Column: A small-city mayor takes on big oil and political propaganda

- Share via

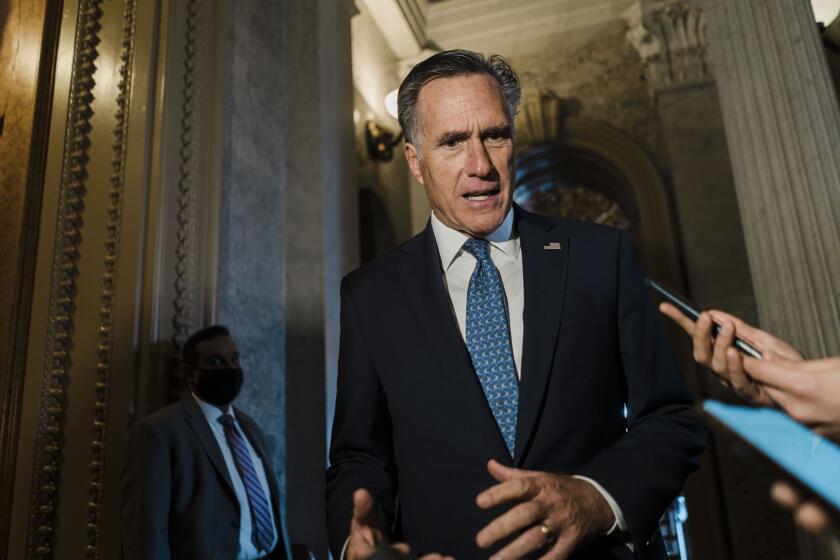

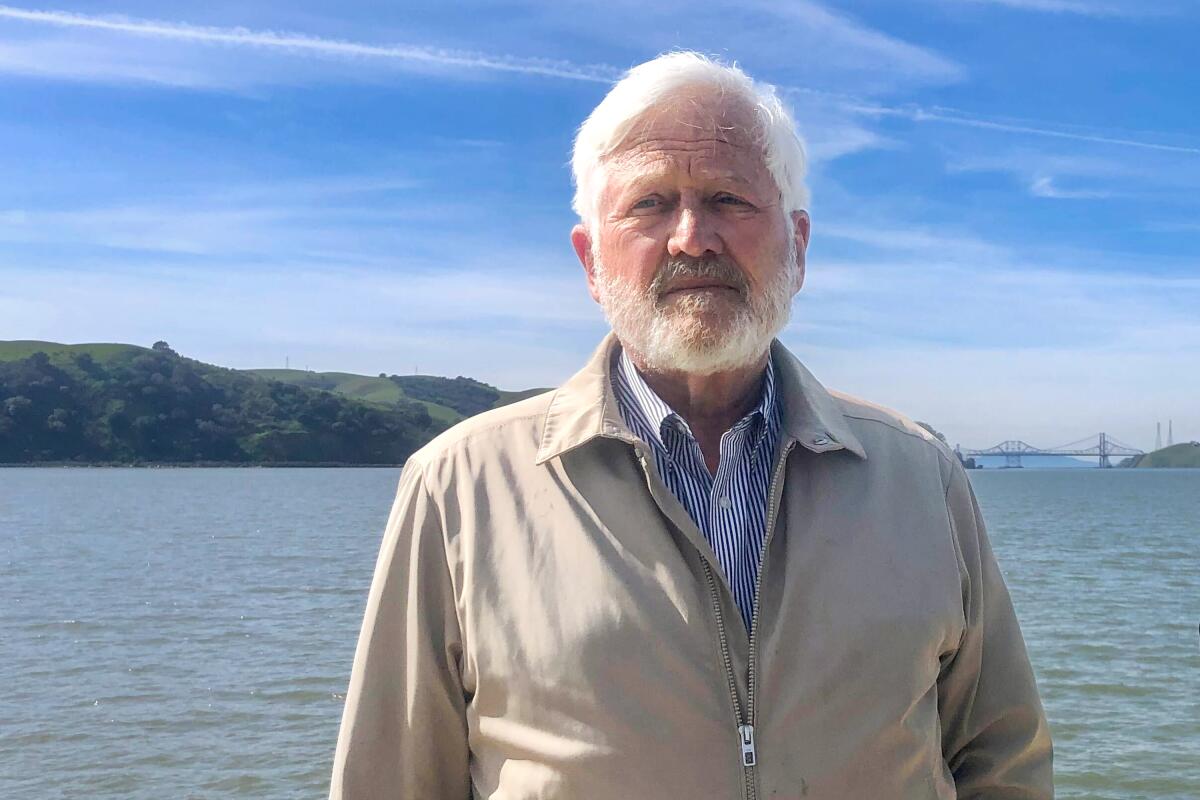

BENICIA, Calif. — Steve Young could have enjoyed a nice, quiet retirement in this charming waterfront community in the northern part of the Bay Area.

