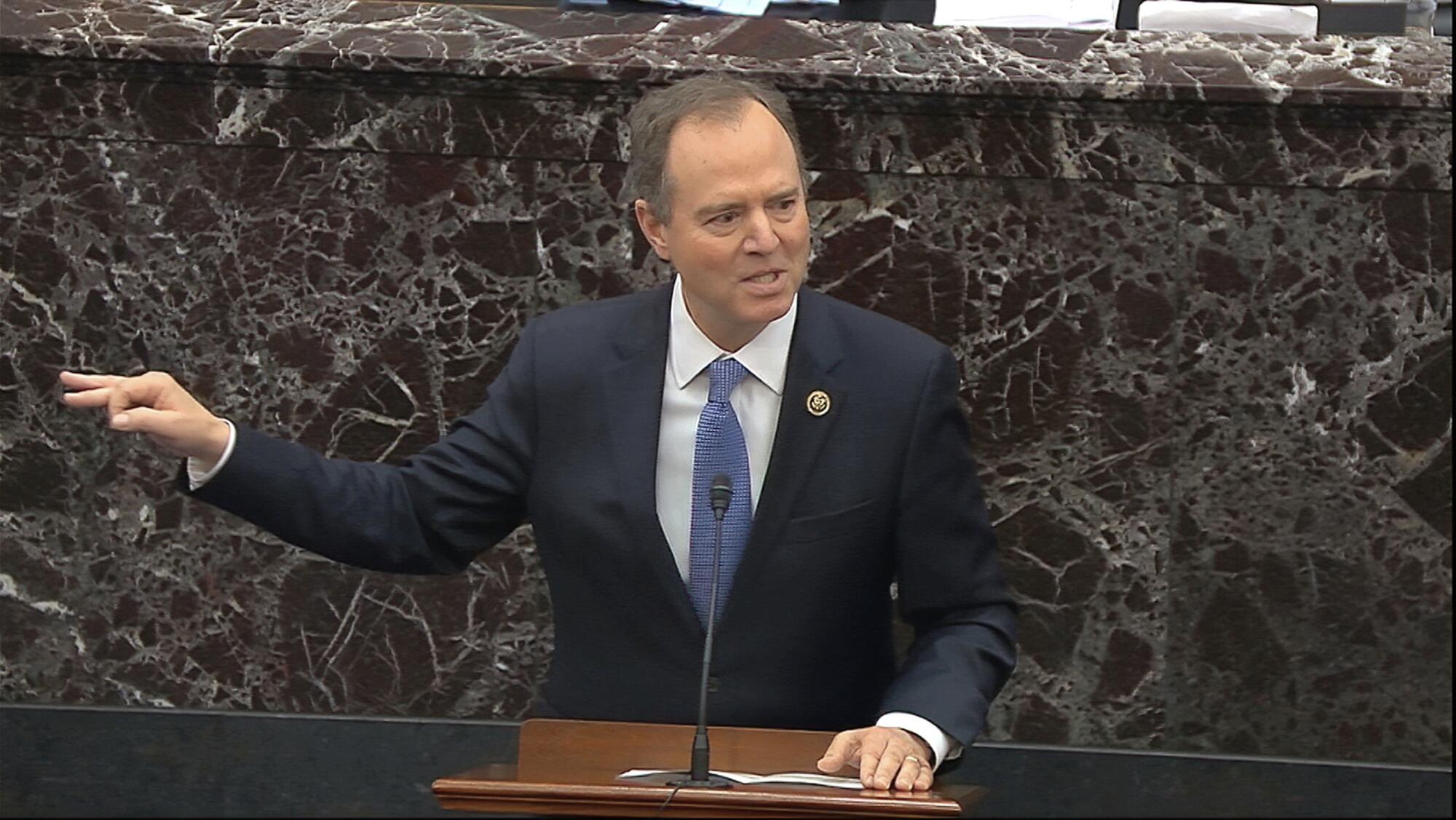

When Rep. Adam B. Schiff stood before the U.S. Senate on the final day of President Trump’s first impeachment trial, he reprised a familiar role: prosecutor.

