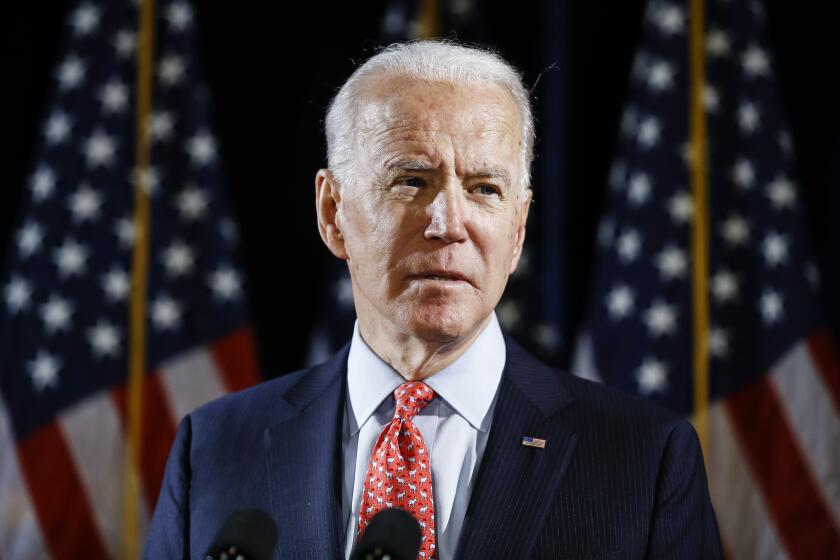

Signing ‘Buy American’ order, Biden pushes for urgent relief

- Share via

BALTIMORE — President Biden signed an executive order Monday to boost government buying from U.S. manufacturers, as talks with Congress over a $1.9-trillion stimulus package that he considers essential to the nation’s recovery showed few signs of progress.

The executive order is among a flurry of moves by Biden during his first full week to publicly show he’s taking swift action to heal an ailing economy. Biden reiterated Monday that he believes the country is in a precarious spot and and that relief is urgently needed, even as he dismissed the possibility of embracing a scaled-down bill to secure passage faster. Among the features of the stimulus plan are a national vaccination program, aid to reopen schools, direct payments of $1,400 to individuals and financial relief for state and local governments.

“Time is of the essence,” Biden said. “I am reluctant to cherry-pick and take out one or two items here.”

Biden, meanwhile, was growing more bullish on vaccine distribution in the U.S., after he and his aides faced criticism for their caution in setting vaccination targets for the virus-weary nation. Biden told reporters that he believes 150 million shots in arms may be achievable in his first 100 days in office — up from 100 million doses — and that he expects widespread availability of the vaccines for Americans by spring, with the U.S. “well on our way to herd immunity” by summer.

Biden’s comments come after his team held a call Sunday to outline the stimulus plan with at least a dozen senators, while the president has also privately talked with lawmakers.

“There’s an urgency to moving it forward, and he certainly believes there has to be progress in the next couple of weeks,” White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said Monday. She warned that action needed to be taken before the U.S. reaches an “unemployment cliff” in March, when long-term unemployment benefits expire for millions of Americans.

Just as President Trump moved quickly to turn back Obama-era policies, Joe Biden will do the same to Trump actions soon after taking office as president Wednesday.

But Republicans on Capitol Hill were not joining in the push for immediate action.

One key Republican, Sen. Susan Collins of Maine, said after Sunday’s call that “it seems premature to be considering a package of this size and scope.” Collins described the additional funding for vaccinations as useful while cautioning that any economic aid should be more targeted.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said Monday that “any further action should be smart and targeted, not just an imprecise deluge of borrowed money that would direct huge sums toward those who don’t need it.”

Biden sought to downplay the rhetoric from GOP lawmakers, saying, “I have been doing legislative negotiations for a large part of my life. I know how the system works.”

“This is just the process beginning,” he added. “No one wants to give up on their position until there’s no other alternative.”

Monday’s order will likely take 45 days or longer to make its way through the federal bureaucracy, during which time wrangling with Congress could produce a new aid package. That would be a follow-up to the roughly $4 trillion previously approved to tackle the economic and medical fallout from the coronavirus.

The order was aimed at increasing factory jobs, which have slumped by 540,000 since the pandemic began last year.

“America can’t sit on the sidelines in the race for the future,” Biden said before signing the order in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building. “We’re ready, despite all we’re facing.”

President Biden is putting forth a national COVID-19 strategy to ramp up vaccinations and tests, reopen schools and businesses, and increase mask use.

Biden’s order would modify the rules for the Buy American program, making it harder for contractors to qualify for a waiver and sell foreign-made goods to federal agencies. It also changes rules so that more of a manufactured good’s components must originate from U.S. factories. U.S.-made goods would also be protected by an increase in the government’s threshold and price preferences, the difference in price over which the government can buy a foreign product.

It’s an order that channels Biden’s own blue-collar persona and his promise to use the government’s market power to support its industrial base, an initiative that former President Trump also attempted with executive actions and import taxes.

“Thanks to past presidents granting a trade-pact waiver to Buy American, today billions in U.S. tax dollars leak offshore every year because the goods and companies from 60 other countries are treated like they are American for government procurement purposes,” said Lori Wallach, director of Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch and a critic of past trade agreements.

While Trump also issued a series of executive actions and tariffs with the goal of boosting manufacturing, he didn’t attempt to rewrite the guidance for what constitutes a U.S.-made component or tighten the process for granting exemptions to buy foreign goods, a key difference from Biden’s agenda, Biden’s administration said.

The order also has elements that apply to the separate Buy America program that applies to highways and bridges. It aims to open up government procurement contracts to new companies by scouting potential contractors. The order would create a public website for companies that received waivers to sell foreign goods to the government, so that U.S. manufacturers can have more information and be in a more competitive position.

Past presidents have promised to revitalize manufacturing as a source of job growth and achieved mixed results. The government helped save the automotive sector after the 2008 financial crisis, but the number of factory jobs has been steadily shrinking over the course of four decades.

The number of U.S. manufacturing jobs peaked in 1979 at 19.5 million and now totals 12.3 million, according to the Labor Department.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.