Mar-a-Lago primary: Trump wields power with endorsements, but some in GOP fear midterm damage

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Former President Trump, again upending American political norms, is moving to remake Congress and the Republican Party in his own image.

Since leaving the White House, he has issued a spate of endorsements of House and Senate candidates for next year’s crucial midterm election, including an array of political outsiders, conspiracy theorists and others who — like Trump himself — break the traditional mold.

While most former presidents have steered clear of politics, Trump is intervening in Republican primaries like an old-style ward boss: rewarding allies, punishing enemies and trying to use his vast popularity among Republican voters to keep himself and his agenda at the center of the GOP.

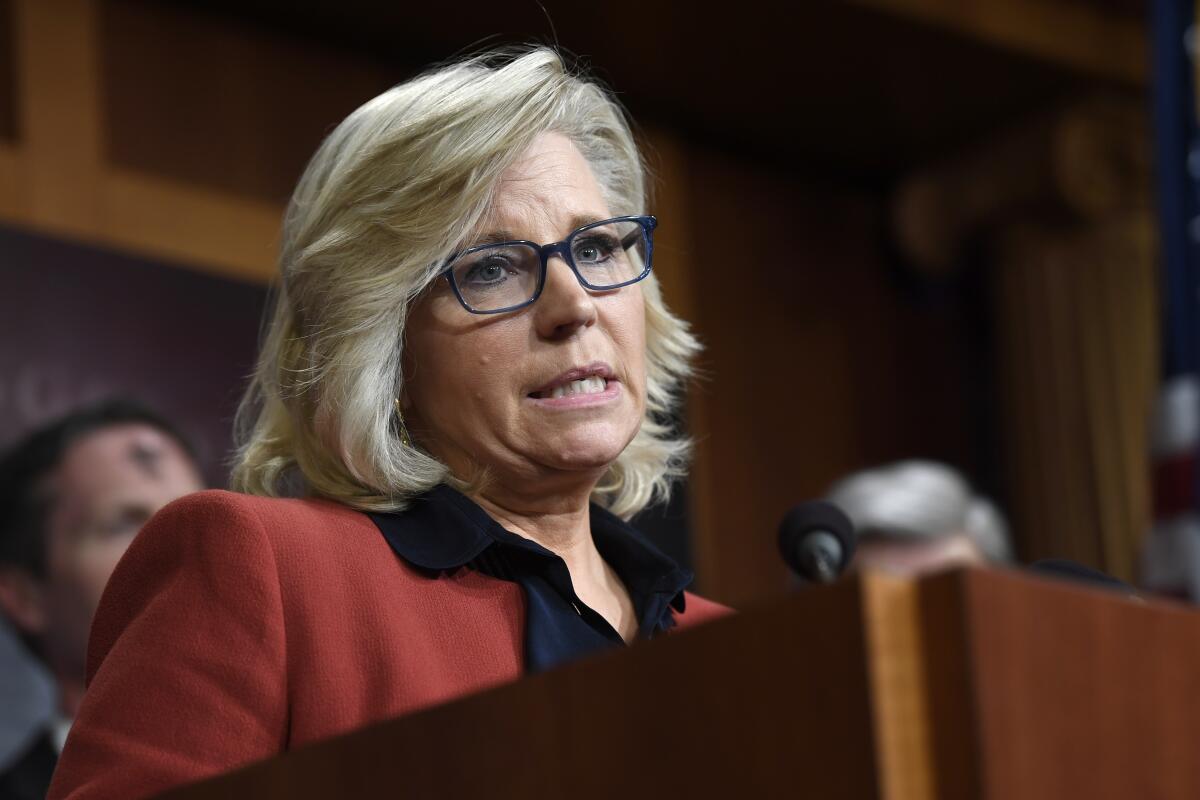

Targeting one of his most prominent Republican critics, Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming, Trump plans to meet this week at his New Jersey golf club with Wyoming Republicans who are running against her. His goal: to endorse one, clear the field of others and set up a head-to-head contest.

Republicans face a midterm dilemma: Trump has an iron grip on the party, but he risks alienating swing voters.

But Trump’s heavy hand in GOP primaries carries risks for his party. Some Republicans fear that some of his endorsements — those based not on electability but on candidates’ loyalty to him and his false claim that the 2020 election was stolen — could make it harder for the party to win in swing states.

“If we as Republicans continue to relitigate a past lost election, we will not position ourselves to win in the midterms,” said John Watson, former Georgia Republican Party chairman. “We have the issues on our side if we will just get out of our own way.”

A former NFL star Trump is promoting for a potential Senate run in Georgia — Herschel Walker — is beloved in the state where he started his career as a Heisman Trophy winner. But he is an untested political novice, and it’s been decades since he lived in Georgia.

