October begins water year with prospect of tighter restrictions

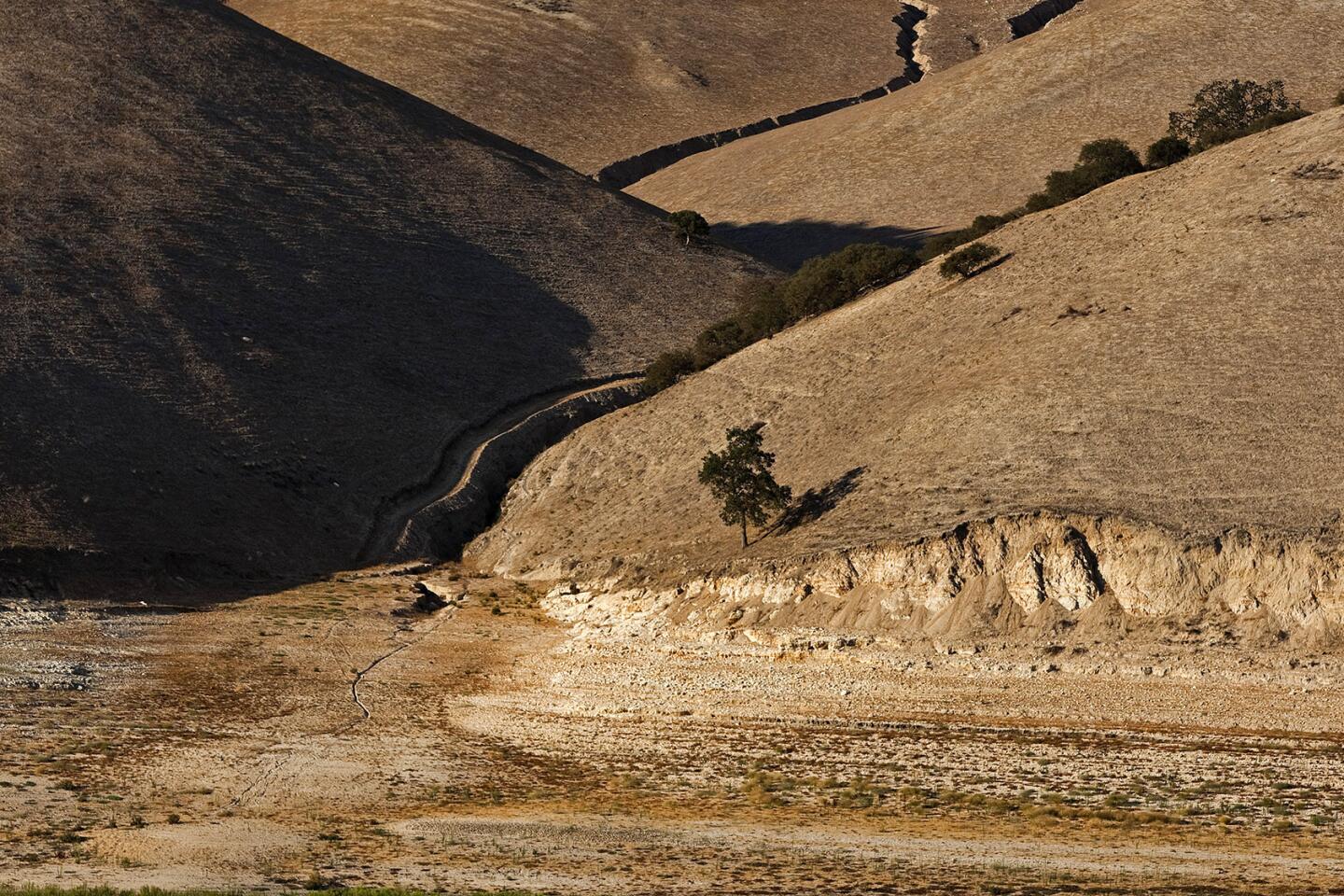

As the state ends the fourth-driest water year on record with no guarantee of significant rain and snowfall this winter, Californians face the prospect of stricter rationing and meager irrigation deliveries for agriculture.

