Gun injuries: Are they getting more deadly?

- Share via

New research suggests that between the years 2000 and 2013, the injuries sustained by victims of firearms violence grew both more severe and more deadly, even as mortality from other traumatic injuries declined.

Just days after the nation’s worst mass shooting took place at a nightclub in Orlando, Fla., the Journal of the American Medical Assn. on Tuesday published the findings of a study focusing on close to 30,000 trauma patients who were treated at a single hospital system in Denver. Tracking the types and severity of traumatic injuries in patients brought to the hospital over 14 years, the new research found that the death rate for hospitalized gunshot victims climbed an average of 6% every two years.

The rising fatality rates occurred against the backdrop of gunshot wounds that were also escalating in severity. Over the study period, ambulances brought in an increasing number of firearms victims with two or more bullet wounds and injuries over more regions of their bodies.

Injuries grew progressively more severe among victims of stabbing and pedestrian accidents as well. But unlike those hurt in firearms incidents, patients who were stabbed or run over were not progressively more likely to die of their injuries during the study.

See the most-read stories in Science this hour >>

“I doubt this is a failure of the trauma or emergency medical system” that transports injured patients to the hospital, said Brown University emergency physician Megan Ranney, who studies firearms injury.

Physicians and policymakers have refined practices both in hospital trauma care and emergency care in the field to improve the prognosis for trauma victims, added Ranney, who was not involved in the current study. “We’ve decreased fatality rates from every type of injury except guns,” she added, and why that is happening is a mystery, she said.

The new research comes against the backdrop of growing evidence that firearms violence is not only becoming more common; it is becoming more deadly. In a 2013 study published in the journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, researchers found an increase in firearms victims between 2000 and 2011 coming in with — and dying of — more extensive wounds. In the same year, the Journal for Surgical Research published a 20-year retrospective of pediatric gunshot wounds, finding that in Miami-Dade County, the number of patients with multiple gunshot wounds increased. At a busy emergency department in Washington D.C., researchers writing in Archives of Surgery reported that between 1988 and 1990, the average number of gunshot entry wounds per patient brought in after a shooting rose from 1.44 to 2.04.