In North Carolina, Trump is backing Rep. Ted Budd to replace the state’s retiring Republican senator. Budd, a gun store owner, is an ardent defender of the former president but has trailed in early polling and fundraising.

In Arizona, many Republicans believe Gov. Doug Ducey would be the best candidate against Democratic Sen. Mark Kelly. But Ducey, who has been pummeled by Trump for not doing more to overturn Biden’s 2020 victory in the state, has said he won’t run.

Trump derided him on Ducey’s own turf Saturday, recalling in a Phoenix speech his reaction to Ducey’s possible candidacy. Trump said he was asked, “Sir, would you like him to run for the Senate?” and replied, “He’s not getting my endorsement, I can tell you.”

Trump allies argue that the party would face far graver political problems if he were not so engaged. Many see him as essential to motivating GOP voters in 2022’s high-stakes election, especially since turnout usually drops in midterms.

“This is largely going to be a turnout-based election. If the candidate is Trumpy, that’s not necessarily a bad thing,” said a person familiar with the former president’s thinking. “The wishy-washy vanilla candidate is going to be problematic in a race that is really all about energy and turnout and excitement.”

The aggressive endorsement strategy also is a gamble for Trump himself: If his candidates lose, he may end up looking like a paper tiger.

Conflicted Republicans weigh life after Trump following seven GOP senators’ vote for conviction in the Senate impeachment trial.

Trump is trying to do something that no president — let alone a defeated former president — has tried on such an ambitious scale. The closest parallel is President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who in 1938 tried, mostly unsuccessfully, during Senate primaries to encourage the defeat of conservative Democrats opposed to his New Deal.

“There is no clear parallel to Trump’s effort to take over the GOP,” said John J. Pitney Jr., a political scientist at Claremont McKenna College.

Political bosses at the state and local level once wielded great power over party nominations, he noted, but stuck to their own turf. “Chicago’s Mayor Daley did not try to influence Democratic politics in Los Angeles,” Pitney said.

The National Republican Senatorial Committee, a party campaign arm, has pledged to stay out of contested open primaries in 2022. The committee’s chair, Sen. Rick Scott of Florida, tried without success to get Trump to stay neutral until after GOP primary voters pick the nominees.

Trump instead has been conducting what some Republicans call the Mar-a-Lago primary. He has met, mostly at his Florida resort, with dozens of GOP candidates seeking his support. Those meetings are often a crucial part of his decision on whether to endorse.

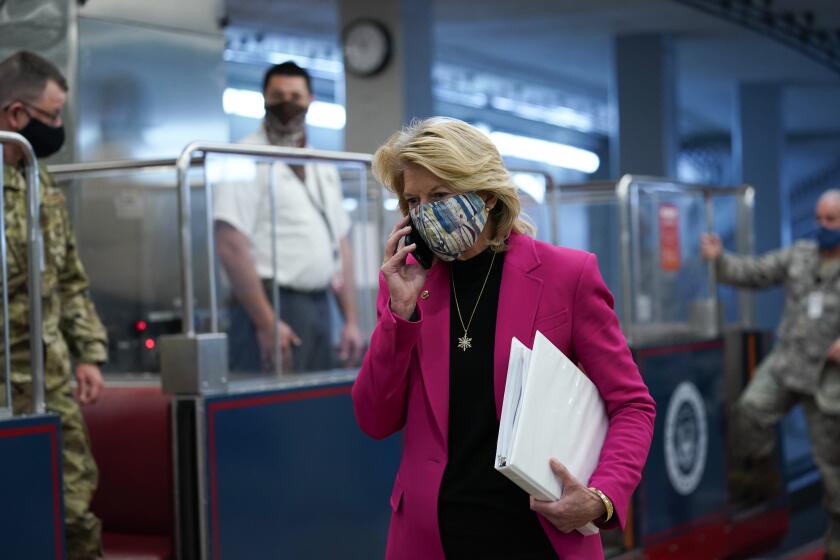

It was a few days after such a visit that Trump announced he was endorsing Kelly Tshibaka, a former Alaska government official running against GOP Sen. Lisa Murkowski. Three-term incumbent Murkowski is a top Trump target because she opposed him and many of his priorities from the outset of his presidency. Trump won Alaska by double-digit margins in 2016 and 2020.

“Her support among Republicans has cratered,” Tim Murtaugh, a former Trump campaign advisor who is now advising Tshibaka, said of Murkowski. “It’s hard to see how she puts her coalition together without any Republicans.”

Murkowski has not formally announced her bid for reelection but has reported strong fundraising. Her supporters believe she will benefit from a new Alaska voting system that eliminates partisan primaries and introduces ranked-choice voting.

