A year after outbreak, Africa waits for its share of mpox vaccines

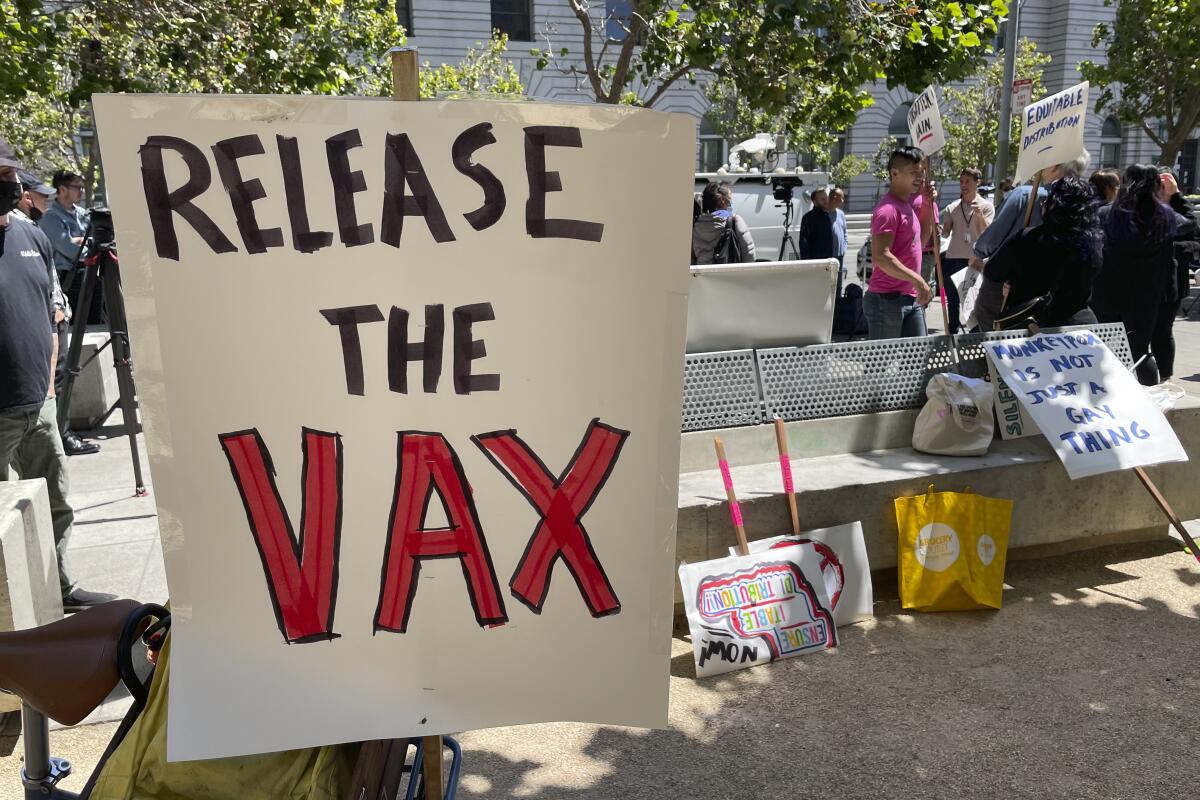

WASHINGTON — As U.S. public health officials brace for a possible resurgence of mpox ahead of the summer festival season, experts are warning that European and North American governments aren’t doing nearly enough to ensure that hard-hit African countries can also beat back the virus.

A vaccine for mpox already existed prior to the U.S. outbreak last year. Thanks in part to that vaccine, which is about 86% effective after two doses, mpox cases have drastically fallen in the U.S. from a peak of 600 new cases nationwide on Aug. 1, 2022, alone to an average of one new case per week in April, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But in lower-income countries such as those African countries where mpox (the virus formerly known as monkeypox) is endemic, health officials still do not have access to the vaccine. That could lead to the virus’ reemergence as a global threat.

The current global mpox outbreak was “a consequence of inaction when it came to the outbreak in Africa,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and an infectious disease physician who has treated patients with mpox. “The strategy of containing monkeypox has to be to vaccinate the at-risk population in Western countries as well as vaccinate at the source to stop the spillover from animal species into humans. You have to do both.”

But the Western world appears set to repeat the same mistakes that led to the current outbreak.

After the mpox outbreak began last spring, wealthy countries rushed to the only maker of the Jynneos smallpox vaccine, Denmark’s Bavarian Nordic, to secure millions of doses.