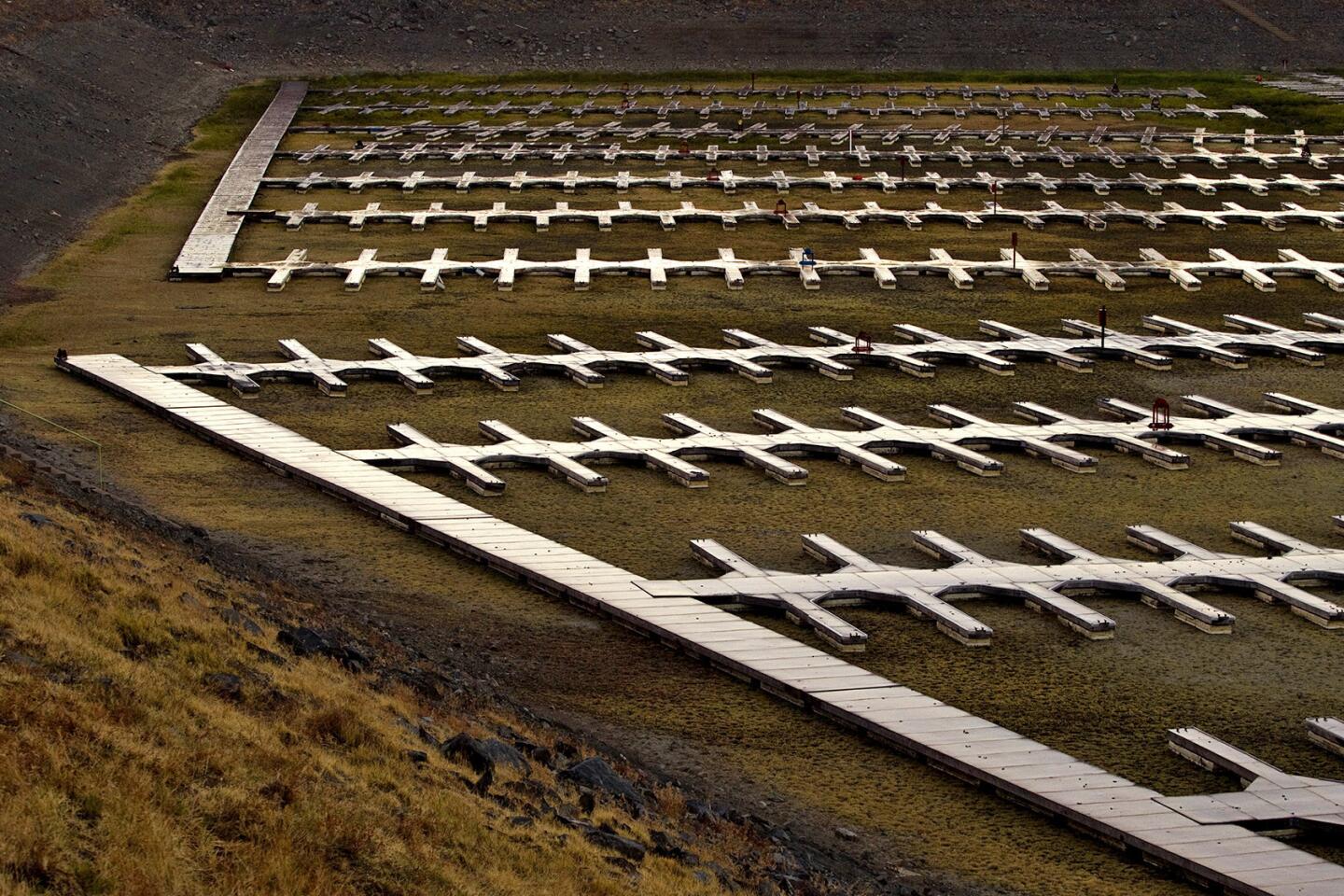

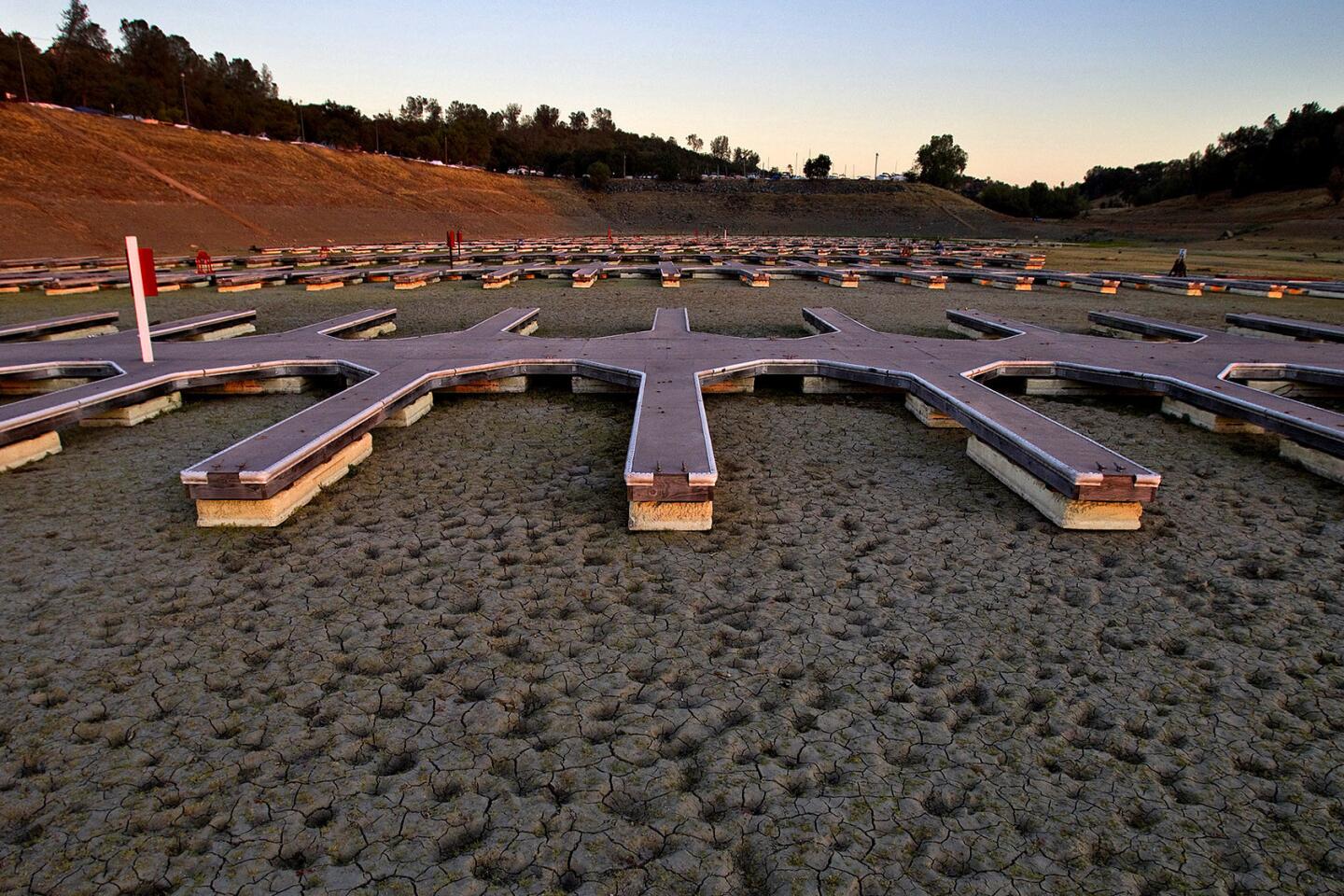