But Young is a sociable type and was eager to make new acquaintances after he and his wife moved here in 2012. He’s not the kind to hang out in bars, the 70-year-old Young said, and he doesn’t play any competitive sports. So one way to meet folks, he figured, was to serve on a local board or commission.

After several interviews, Young landed a spot on Benicia’s Planning Commission; it helped that he had spent his career in local government, retiring as a leader of Sacramento’s Housing and Redevelopment Agency. His appointment to the commission led to his election to the City Council, which in turn positioned Young for a successful 2020 run for mayor — and a fight with the oil company that looms large in this small city.

With the vice president a little-known quantity, her fortunes are tied to President Biden’s. Her miscues also aren’t helping.

Young’s victory, and the deep-pocketed campaign against him, has placed him at the intersection of two of the more insidious trends in politics today: the flood of limitless money and the gutting of local news media, which has left a void too easily filled by propaganda and misinformation.

“I understand that it’s legal,” Young said of the incredible amounts of cash sloshing around campaigns from the White House to City Hall. “I understand the Supreme Court said it’s OK. But it’s not right. And in my view it’s not democratic.”

So Young is pushing back as best he can, recruiting independent campaign fact-checkers and seeking a municipal ordinance to prevent digital manipulation of political ads and other willful deceit.

“People can say whatever they want,” Young said, “and if you don’t have the money to refute it, it will stick with voters.”

Benicia, which is one of California’s oldest cities, is home to about 28,000 residents, a thriving artists colony and a sprawling oil refinery owned by Valero Energy Corp. The San Antonio-based firm is the city’s largest employer and taxpayer, a major political force and a source of considerable local controversy.

The two worst refinery accidents in the Bay Area in recent years occurred in Benicia. Last month, San Francisco public radio station KQED reported the plant had released excessive levels of hazardous chemicals for more than 15 years before regulators discovered the emissions.

Naturally, where there’s smoke, there’s an attempt to gain political influence.

In the last two elections, Valero spent hundreds of thousands of dollars supporting its preferred candidates for mayor and City Council, and targeting those, like Young, who favored tighter regulation of its refinery. (The name of Valero’s political action committee, Working Families for a Strong Benicia, is obviously more palatable than Big Oil Company Spending Huge Sums to Keep Small Community Under Its Thumb.)

Major corporations certainly have a right to weigh in on matters affecting their businesses, their employees and the communities where they operate. According to the Supreme Court, that constitutes political speech protected by the 1st Amendment. Corporations are entitled to as much speech as they care to purchase, which is considerably more than your typical voter or candidate for local office can possibly afford.

“Corporations can essentially buy elected officials ... by pumping money into getting their preferred candidates into office,” or by opposing those “not as beholden or sympathetic,” said Sean McMorris of California Common Cause, a nonprofit good-government organization.

In Benicia, the high-priced campaign against Young by Valero and its allies included mailers that darkened his complexion — presumably to make him appear more sinister — and distorted his voting record and performance on the City Council. Several assertions, Young said, were patently false.

He won nevertheless.

As we took a driving tour of the city — beneath a cloud of blossoming Bradford pears, past white picket fences and Craftsman homes, through the industrial park that houses Valero — Young spoke of the pleasures, and frustrations, of serving as mayor. The job pays $525 a month and comes with healthcare benefits. That’s not a lot given the constant demands, plus added tension over masks and vaccinations, but it’s rooted Young in the community and, as he once hoped, introduced him to lots of people.

“I like it,” he said of his position, after brief consideration.

What he can’t abide is the outsized political influence of the city’s corporate Goliath. Elections in a place like Benicia should be determined, Young said, by candidates knocking on doors and meeting voters, not by whoever wields the heftiest wallet.

So along with Vice Mayor Tom Campbell, Young came up with two proposals to govern campaigns and try to stem Valero’s influence.

The first sought to establish a kind of municipal truth commission. But the city attorney noted the high legal bar facing lawmakers if they sought to enter the campaign fact-checking business.

Young then approached the local newspaper, the Benicia Herald, in hope its meager staff will begin truth-squadding political ads. If the paper is willing, candidates “could use that in some future mailing or social media post, saying a third party has looked at this and it’s false.”

The second proposal, to prevent digital manipulation — like casting a candidate in shadow — and other forms of electronic fakery, is set to go before the city’s Open Government Commission for consideration.

“I want to have something in front of the council by summertime,” Young said as the sun glinted off the Carquinez Strait, “because obviously this has to be in place before people start voting.”

A former advisor to Utah’s buttoned-down senator calls it “Romney unplugged.”

At a time when democracy is under assault, the decimation of local media — often a community’s only source of professionally gathered news — has become more worrisome than ever. Without someone keeping a watchful eye and holding the powerful to account, those with the money and means to have their way will only grow more influential.

Young’s effort is one small step in one small city. But it’s something, and a worthy example others might choose to follow.

One in an occasional series on proposals to fix our politics and strengthen democracy.

More to Read

Get the latest from Mark Z. Barabak

Focusing on politics out West, from the Golden Gate to the U.S. Capitol.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.