The same day that Boston recorded the first case of mpox in the U.S., Bavarian Nordic announced the first of a series of contracts with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The $300-million deal would provide the U.S. with 13 million doses. As of late May, the U.S. had administered 1.2 million doses, fully vaccinating approximately 23% of the at-risk population, according to CDC data.

The European Union, Canada, and other countries that Bavarian Nordic did not disclose in company news announcements also bought vaccines from the Danish biotechnology firm. The multimillion-dollar contracts allowed the world’s richest countries to get to the front of the queue for mpox vaccines to protect their citizens from the current outbreak and also to stockpile for the future. Just as they had with the COVID-19 vaccines, rich countries ordered nearly all available and future vaccine doses, leaving poorer countries without the means to protect their health workers and the elderly.

In May, as the World Health Organization announced the mpox outbreak was no longer a public health emergency of international concern, it also warned about “persisting knowledge gaps related to mpox in Africa, the lack of access to vaccines, medicines, and diagnostic testing capacities in many low-income countries.”

On the ground in Africa, senior health officials are worried. “This is a classical example of constrained access for Africa for a product, in this case, vaccines,” said Dr. Ahmed Ogwell Ouma, acting director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, which is based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. “Even if we wanted to buy, there is nowhere to buy because they are manufactured in modest numbers and then countries stockpile them in case they need them, while where it is actually needed, on the continent of Africa, we don’t have access.”

The continent’s health officials have battled with smaller outbreaks for decades without vaccine access. Africa has so far recorded about 1,600 mpox cases and 18 deaths, according to data reported to the WHO. The true numbers could be higher because of limited testing and reporting resources.

Experts say the current outbreak could have been prevented from crossing multiple borders if the virus had been suppressed at its source. According to data from the U.S. CDC, 104 countries which had previously never recorded a case of mpox have now detected the virus in the past year.

Ouma believes that if African countries had received vaccine support, the world would have been spared the outbreak. “The outbreak last year that went global would not have happened if there was access to mpox vaccines on the continent of Africa, because then we will have been able to control the outbreak at source.”

Biden administration officials acknowledge that without suppression of the virus abroad, the U.S. will remain vulnerable at home. “Everyone is aware that even if we were to do a really great job vaccinating domestically, as long as there is mpox that is transmitted in this way across the world, we are always at risk for an outbreak and introduction,” Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, deputy coordinator for the national mpox response at the White House, told The Times.

Even before the current outbreak, the United States had been amassing millions of mpox vaccines for years. Fearing bioterrorism in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, the U.S. invested heavily in Bavarian Nordic and stockpiled over 20 million doses of the Jynneos vaccine. This is in addition to over 100 million doses of another vaccine, ACAM2000, which, although effective, can potentially be fatal for a small group of patients and is therefore not preferred by doctors.

U.S. officials allowed 20 million doses of the Jynneos vaccine to expire and disposed of without sharing them with other countries. When the outbreak began, the country had only 2,400 doses in its stockpile.

So far, only South Korea has pledged to donate 50,000 doses of the vaccine to the Africa CDC for distribution to countries, but those vaccines have yet to be delivered. Ouma said discussions with the United States and the European Union are still ongoing. “There are some regulatory issues that are being worked through,” Daskalakis told The Times.

Experts including Adalja at Johns Hopkins point to Ebola, another viral outbreak, as an model of how international cooperation on global health security has ensured that a deadly virus has been suppressed in its endemic regions and not crossed borders. “When there’s an Ebola outbreak in Africa, there’s an aggressive response to quench it, to offer assistance, to use vaccines, experimental therapies, in order to keep it at bay,” he said.

Since the devastating 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak that killed 11,300 people, governments, pharmaceutical companies and global health bodies have worked together to fight the disease, and have developed a treatment and two vaccines for the strain of Ebola that wrecked West Africa. The vaccines have proven to be highly effective and have been deployed locally during subsequent outbreaks where that strain is spreading to suppress it locally.

In the meantime, African governments are trying to take matters into their own hands to make the vaccines they need at home. In April, a pharmaceutical company in Ghana began construction for a facility that would manufacture malaria, HPV and pneumonia vaccines to be shared with neighboring countries. The Africa CDC is also leading a continent-wide initiative to manufacture key vaccines.

“By doing that, then we will have improved access to these vaccines,” Ouma said. “Otherwise, what is happening now is not ideal, it is not good, it is not viable. It is not safe for the whole world.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.