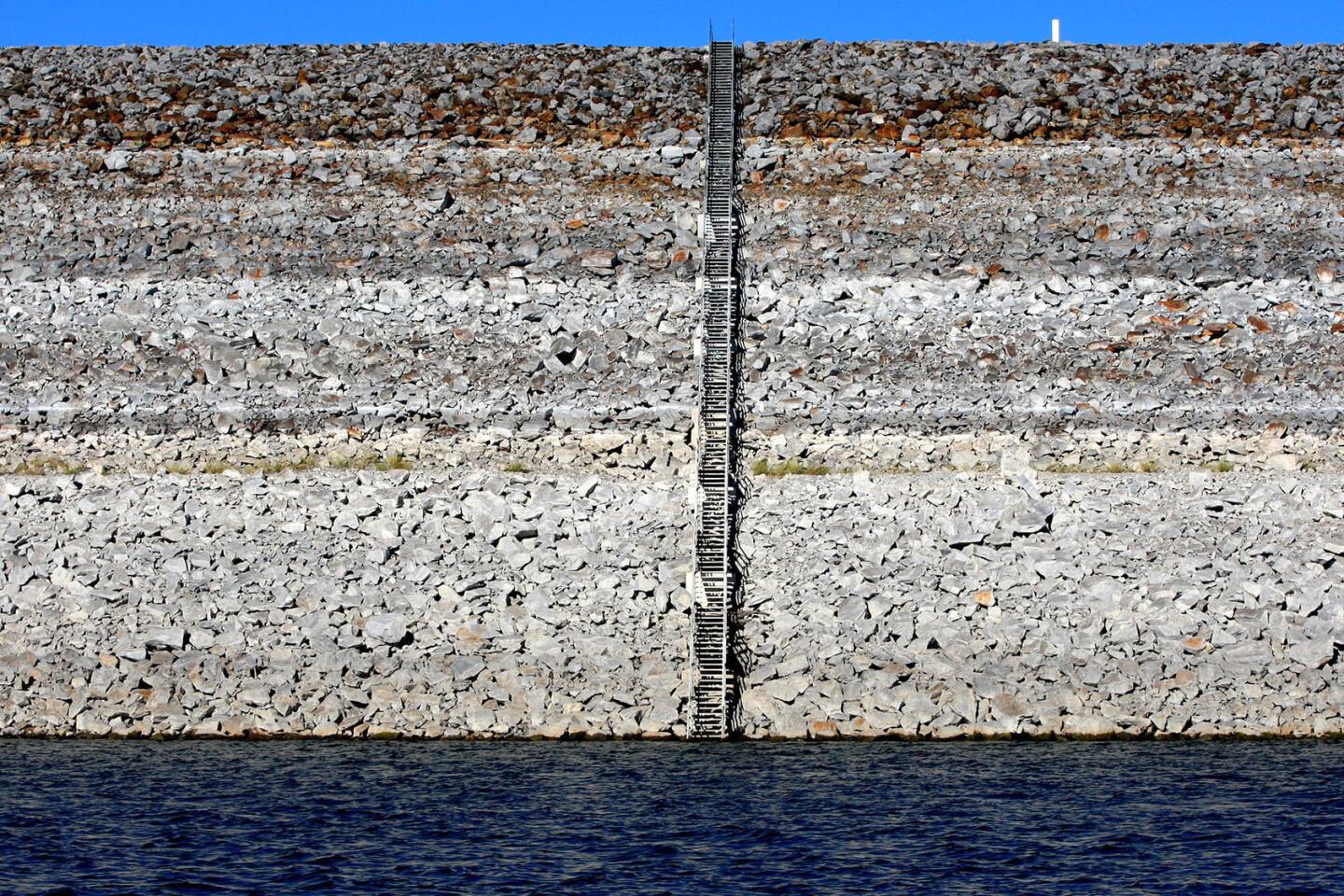

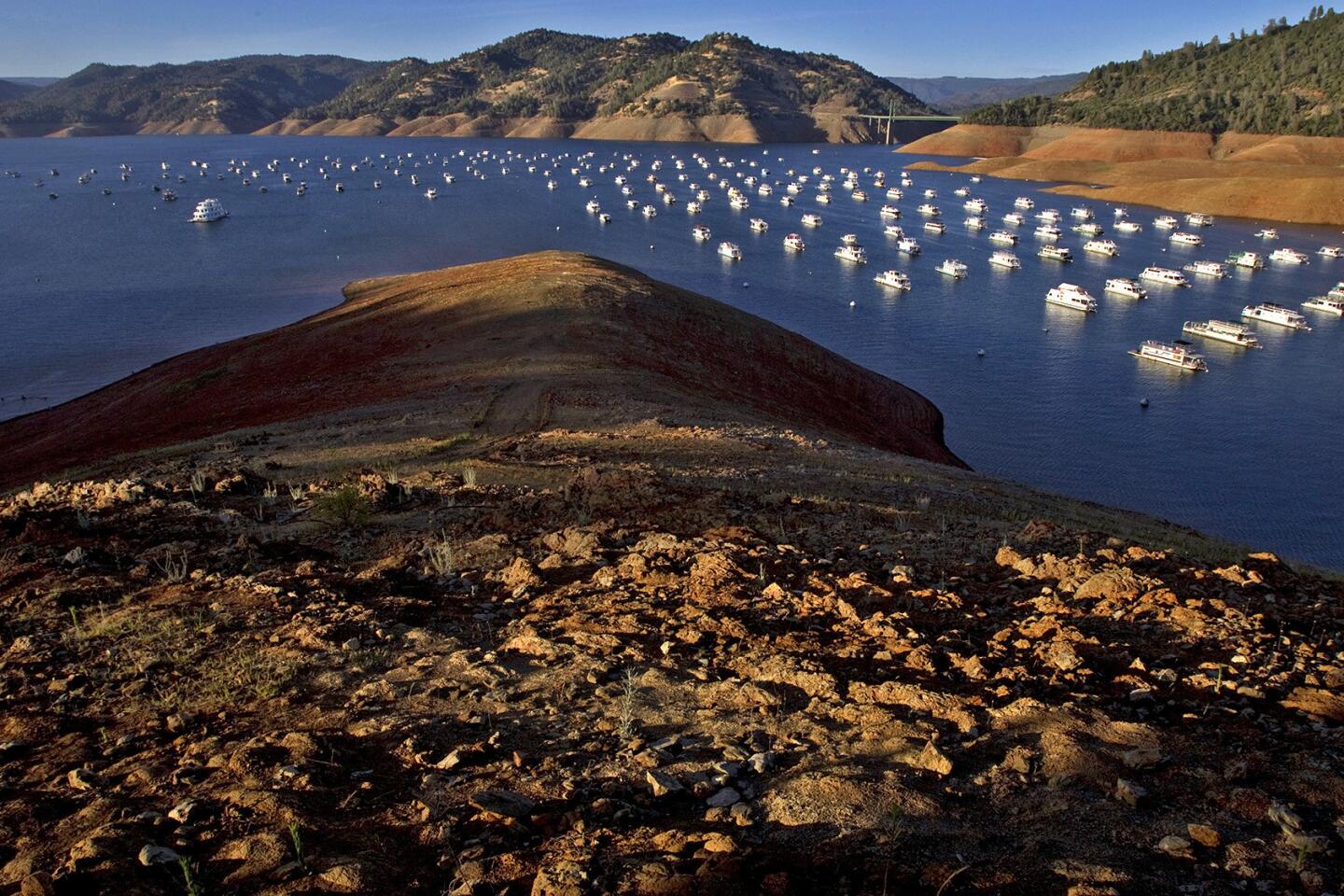

