Mint sauce

THIS weekend being Easter, many Americans will sit down to a Sunday dinner of roast lamb. And that will be the last time they try the meat until the same time next year.

Lamb is to this holiday what turkey once was to Thanksgiving, something served once a year and, for many, eaten more for ceremony than for pleasure.

This isn’t idle speculation; I’ve got statistics to back me up. Americans’ annual per capita consumption of lamb stands at four-fifths of a pound. Because a 5-pound leg will serve about eight people, that works out to about a dinner a year, give or take a sandwich the next day.

But if it is prepared the right way, what a dinner that will be. There is no roast better than a leg of lamb -- golden brown skin, moist pink flesh. The flavor is a compelling blend of something like beef but with a distinctive, gamy note thrown in. The aroma is entrancing.

What’s more, lamb marries so well with so many other flavors: Garlic seems to become sweeter when cooked with it and black olives meatier. Lamb wears capers like diamonds and the perfume of fresh herbs like some beautiful women wear Chanel No. 5.

This is the thing that has always puzzled me: Why is it that one of the most flavorful meats you can buy is so often ignored? If we have embraced turkey as a year-round ingredient, can’t we do the same for lamb?

The reason more Americans don’t love lamb, I have come to believe, is that most of the time that Easter leg is roasted wrong. That’s not just the fault of the cooks involved, but also of many of the recipes they follow.

The problem is pretty simple: Most recipes call for leg of lamb to be served underdone. Thumb through your library -- you’ll find cookbooks calling for a leg of lamb to be served at 120, 115 and even 110 degrees.

This, in my opinion, is horrible advice. Leg of lamb at these temperatures is stringy in texture, even gristly. To be at its best, lamb needs to be cooked to the high end of the medium-rare scale, even to low medium. That means temperatures from 130 to 135 degrees.

That may sound heretical -- somehow we’ve come to associate bloody meat with true gourmandism -- but give it a try.

The language of done-ness is notoriously vague -- one person’s medium rare is another’s nearly raw. So let’s be explicit: When leg of lamb is cooked to around 130 degrees, the meat is still pink and moist but the stringy tendons have begun to melt and the spongy flesh has begun to firm.

So if this temperature works so well, why do recipes recommend lower ones? It’s probably a combination of several factors.

First, in the United States, lamb had for years traditionally been over-, rather than undercooked, which is even worse. In reaction to decades of Grandma’s gray, dried-out lamb (well-done in name only), cookbook authors (and therefore cooks) have more recently gone to the opposite extreme.

There might be anatomical confusion as well. Lamb chops are often served rare to medium rare, so it might seem like a good idea to do the same with the leg. But that’s ignoring the differences between the two cuts.

Chops come from the loin muscle, which gets very little exercise and is naturally tender. Legs are heavily worked, even in lambs, and so they are full of fibrous muscles and connective tissues that need to be cooked to a higher temperature to become palatable.

Finally, there just might be some confusion about what exactly is meant by “lamb.” Of course it means a young sheep, but just how young?

Especially around Easter, when people talk about lamb, they’re often thinking of newborn or milk-fed lamb, the kind that is sometimes called spring lamb. These are only weeks old. They have very fine flesh (and very mild flavor), and they need to be cooked extremely pink -- to medium rare at the very most -- to avoid drying out.

A rare find

BUT spring lamb is very hard to find these days, particularly in the United States. In fact, unless you’ve got a connection in the wool or sheep’s milk cheese business, you’ll probably never see it. I have a friend in Northern California who has a friend who has a friend who ... well, anyway, he is able to get one spring lamb a year.

The loin chops are about the size of a silver dollar, and they are absolutely delicious grilled very quickly over hardwood.

The lamb the rest of us get can be as much as a year old. Different countries have different methods for determining the exact maturity. In the United States, inspectors check the degree of calcification in the knee; in New Zealand, where a rapidly increasing percentage of our lamb comes from, they count the number of adult incisors.

This isn’t a lesser lamb. In fact, it has a more fully developed flavor than spring lamb. But it is lamb that has been around the block a time or two, at least enough to acquire fully developed leg muscles, which require a little more cooking.

Beyond the lamb stage, sheep mature first into hogget -- essentially 1 to 2 years old -- and then to mutton. These animals can also be fine eating, but in the United States they are just as hard to find as spring lamb.

