Column: Are Californians chumps to play fair on congressional redistricting?

In 2010, a year of deep political discontent, Californians voted to strip lawmakers of their power to draw the state’s congressional boundaries.

It wasn’t close. Despite fierce opposition from leading Democrats, among them House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of San Francisco, and resistance from potent interest groups such as the California Teachers Assn., Proposition 20 passed by a walloping 61% to 39%.

The purpose was to introduce competition into elections that had long been a slam-dunk for one party or the other by handing the map-making responsibility over to a 14-member commission made up of regular folks — which is to say those not holding office or otherwise self-interested.

And it’s worked.

After years of precooked contests — including a decade in which just one congressional seat flipped parties — California has become a hub of political competition. As many as 10 of the state’s 52 House seats could go either way in next year’s midterm election. That’s by far the most of any state.

Unlike gerrymandered states, California may host as many as 10 competitive races

Some Democrats see that as a problem. The state’s overwhelming majority party has been handcuffed by the commission, they say. The citizens panel, seated after an exhaustive screening process, is split evenly between Democrats and Republicans, with a handful of members claiming loyalty to no political party.

(Requisite background: Every decade, the state’s political boundaries are redrawn to account for population shifts over the previous 10 years. The panel is drawing 176 maps — for Congress, the 120-seat Legislature and four members of the Board of Equalization, which oversees tax collection. The deadline for completion is Dec. 27.)

The Democratic argument goes something like this: Californians may feel all warm and fuzzy for doing the virtuous thing — attempting to divorce politics from redistricting to the greatest extent possible — but other states with far less saintly Republicans are doing everything possible to maximize GOP gains.

(It should be pointed out that in states where Democrats have the power — Illinois, Maryland and New Mexico among them — they have done their best to boost their party at the expense of the GOP.)