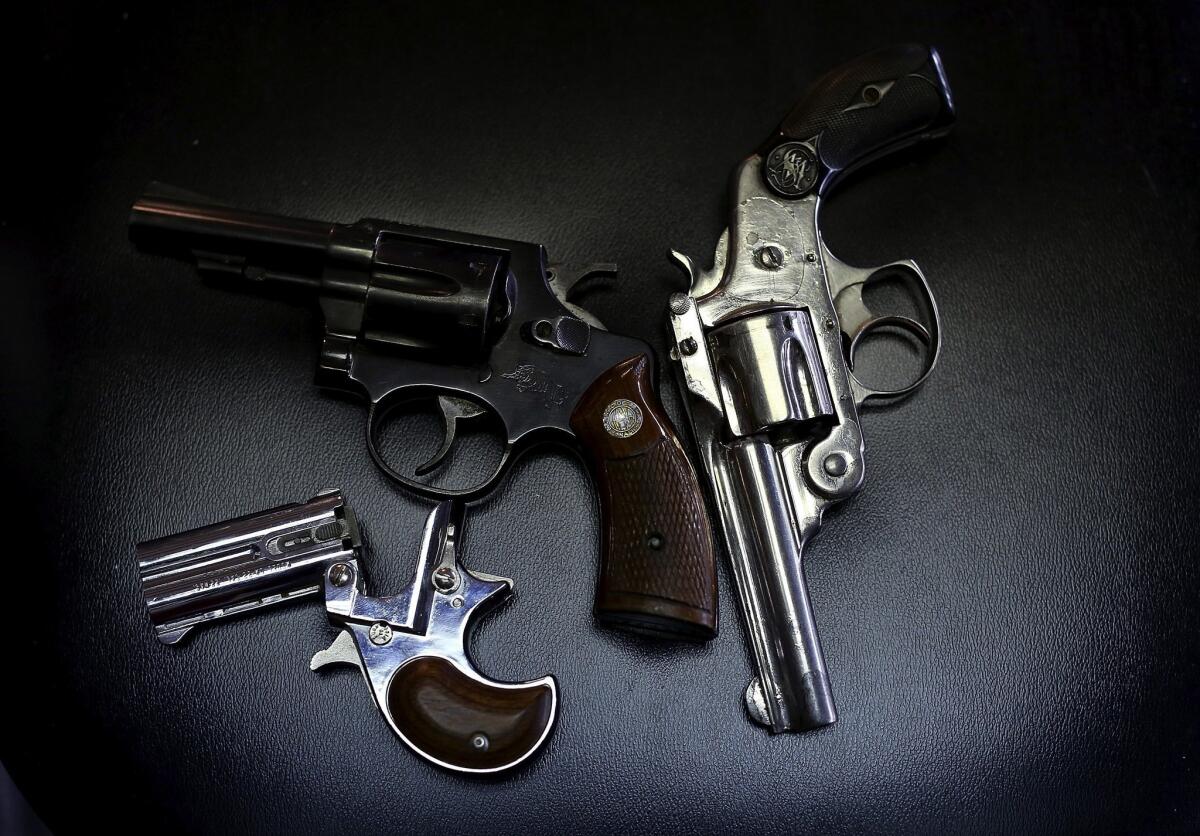

Dr. Garen Wintemute, a UC Davis injury-prevention researcher and emergency department physician, said the trend of more severely injured firearms victims “may reflect the increasing ammunition capacity of firearms used in violence.” Shooters may be more heavily armed, and armed with weapons that can wreak more destruction more efficiently.

As an example, military-style automatic weapons have proliferated among Americans since 2004, when Congress let a 20-year ban on civilian ownership of such guns expire. A database of mass shootings in the United States maintained by the publication Mother Jones shows that seven of the 10 U.S. mass shooting incidents with the highest number of casualties were carried out with military-style semiautomatic weapons. In addition to last weekend’s shooting in Orlando, those include the December 2015 San Bernardino attacks in which 14 were killed and 20 wounded; the 2012 movie theater rampage in Aurora, Colo. in which 12 were killed and 58 wounded; and the Newtown, Conn. shooting at an elementary school that claimed the lives of 28 people and wounded two more.

FOR THE RECORD

11:14 a.m.: An earlier version of this article referenced a database that shows seven of the 10 U.S. mass shooting incidents with the highest number of casualties were carried out with military-style automatic weapons. The reference should have been to military-style semiautomatic weapons.

Dr. Angela Sauaia, a co-author of the “Research Letter” in JAMA, said she could not explain why gunshot victims have been coming into Denver’s Anschutz Hospital Center more extensively hurt and more likely to die. She blamed Congress’s longstanding ban on federally funded firearms research for the dearth of explanatory data.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

“This research involved two years of very hard, unfunded work, to get this level of detail from one trauma center,” said Sauaia, a physician and epidemiologist at Denver Health Medical Center. “I should be able to tell you exactly” the role that different weapons play in firearms injuries, she added. But “congressional bans and disincentives for being a gun-related researcher preclude me from telling you what I wish I could. And the reason is not scientific: it’s political,” she added.

FOR THE RECORD

11:24 a.m.: An earlier version of this article stated that Dr. Angela Sauaia is a physician and epidemiologist at the University of Colorado’s school of public health. She is affiliated with the Denver Health Medical Center.

Sauaia said the new study offers some evidence that while injury-prevention research has made cars and other dangerous conveniences safer and trauma care more effective, guns and firearms-related injury has been an exception.

“Guns are not produced to make anything safe: they’re produced to do harm. In that sense, they’re doing what they were produced to do, and doing it very well,” said Sauaia.

Follow me on Twitter @LATMelissaHealy and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

In U.S., 38% of adults and 17% of kids are now obese, CDC study says

Five things pediatricians want dads to know about parenting

Light pollution prevents 1 in 3 Earthlings from seeing the Milky Way at night