In the U.S., the choices are much more limited -- basically, where the lamb was grown and whether you want that leg on the bone.

Most of the lamb we buy comes from either Colorado or Australia and New Zealand. And more and more of it is coming from the latter. Imported lamb from New Zealand and Australia makes up more than 40% of what we eat. In fact, even though California is the second-leading lamb-producing state in the country, finding local lamb can be tough (Superior Farms, the largest producer in the state, says its meat is available at Smart & Final and Wal-Mart).

Bristol Farms, which has always sold domestic lamb, says it probably will switch to New Zealand meat in the near future. Its biggest competitor, Whole Foods, is already selling it.

“We’ve been selling domestic lamb since I’ve been with the company, that’s going on 17 years, and changing is not something we do lightly,” says Bristol’s senior meat manager Pete Davis. “But we’ve done extensive testing, including blind taste tests, and the New Zealand lamb always won. So we’re probably going to switch in the next couple of months.”

The imported lamb is also cheaper.

Indeed, New Zealand lamb is one of the more interesting success stories in global agriculture. Just 20 years ago, the lamb industry there was in the pits. The meat wasn’t much good, and there was way too much of it to get a decent price.

What turned things around, according to a recent paper by two Iowa State University agricultural economists, was the lifting of government subsidies that underwrote much of the cost of sheep farming.

Without subsidies, the size of New Zealand’s sheep herd shrunk dramatically. (Relatively speaking anyway: There are now 10 sheep per person in New Zealand, whereas in 1982 there were 20.) The smaller individual herds were concentrated onto only the best pastures, and meat quality rather than quantity became the producers’ prime focus.

In 2005, the U.S. imported more than 180 million pounds of lamb and sheep, 99% of that from Australia and New Zealand. That’s almost half of all the lamb we eat -- as compared with only a little more than 10% in 1990. Even Superior Farms has a subsidiary called Country Meadow that imports Australian lamb.

Lamb, American style

AUStralian and New Zealand lamb tends to be smaller than American lamb. The American Lamb Council brags that domestic rib chops are 38% bigger than imported chops. American lamb also seems to be more variable in flavor; whereas New Zealand and Australian lamb is fed entirely on grass, much American lamb is finished on grain, which gives the meat a milder taste.

Other than that, your only choice in lamb will be whether you want the leg whole or with the bone removed and tied into a roll. Either can be roasted, and they can be used interchangeably in recipes except for a slight difference in timing. Because the bone conducts heat, the boneless roast will take slightly longer to cook.

For most roasts, I prefer to leave the bone in, strictly for appearance’s sake (though boneless legs, untied and opened flat, are superlative for grilling as they offer so much surface area to sear a good crust).

If you’re roasting with the bone in, look for legs that have had the hip bone removed for easier carving (as is automatically done at some markets), or have the butcher remove it. For a nicer presentation, I also “french” the shank -- that is, remove the last 1 1/2 to 2 inches of meat all the way around the bone. A butcher can also do this.

Roasting a leg is about as simple as good cooking can get. Season it liberally with salt and pepper. Rub it with olive oil. Brown it in a 450-degree oven for 20 minutes, and then reduce the heat to 325 to let it cook through to an interior temperature of 130 degrees. Let it rest so the juices can redistribute and then serve.

Roasted this way, a leg of lamb is a majestic piece of meat. Anything else you do to it is an elaboration -- not that that would be a bad thing, necessarily.