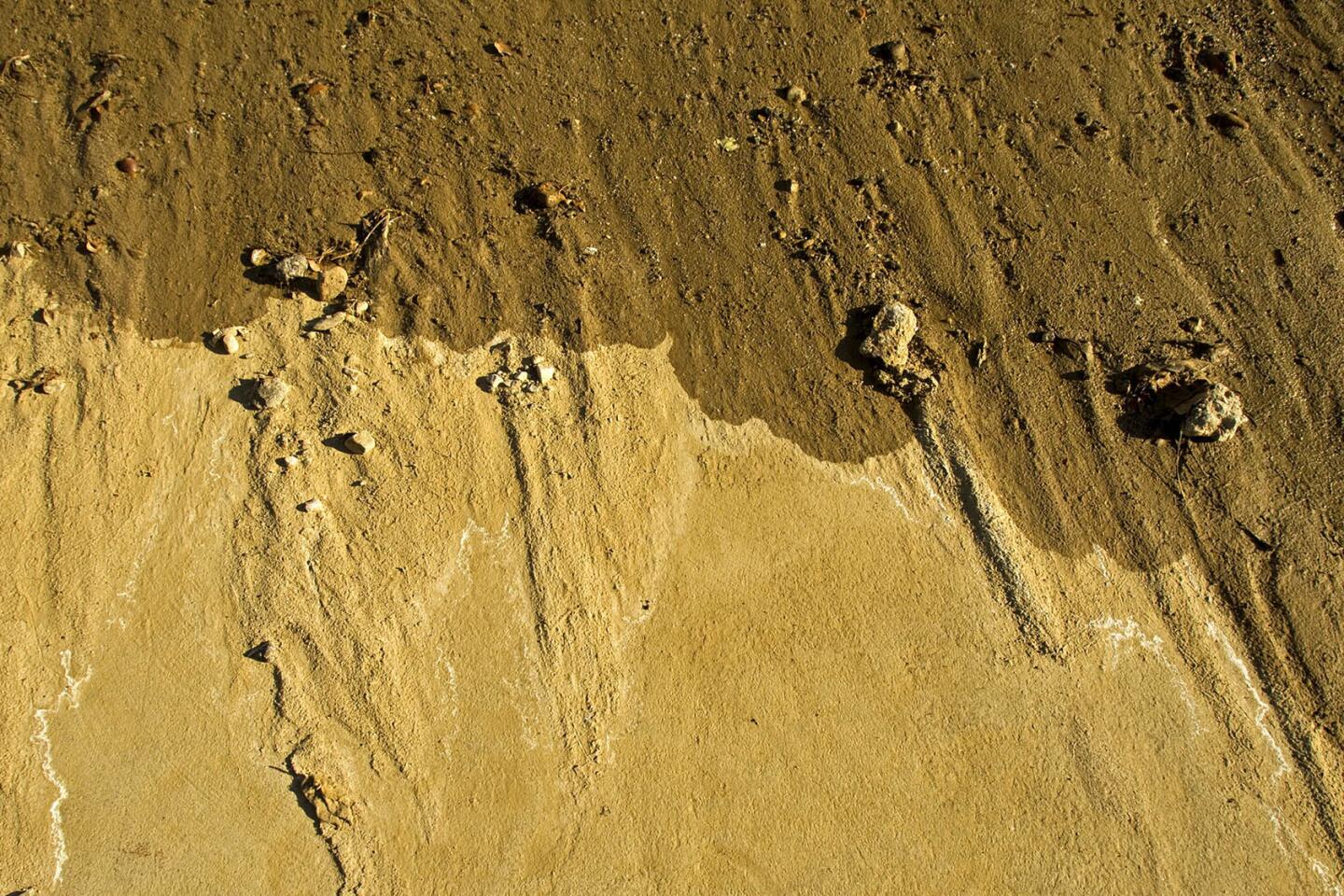

California begins a new October-September water year Wednesday with total reservoir storage at 36% of capacity, or 57% of average for this time of year.