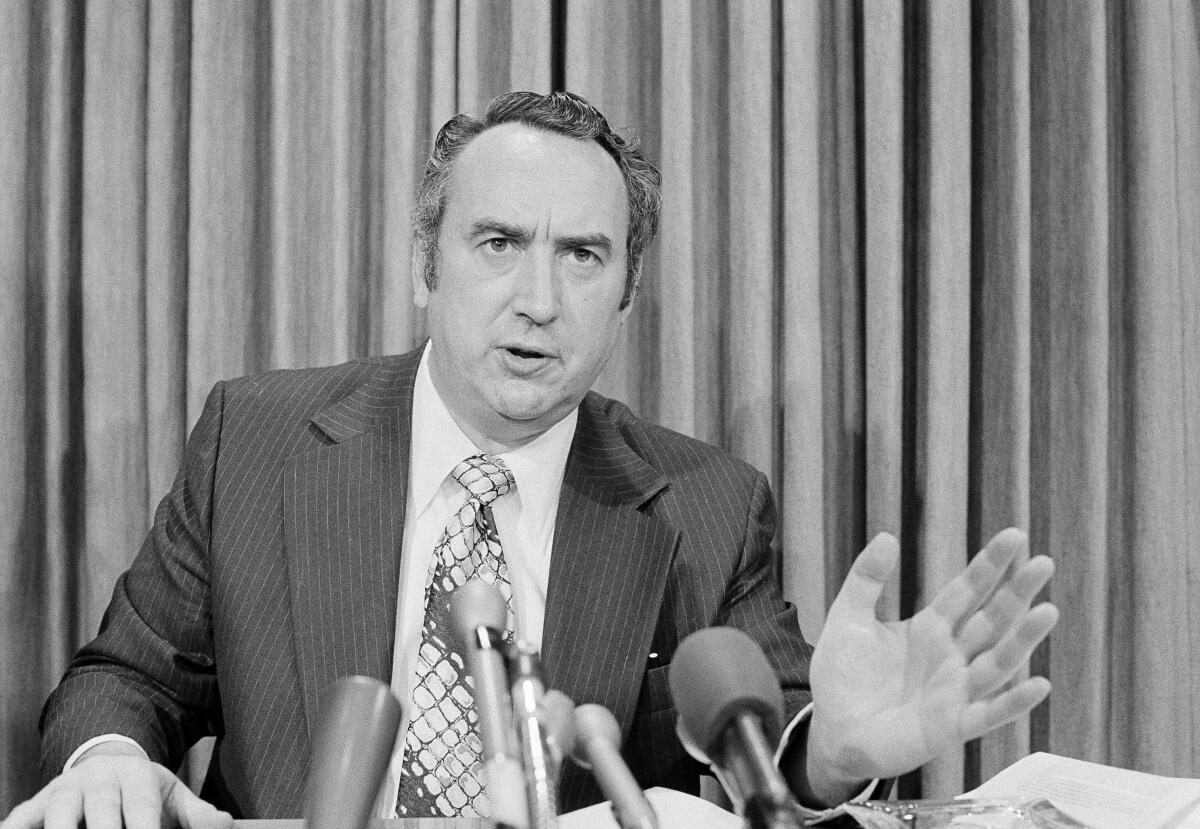

“When you have a system that says we’re going to have purity in California and skulduggery in Texas, you end up with an unrepresentative [House] chamber,” Rep. Brad Sherman of Los Angeles griped to the New York Times. “We want to live in a system where neither party gets screwed. But worst of all is a system where only one party gets screwed.”

David Wasserman, one of the country’s leading nonpartisan congressional analysts, estimated that neutral commission maps in the Democratic-leaning states of Colorado, New Jersey, Virginia, Washington and California will end up costing the party 10 to 15 seats they could have commandeered through partisan gerrymandering.

Had the late San Francisco Rep. Phillip Burton, the Picasso of partisan map-drawing, been alive and controlling the process, Wasserman calculates, Democrats could have picked up six to seven House seats just in California.

Republicans need a gain of five seats nationwide to win control of the House. Given history — the party in the White House almost always loses seats in the midterm election — and President Biden’s sagging approval rating, that’s likely to happen well before the sun sets over the Pacific on Nov. 8, 2022.

The consequences, as Sacramento Democratic strategist Steve Maviglio says, could be profound, especially if Republicans also seize control of the Senate.

“On the national scale that will result in a Congress that will peel back everything Democrats have accomplished in the last year and adopt anti-climate, anti-choice, pro-gun policies, and other positions Democrats abhor,” Maviglio said in an email exchange.

He notes that legislation that would bar gerrymandering nationwide — part of an expansive bill aimed at protecting voting rights — has passed the Democratic-run House but stalled due to Republican opposition in the Senate.

“Democrats are playing fair,” Maviglio said. “Republicans aren’t.” So why, he asked, should Democrats unilaterally disarm themselves?

Harris is just the latest vice president to learn the job is ripe for ridicule.

There is an awful lot to dislike about the way redistricting is done. It has grossly distorted our national politics and given way too much power to lawmakers whose views reflect a minority of the electorate.

But the Supreme Court has ruled that partisan gerrymandering is OK, or, more specifically, that it’s not up to the federal courts to step in and change the line-drawing process.

Given that, until and unless Congress acts to change the rules, the question is whether California should go back to the old way of doing things, which allowed politicians to choose their voters, rather than the other way around. That naked self-dealing is one reason Californians took politicians’ map-making power away.

“I just feel like at some point we have to say, ‘Stop,’” said Paul Mitchell, a political demographer in Sacramento and a consultant working on redistricting throughout the country.

“You can’t fight gerrymandering with gerrymandering,” he went on. “It’s just going to create a further downward spiral of people feeling like elections are rigged, that politicians are running the show and that our representatives aren’t truly representing the people — they’re representing the people they want to put in their districts.”

It’s easy to find fault with California’s commission and those doing its work, as with any endeavor touched by human hands. But at least the work is being done in plain sight. Commissioners have held more than 80 hearings and logged nearly 30,000 public comments.

Feel free to criticize. But be mindful that the reason people can offer criticism — and push for remediation — is because the commission is not acting in secret and presenting the public with a finished product, like it or not.

That’s how it used to be done, and a substantial number of people didn’t like it.

The voters have spoken. They get the last word.

More to Read

Get the latest from Mark Z. Barabak

Focusing on politics out West, from the Golden Gate to the U.S. Capitol.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.