Navy faces daunting task of counting desert petroglyphs

- Share via

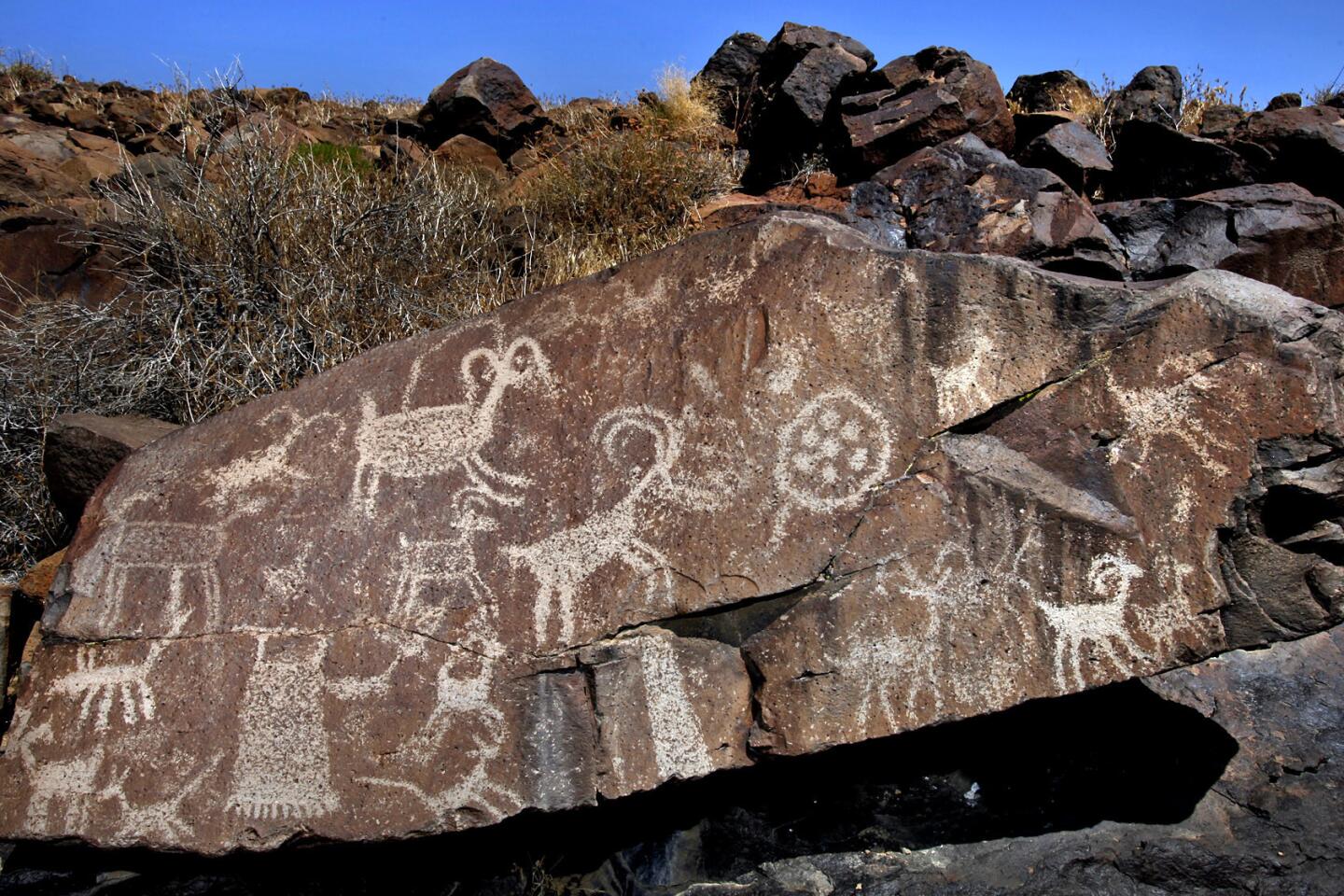

Reporting from Ridgecrest — Archaeologists know it as Renegade Canyon, a lava gorge in desert badlands with more than 1 million images of hunters, spirits and bighorn sheep etched in sharp relief on cliff faces and boulders.