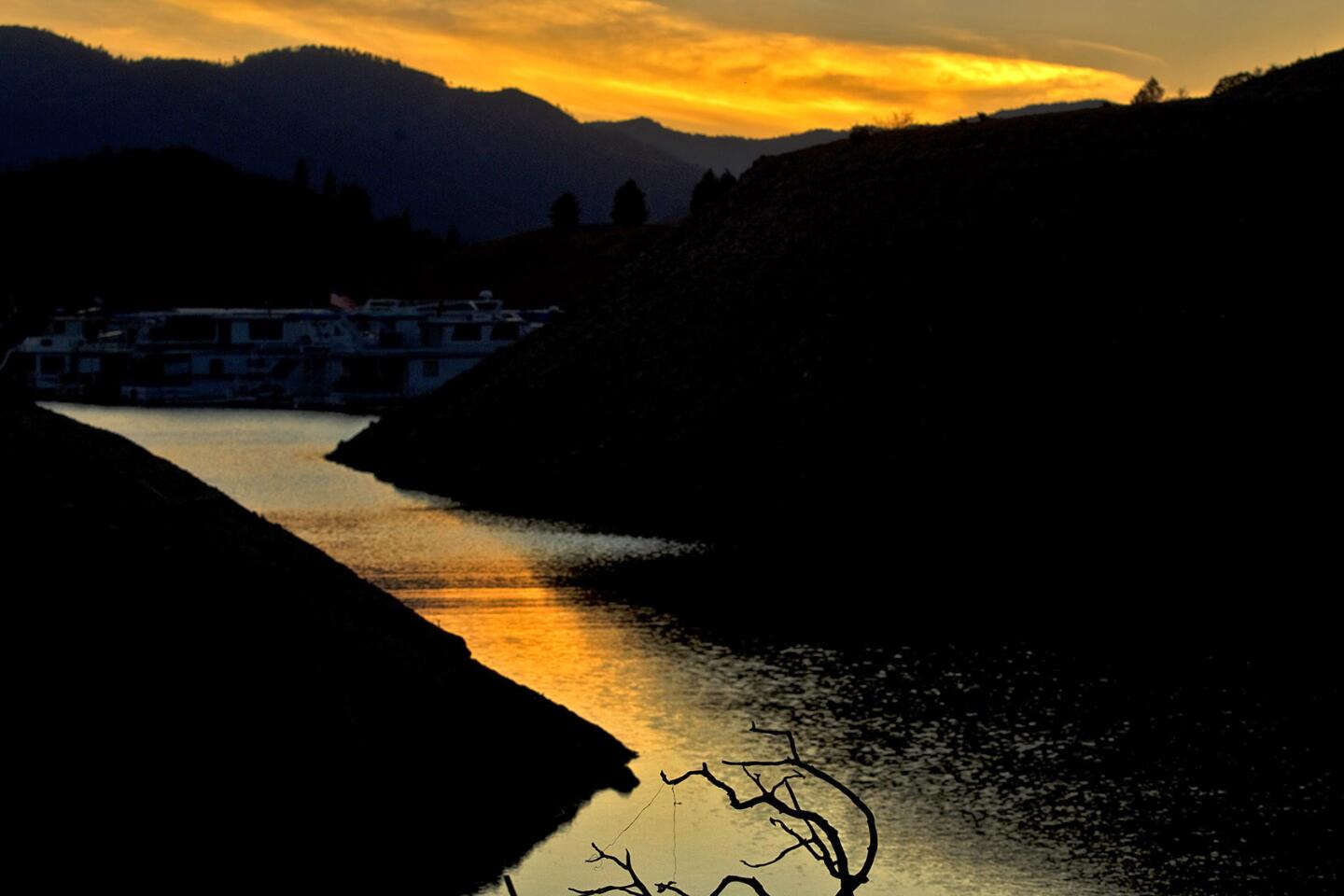

Although some private domestic wells have dried up and a scattering of isolated little communities are in danger of running out of supplies, the drought’s effect on most Californians has so far been modest. Another rainless winter would probably change that.

“In general, our big communities have very adequate water supply and good reserves,” said Mark Cowin, director of the California Department of Water Resources.

But if 2015 is a repeat of this year, “more people will feel the direct results of the drought in our cities,” he said. Cowin expects more mandatory rationing and water-use restrictions, more unplanted cropland and greater effects on fish and wildlife.

“I truly think the biggest impacts would be on the agricultural sector and the environmental sector,” he said.