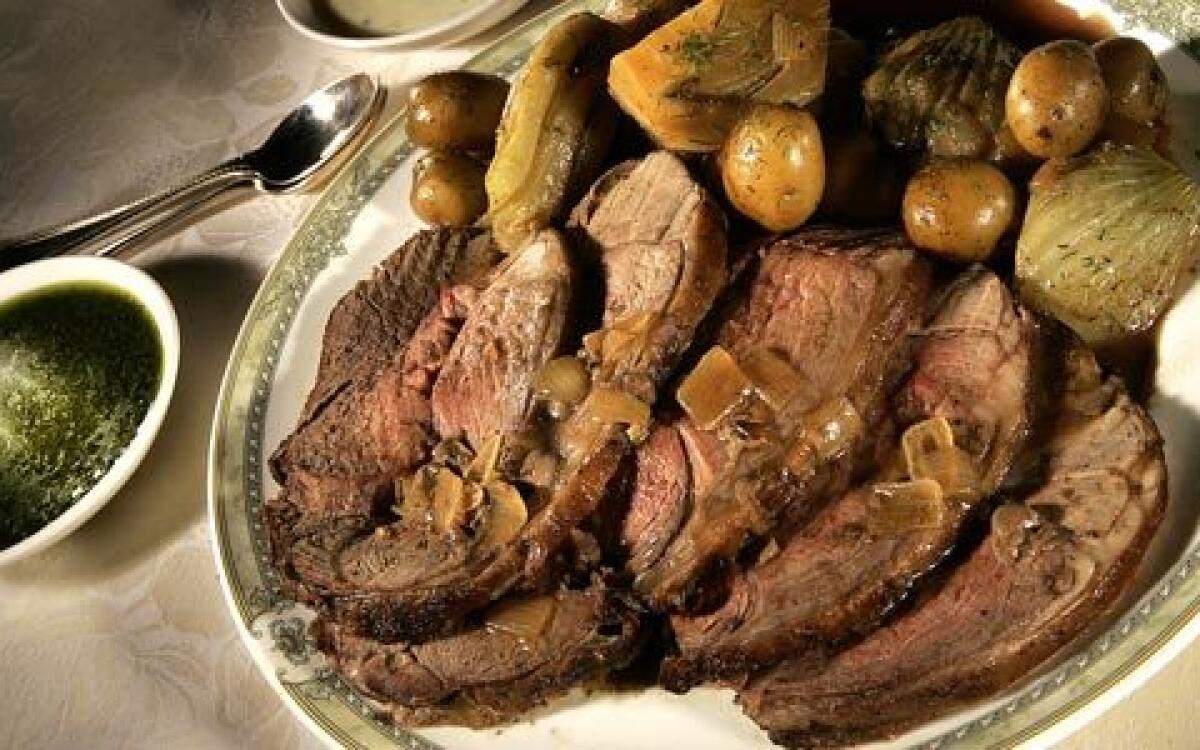

Pot roasting is usually quite distinct from oven roasting -- it normally means cooking a big piece of meat in a covered pot until it’s falling apart. But you can make a delicious roast by braising the leg only briefly on a garlicky bed of fennel and potatoes before removing the lid to finish cooking. This way, the perfume of the vegetables penetrates the meat quickly, but you still get the nice brown crust of a roast.

With either type of roast, you might like a sauce. You can make a simple jus while the lamb is resting by pouring off most of the fat from the roasting pan, sizzling some shallots in what is left and deglazing with red wine. Taste, and if the wine is too intense, dilute it with a little water.

Or make a mint sauce. I really like this adaptation from British chef Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall’s upcoming “The River Cottage Meat Book.” Shake up chopped mint and minced shallot in vinegar and thicken it with yogurt. It’s about as far from the stereotypical super-sweet English mint jelly as you can get -- there’s just enough sugar to take the edge off of the acidity.

Italian salsa verde is usually made with a mixture of parsley and basil, but for serving with lamb, make it with parsley and mint. This is an exuberant sauce, like a very gutsy pesto, super-charged with pounded anchovies and capers.

On the other hand, maybe you don’t want a sauce. One of the best lamb roasts I’ve made recently was served without one. The twist was that before roasting, I studded the leg with pieces of anchovy, sprigs of rosemary and splinters of garlic.

The effect was a little disconcerting at first; the regular tufts of herbs sprouting from the skin made the lamb look a little like it had just gotten a hair transplant. But during the roasting the anchovies and garlic melted into the meat, giving it a rich savor.

Even if the right approach to roast lamb wins over more Americans, we’d have to do a lot to catch up to New Zealanders -- they eat more than 50 pounds of lamb per person every year.

But at the very least, maybe we can get out of our only-on-Easter rut.

Put the mint, shallots, vinegar, sugar, salt, mustard and oil in a small jar with a tight-fitting lid. Seal and shake well to combine. Add the yogurt and shake well again.

Get our Cooking newsletter.

Your roundup of inspiring recipes and kitchen tricks.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.