But this desert is in the heart of the China Lake Naval Air Weapons Station, and it is where the Navy and Marines develop and test advanced bomb and missile systems.

Safeguarding the canyon and other troves of rock art from stray bombs and vandalism has been a priority since the Mojave Desert base was established in 1943. Now, the Navy is gearing up for a daunting new mission: creation of the first comprehensive inventory of the largest concentration of petroglyphs in the Western Hemisphere.

The effort comes at a time of renewed interest in the spectacular displays in the Coso Range of southern Inyo County, just east of the Sierra Nevada. This year, the nearby city of Ridgecrest, best known as home of the weapons testing center, is rebranding itself as a mecca of rock art and preparing to hold its first petroglyphs festival. A documentary called “Talking Stone: Rock Art of the Cosos” will premiere July 1 on PBS SoCal.

The Navy is rounding up funding and equipment to begin its inventory next year in the upper reaches of Renegade Canyon, one of 4,000 significant prehistoric sites on the base.

Mike Baskerville, chief archaeologist at the 1.1-million-acre base 130 miles northeast of Los Angeles, said the project will take years to complete even with the help of GPS units, high-definition cameras and teams of archaeologists.

Eventually the information they gather will be posted online. “Native Americans, in particular, will be able to tell their children, ‘These images are windows into the minds and culture of our ancestors,’ ” Baskerville said.

On a recent trip to the petroglyphs, Navy Capt. Rich Wiley, the new commanding officer at the base, put on sunglasses for a better view of human forms with arrows and spears, human-like spirits with raven and quail heads and myriad lizards, snakes, spirals, radiating circles and arrays of dots.

In one of the most peculiar tableaus, stick figures in a long line walk across the face of a massive boulder, turn the corner and keep marching.

Archaeologists believe the pictorial outbursts chipped and chiseled by the Coso Shoshone peoples dating back 15,000 years probably played a crucial role in prayers for bountiful herds, plentiful rain and hunters’ success in bagging game — first with throwing sticks called atlatls and, beginning about 1,800 years ago, with bows and arrows.

Today, the Navy fires laser-guided bombs and Tomahawk cruise missiles in nearby testing ranges. A running joke on the base goes like this: China Lake: 10,000 years of weapons technology.

Only about 5% of the base is dedicated to weapons testing, with the rest of the arid landscape protected as buffer and safety zones.

In 1964, the canyon, which is also known as Little Petroglyph Canyon, and another site known as Big Petroglyph Canyon, were listed as a National Historic District. In 2001, the district was expanded by 36,000 acres and dedicated as the Coso Rock Art National Historic Landmark, the only designation for such a resource on Department of Defense land.

In November, Ridgecrest will hold a petroglyph festival, a three-day event featuring a street fair and tours of Renegade Canyon and Lark Seep, another rock art hot spot on the base. In addition, the city has approved construction of a $6-million Petroglyph Park with replicas of the rock art in areas controlled by the Navy.

“The petroglyph festival will be our signature event,” Ridgecrest Mayor Dan Clark said in an interview. “We’re going to saturate this community with representations of rock art.”

That kind of talk intrigues David Whitley, an archaeologist and expert on the Coso region. “I find it remarkable that this rock art tradition is still meaningful to Native Americans, and to those of us who do not have direct ties to it,” Whitley said.

Sandy Rogers, curator at the Maturango Museum in Ridgecrest, said the images are becoming part of the region’s “common repertoire — I see them showing up on coffee cups, T-shirts, key chains, book covers and all kinds of other things.”

Rogers said the Navy should be thanked for being good stewards of the petroglyphs. Then he added with a laugh, “But they’ll never be able to catalog them all — there are just too many, and we keep finding more all the time.”

Twitter: @LouisSahagun