And in a recent focus group of Alaska Trump supporters, some Murkowski critics still gave her credit for channeling federal aid to the state.

“There’s a ‘Murkowski delivers for Alaska’ campaign in there,” said Sarah Longwell, a Republican Trump critic who conducted the focus group.

There is little risk that Democrats will win Alaska, but Trump’s endorsement puts him at odds with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky and the Republican Senatorial Committee, who have backed Murkowski.

In deep-red Alabama, Republicans are all but guaranteed to hold on to the seat of retiring GOP Sen. Richard C. Shelby, but a bitter primary is brewing. Trump has endorsed Rep. Mo Brooks, a vocal supporter of election-fraud claims who has asserted that anti-COVID masks could cause cancer.

Trump and Brooks are in an escalating feud with a primary rival endorsed by Shelby — his former chief of staff, Katie Britt. In a statement this month, Trump derided Britt and called Shelby a “RINO” — Republican in name only — and an ally of “Old Crow Mitch McConnell.”

Arizona is far more politically competitive, and beating Kelly, the new Democratic senator, is a top GOP goal for 2022. Many Republicans hoped Ducey would run after easily winning two terms as governor, but in January he said he would not.

Yet Scott, the Republican Senatorial Committee chair, said on the podcast “Ruthless” last week that there still was “a shot” that Ducey would get into the race.

The power and limits of Trump’s backing were illustrated in North Carolina early last month when he made his surprise endorsement of Budd in the contest to succeed retiring GOP Sen. Richard M. Burr. That catapulted Budd from the back of the pack to new prominence.

But it did not clear the field. Former Gov. Pat McCrory is leading most polls and raised nearly $1.25 million in the second quarter of 2021, compared with Budd’s $700,000, which included almost a month of post-endorsement fundraising.

Paul Shumaker, a GOP pollster who advises McCrory, raised doubts in a memo to his clients about the value of a Trump endorsement. His polling found that North Carolina voters were more likely — by a 10-percentage point margin — to support a Biden-endorsed candidate than one backed by Trump.

Perhaps no potential Senate candidate has gotten as much encouragement from Trump as Walker, in one of the most important races of 2022 — the fight to unseat Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock of Georgia. Like Kelly in Arizona, Warnock is considered especially vulnerable because he will face voters after only two years in office. Both were elected for the first time in the most recent election cycle to partial Senate terms.

Walker’s promoters say that if he runs, he would be unbeatable in a GOP primary and a strong general election candidate because he is legendary in Georgia for his years as a star University of Georgia running back. Having a well-known Black candidate run against Warnock, who is also Black, would be an added political plus for the GOP.

Many potential Republican candidates have stayed on the sidelines, waiting to see whether Walker will run, as Warnock has continued to build his campaign war chest. GOP officials say they are confident Walker will run, but expect he may wait until the fall to announce.

“Given the lead he continues to enjoy in the polls and among Georgians, there appears to be no rush to jump into the fray,” said Randy Evans, an influential Republican lawyer in Georgia who was Trump’s ambassador to Luxembourg.

But others are worried that Walker may not be the dream candidate because he is so untested and will have to contend with questions about his mental health and reports of threatening behavior before he was treated for dissociative identity disorder — a topic he addressed in a 2008 book.

“Being a favorite football player is materially different than being in the white-hot heat of a U.S. Senate campaign,” said Watson, the former Georgia GOP chair. “If it launches, it will go high in the air to start; I don’t know where it lands. I have real trepidation.”

So far, Trump has stayed out of the GOP primary in Ohio. But the field of candidates to succeed retiring GOP Sen. Rob Portman is crowded with Trump loyalists, so there is less incentive for him to endorse.

“It’s important to watch these candidates duke things out,” said the person familiar with Trump’s thinking. “He’s generally sitting back now and watching fields take hold.”

Trump is not sitting back on the Wyoming GOP primary. The incumbent, Cheney, became Trump Enemy No. 1 after she condemned him for lying about the 2020 election and for the Jan. 6 siege of the Capitol by his supporters.

A large and growing field of Republican candidates has emerged in Wyoming, but none with a dominating claim to the nomination. Trump and other Cheney critics worry that a splintered field gives her a clear shot at winning the nomination and reelection, and are looking for a way to winnow the field.

Pro-Trump Wyoming Republican donors and party activists have been meeting to interview and vet the announced candidates. Just last week they identified two — Charles Gray, a member of the Wyoming Legislature, and Darin Smith, an attorney and businessman — as the best pro-Trump candidates.

Jeff Wallack, a Trump loyalist involved in the vetting group, says that more candidates may enter the field soon, and that he hopes Trump will wait to review them all before making his endorsement.

“Trump’s endorsement is absolutely critical,” Wallack said. “When he endorses, everybody else should drop out.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.