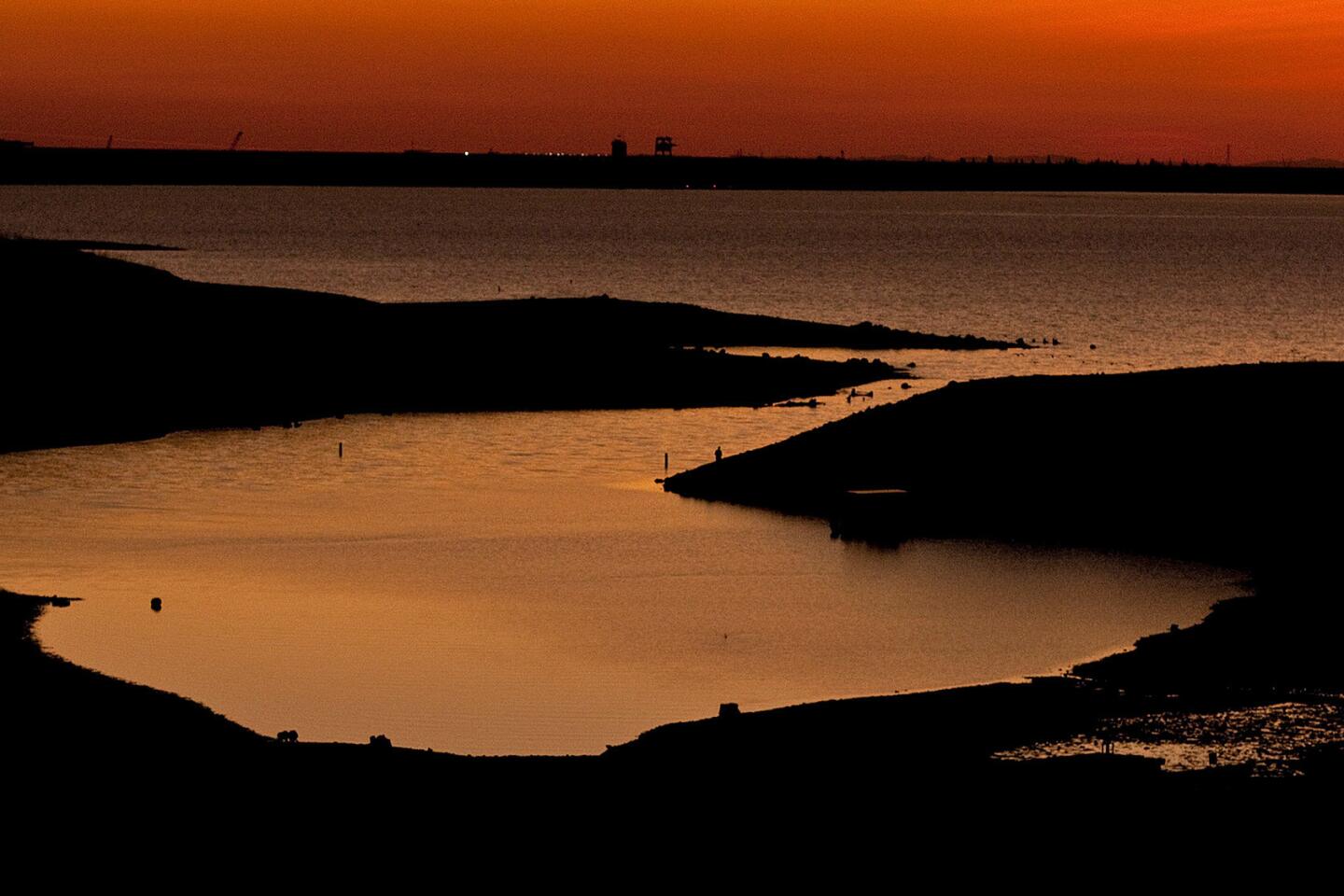

Migrating salmon that struggled this year would have a harder time reaching spawning grounds. Waterfowl would crowd into shrunken wintering grounds.

Drops in crop and livestock production, combined with the expense of increased groundwater pumping, are expected to cost farmers $1.5 billion this year. A dry 2015 would take a $1-billion bite out of Central Valley crop revenue, according to a UC Davis report.

Officials measure dry conditions in terms of the runoff that fills rivers and reservoirs statewide and is crucial to the water supply. The lowest runoff was in water year 1977 — when statewide storage was only about a quarter of capacity — followed by the drought years of 1924 and 1931 and now 2014, according to Maury Roos, the state’s chief hydrologist.

The level of Southern California’s big regional reservoir, Diamond Valley Lake, is falling by about a foot a week as the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California draws down imported supplies. The water district, which has water banked elsewhere and began the drought with record amounts of storage, expects to have depleted its non-emergency reserves by roughly half by the end of December.

Although the district is getting only 5% of its allocation of Northern California supplies this year, deliveries from Metropolitan’s other major source, the Colorado River, have filled the aqueduct that snakes across the Mojave Desert from the Arizona border.

“We expect to have a full Colorado aqueduct delivery next year as well,” said Debra Mann, the water district’s chief operating officer.

That leaves the Southland in a better position than other regions that are entirely dependent on California supplies.