The former assistant U.S. attorney hadn’t tried a case in more than a decade, but he was surprised how quickly the muscle memory came back. Wearing a crisp blue suit, the Burbank Democrat launched into a lacerating closing argument, trying to convince senators that Trump lacked the integrity, morality and temperament to remain in the White House.

“He has betrayed our national security, and he will do so again. He has compromised our elections, and he will do so again,” Schiff said. “You will not change him. You cannot constrain him. He is who he is. Truth matters little to him. What’s right matters even less. And decency matters not at all.”

The Senate ultimately voted to acquit Trump. But Schiff’s leading role in the historic proceeding has become etched in the nation’s political psyche, lionizing him among fellow Democrats, demonizing him among Republicans and seeding his 2024 campaign for the U.S. Senate.

The roots of Schiff’s tough-on-Trump persona go back to the 1990s, when the former federal prosecutor won a seat in the California Legislature as a law enforcement Democrat. In his earliest days in Sacramento, he pushed to increase some penalties, including for young offenders — an approach to criminal justice that is anathema to many progressives today.

Though the pursuit of justice has always been a driving force for Schiff, his attitude toward how justice should be applied, and to whom, has changed. In Congress, he has worked on gun control, police misconduct and investigations into Russia’s support for Trump’s 2016 campaign and into the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

His time as a federal prosecutor, the 63-year-old Schiff said this week, taught him “the importance of upholding the rule of law.”

“That’s been a core conviction for me,” he told The Times in a phone interview. “And that training came in much more handy than I would have ever imagined during the era of Trump.”

After the 1993 murder of Polly Klaas, a 12-year-old from Petaluma who was kidnapped by a man with a long criminal history, California enacted harsher sentencing requirements. In 1994, Republican Gov. Pete Wilson signed the so-called three-strikes law, which doubled the normal sentence for an offender’s second felony conviction and raised the penalty for a third conviction to 25 years to life. More than 70% of California voters supported the three-strikes law at the ballot box that fall.

Back then, Schiff was working as an assistant U.S. attorney in Los Angeles. He handled several high-profile cases, including the third trial of Richard Miller, a former FBI agent who was convicted of passing classified documents to the Soviet Union.

The experience taught Schiff how to conduct a complicated investigation into a white-collar crime. In a not-too-subtle jab at Trump, Schiff said he also learned the ways of Russian tradecraft, including “how they target people who are of poor moral character, who are philanderers, who are obsessed with money.”

::

During his race for the state Senate in 1996, Schiff fought his well-funded Republican opponent’s attempts to paint him as soft on crime. He campaigned on his support for the three-strikes law and the death penalty. His election was a victory for California Democrats, who increased their majority in the Legislature, as well as a personal victory: Schiff had run for office, and lost, three times before.

He arrived in Sacramento in 1997 as the youngest member of the Senate — determined, he said, to deter crime rather than just prosecute crimes that had already been committed.

Nearly 40% of the 142 bills Schiff introduced during his four-year term were related to policing, criminal procedure and public safety, including efforts to stiffen penalties for some offenses by children, to build and renovate juvenile halls, and to expand crime-prevention services for at-risk teenagers, a review of his legislative history shows.

“Like many Democrats, including President Biden, we wouldn’t strike the same balance today,” Schiff said. “My priority then, and my priority now, has always been to keep Californians safe and keep our communities safe. ... Some of the sentencing policies of the ’90s didn’t do much to reduce crime, but they did a lot to increase incarceration. I don’t think that’s the right balance.”

Schiff’s long legislative history is both an advantage and a liability as he vies for an open U.S. Senate seat following the death of Dianne Feinstein. His evolution on criminal justice issues hews with the leftward swing of California Democrats, who have signaled through statewide ballot initiatives and the election of progressive prosecutors that the state’s “tough on crime” era is over.

But after decades of public opinion steadily shifting away from the policies of the ’90s, the pendulum “seems to be swinging slightly back,” said Dan Schnur, a former Republican strategist who teaches political communication at USC and UC Berkeley. He pointed to recent debates over changes to Proposition 47, the 10-year-old law that reduced some felonies to misdemeanors — discussions that he said “would not have taken place several years ago.”

If the Senate race had occurred in 2020, amid the nationwide upheaval and demands for criminal justice reform that followed the Minneapolis police murder of George Floyd, Schiff’s background as a prosecutor and a self-described law enforcement Democrat “might end up being much bigger issues,” Schnur said.

Progressive criminal justice advocates have accused Schiff of pushing policies that were overly punitive, even by the standards of the ’90s.

In early 2021, Schiff supporters began floating his name as a possibility for California attorney general after then-Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra was tapped to become Biden’s secretary of Health and Human Services. When criminal justice activists caught wind of the effort, they sent a searing open letter to Gov. Gavin Newsom decrying Schiff’s track record and describing him as “not only supportive of, but deeply invested in, creating our current system of incarceration.” Newsom instead picked state Assemblymember Rob Bonta, an advocate for abolishing the death penalty and eliminating cash bail.

But Schiff was far from being out of step with his party, said former San Fernando Valley lawmaker Bob Hertzberg, who chaired the Assembly’s Public Safety Committee at the time. He said Schiff was “middle of the road” among the Democrats of the late ’90s.

“Everybody was doing tough-on-crime stuff. It was a different world,” Hertzberg said. Their constituents were worried about surging crime, fueled in part by the crack cocaine epidemic. In the early ’90s, the city of Los Angeles alone saw more than 1,000 homicides a year.

Some of Schiff’s earliest and most punitive bills didn’t become law, including one that sought to try children as young as 14 as adults in criminal court in murder and rape cases. Nor did a bill that would have required that children who committed serious offenses at school be sent to juvenile detention or military-run “boot camps.”

“He wasn’t just a bystander in the ’90s, getting swept along in the punitive approach to public safety,” said USC law professor Jody Armour. “He was really at the vanguard — one of the leading voices in promoting those kinds of policies.”

Schiff also introduced bills to clarify and expand the state’s three-strikes policy and lift the five-year limit on sentencing enhancements for nonviolent crimes, opening the door to longer prison sentences. Both became law.

The only 2024 statewide electoral contest is for Senate and includes Reps. Katie Porter, Barbara Lee and Adam B. Schiff along with former Dodger Steve Garvey.

In 2000, Schiff’s last year in Sacramento, Democratic Gov. Gray Davis signedthe Schiff-Cárdenas Juvenile Justice Crime Prevention Act. The bill, which set aside $121.3 million annually for local policing and another $121.3 million for programs aimed at curbing youth crime and delinquency, was believed to be the country’s largest source of funding at the time for youth crime prevention and intervention.

Democrats in Sacramento had decided that juvenile justice reform was “an area where the voters would be with us,” even if the state didn’t support overhauling the three-strikes law, said then-Assembly Speaker Antonio Villaraigosa. Efforts to pay for anything other than incarceration were “progressive stuff,” he said.

U.S. Rep. Tony Cárdenas, then a member of the state Assembly representing the San Fernando Valley, said that when he backed juvenile justice reform, some of his colleagues ribbed him for supporting what they called “hug-a-thug” programs. Cárdenas, who has endorsed Schiff in the Senate race, said he wanted Schiff to co-sponsor the bill because his background as a prosecutor would help deflect criticisms that alternatives to incarceration were soft on crime.

Counties used the funding for gang-intervention efforts, drug counseling, mental health screenings and a wide array of other services, including after-school and nonprofit programs. Studies later found that children in those programs were less likely to be arrested or incarcerated and more likely to complete any court-ordered community service.

::

Since he arrived in Washington in 2001, after what was then the most expensive House race in history, Schiff has mostly left behind courtroom issues in favor of bills focused on broader law enforcement and criminal justice policies, including police accountability.

In 2011, he pushed the FBI to widen its use of familial DNA — in which investigators trying to identify crime suspects through their genetic material search for potential relatives in government databases. And after a national scandal erupted over a years-long backlog of more than 13,000 rape kits at the Los Angeles Police Department and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, Schiff secured funding to help process them.