Still, if nature is as stingy with rain and snow in 2015 as it was this year, Mann said Metropolitan “would definitely” consider rationing supplies to local agencies by increasing the price of water they buy over a base amount. That program was in place for 18 months during the 2007-2009 drought, when the agency cut its deliveries by a fifth, triggering local rationing.

The move would have a similar ripple effect next year, forcing local agencies to take more action to reduce demand. Los Angeles, which now limits the days and times of outdoor watering, can impose progressively tougher restrictions under its drought regulations.

Along with greater limits on outdoor use, the city could reduce the amount of water available to households at the lowest price. Under DWP’s existing tiered rate system, the more customers use above that base allocation, the more they pay.

“We have a pretty good ordinance in place and there are things that can happen as a result of that ordinance if the conditions warrant it,” said Nancy Sutley, chief sustainability and economic development officer of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

Despite severe cuts, and in some parts of the state the total elimination of government irrigation deliveries, farmers managed to plant the vast majority of the state’s cropland this year by pumping more groundwater and buying supplies from irrigation districts with senior water rights. That would continue if the drought persists, further depleting the Central Valley’s chronically over-pumped aquifer.

“One of the reasons that agriculture hasn’t done worse this year is because of the tremendous amount of groundwater withdrawal that took place,” Cowin said. “That’s essentially borrowing on tomorrow’s future. We’ll pay that price over time.”

Even a normal rainy season wouldn’t be enough to end the drought and refill reservoirs. And although the latest forecast from the federal Climate Prediction Center gives a 60% to 65% chance that El Niño conditions will develop this fall and winter, water managers know better than to count on it.

Twitter: @boxall