As grainy cellphone videos of police shootings began to appear, shocking “the conscience of the country,” Schiff said, he became convinced that the U.S. needed police reform. After Michael Brown was shot to death by a Ferguson, Mo., police officer in 2014, Schiff led members of Congress in pushing for a federal grant program to equip police departments with body-worn cameras.

Editor’s note: We turned our California Politics newsletter into the L.A.

In the summer of 2020, amid the mass protests calling for criminal justice reform after Floyd was killed by police, Schiff made the rare move of withdrawing his endorsement of then-L.A. County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey in her contentious reelection fight against progressive challenger George Gascón. Since his election, Gascón has faced two failed recall attempts. Schiff has not endorsed Gascón’s bid for reelection.

Schiff voted for bills that would have decriminalized marijuana nationally and ended the federal sentencing disparity between drug offenses involving crack and powder cocaine. He was also one of 190 original co-sponsors of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which would ban no-knock warrants in federal drug cases and create a national database of complaints and records of police misconduct.

Schiff’s view on the death penalty is among his biggest changes since his days as a federal prosecutor. He said he wrestled with the issue for years and no longer supports capital punishment.

“There was certainly a time when I supported the death penalty for those who killed cops and those who killed kids,” Schiff said this week. But over time, he said, he “came to lose confidence” in how the law was applied, in part because DNA evidence showed that “too many people on death row were innocent,” and because executions disproportionately affected people of color.

::

Those difficult issues, however, were not what launched Schiff into national prominence.

After Democrats took back the House in 2018, he became chairman of the Intelligence Committee. He developed a national profile through his clashes with Trump and regular appearances on cable news shows.

Then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi appointed Schiff as lead manager of Trump’s first impeachment trial. Democrats had accused Trump of abusing his office when he asked Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to investigate Biden and his son Hunter while Trump was withholding crucial military aid. A second article of impeachment accused Trump of obstructing Congress’ investigation into the alleged scheme by refusing to release subpoenaed documents or to allow current and former aides to testify.

Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-San Jose), who worked as an impeachment manager alongside Schiff, said he was thorough and professional, and had a “tremendous command of the facts.” Trump’s animosity and the death threats that the team received, she said, “steeled [Schiff] to stand up for the truth.”

Not visible during the televised hearings, Lofgren said, was that Schiff was in excruciating pain due to a dental emergency. Schiff said he alternated between Tylenol and Advil every four hours until he could make it to the dentist for a root canal the weekend before closing arguments. At one point, he recalled, fellow impeachment manager Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) gave him a pep talk: “Hey, this is like an NBA championship. You got to play through the pain.”

Republicans reclaimed the House majority in 2020, and in 2023 removed Schiff from the Intelligence Committee.

He had said publicly that there was “significant” and “compelling” evidence of collusion between Trump’s campaign and the Kremlin in the 2016 election.

Robert S. Mueller III, the Justice Department’s special counsel in that case, found that Russia had intervened on the Trump campaign’s behalf, and that the campaign had welcomed the help. But Mueller did not recommend that the Justice Department charge any Americans.

Last year, the GOP-led House voted to censure Schiff, approving a resolution that said he had “misled the American people and brought disrepute upon the House of Representatives.” As then-Speaker Kevin McCarthy read out the vote count — 213 to 209, along party lines — Democrats crowded the House floor, chanting: “Shame! Shame! Shame!”

Republicans continue to accuse Schiff of being unfit to hold public office. During Senate candidates’ first debate last month, GOP hopeful Steve Garvey told Schiff: “Sir, you lied to 300 million people. You can’t take that back.”

But to Schiff, the censure is proof of a job done right.

After its passage, he rose before his colleagues and said:

“Today, I wear this partisan vote as a badge of honor, knowing that I have lived my oath, knowing that I have done my duty to hold a dangerous and out-of-control president accountable, and knowing that I would do so again, in a heartbeat, if the circumstances should ever require it.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.